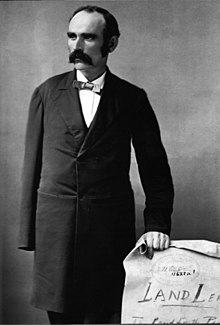

Charles Boycott

After retiring from the army, Boycott worked as a land agent for Lord Erne, a landowner in the Lough Mask area of County Mayo.

[1] In 1880, as part of its campaign for the Three Fs (fair rent, fixity of tenure, and free sale) and specifically in resistance to proposed evictions on the estate, local activists of the Irish National Land League encouraged Boycott's employees (including the seasonal workers required to harvest the crops on Lord Erne's estate) to withdraw their labour, and began a campaign of isolation against Boycott in the local community.

Newspapers sent correspondents to the West of Ireland to highlight what they viewed as the victimisation of a servant of a peer of the realm by Irish nationalists.

[8] McGregor Blacker agreed to sublet 2,000 acres (809 ha) of land belonging to the Irish Church Mission Society on Achill to Boycott, who moved there in 1854.

[8] Carr was also the local receiver of wrecks, which meant that he was entitled to collect the salvage from all shipwrecks in the area, and guard it until it was sold in a public auction.

[8] In 1873, Boycott moved to Lough Mask House, owned by Lord Erne, four miles (6 km) from Ballinrobe in County Mayo.

[10] The 3rd Earl of Erne was a wealthy Ulster landowner who lived at Crom Castle, a country house near Newtownbutler in the south-east of County Fermanagh.

[10] In his roles as farmer and agent, Boycott employed numerous local people as labourers, grooms, coachmen, and house-servants.

[10] Joyce Marlow wrote that Boycott had become set in his mode of thought, and that his twenty years on Achill had "...strengthened his innate belief in the divine right of the masters, and the tendency to behave as he saw fit, without regard to other people's point of view or feelings.

[14] Michael Davitt was the son of a small tenant farmer in County Mayo who became a journalist and joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

[15] The Land League was very active in the Lough Mask area, and one of the local leaders, Father John O'Malley, had been involved in the labourer's strike in August 1880.

[12] Three days after Parnell's speech in Ennis, a process server and seventeen members of the RIC began the attempt to serve Boycott's eviction notices.

[12] The women of the area descended on the process server and the constabulary, and began throwing stones, mud, and manure at them, succeeding in driving them away to seek refuge in Lough Mask House.

[12] News soon spread to nearby Ballinrobe, from where many people descended on Lough Mask House, where, according to journalist James Redpath, they advised Boycott's servants and labourers to leave his employment immediately.

[12] Martin Branigan, a labourer who subsequently sued Boycott for non-payment of wages, claimed he left because he was afraid of the people who came into the field where he was working.

[12] Boycott's young nephew volunteered to act as postman, but he was intercepted en route between Ballinrobe and Lough Mask, and told that he would be in danger if he continued.

On the 22nd September a process-server, escorted by a police force of seventeen men, retreated to my house for protection, followed by a howling mob of people, who yelled and hooted at the members of my family.

Lough Mask House, County Mayo, 14 OctoberAfter the publication of this letter, Bernard Becker, special correspondent of the Daily News, travelled to Ireland to cover Boycott's situation.

'"[19] Boycott had been advised to leave, but he told Becker that "I can hardly desert Lord Erne, and, moreover, my own property is sunk in this place.

[18] On 29 October, the Dublin Daily Express published a letter proposing a fund to finance a party of men to go to County Mayo to save Boycott's crops.

[20] In Belfast in early November 1880, The Boycott Relief Fund was established to arrange an armed expedition to Lough Mask.

[18] The committee had arranged with the Midland Great Western Railway for special trains to transport the expedition from Ulster to County Mayo.

[22] The expedition from South Ulster experienced hostile protests on their route through County Mayo, but there was no violence, and they harvested the crops without incident.

[20] In a letter requesting compensation to William Ewart Gladstone, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Boycott said that he had lost £6,000 of his investment in the estate.

[29] William Edward Forster argued that a Coercion Act—which would punish those who participated in events like those at Lough Mask, and would include the suspension of habeas corpus—should be introduced before any Land Act.

[30] The act set up the Irish Land Commission, a judicial body that would fix rents for a period of 15 years and guarantee fixity of tenure.

"Well," I said, "When the people ostracise a land-grabber we call it social excommunication, but we ought to have an entirely different word to signify ostracism applied to a landlord or land-agent like Boycott.

[18] In November 1880, an article in the Birmingham Daily Post referred to the word as a local term in connection to the boycotting of a Ballinrobe merchant.

[32] According to Gary Minda in his book, Boycott in America: How Imagination and Ideology Shape the Legal Mind, "Apparently there was no other word in the English language to describe this dispute.

This was the basis for the 1947 film Captain Boycott—directed by Frank Launder and starred Stewart Granger, Kathleen Ryan, Alastair Sim, and Cecil Parker as Charles Boycott.