Chattanooga campaign

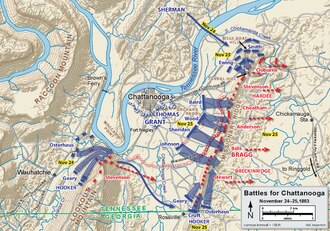

On November 24, Sherman's men crossed the Tennessee River in the morning and then advanced to occupy high ground at the northern end of Missionary Ridge in the afternoon.

Hoping to distract Bragg's attention, Grant ordered Thomas's army to advance in the center and take the Confederate positions at the base of Missionary Ridge.

The untenability of these newly captured entrenchments caused Thomas's men to surge to the top of Missionary Ridge and, with the help of Hooker's force advancing north from Rossville, routed the Confederate Army of Tennessee.

Bragg's defeat eliminated the last significant Confederate control of Tennessee and opened the door to an invasion of the Deep South, leading to Sherman's Atlanta campaign of 1864.

Chattanooga was a vital rail hub (with lines going north toward Nashville and Knoxville and south toward Atlanta), and an important manufacturing center for the production of iron and coal, located on the navigable Tennessee River.

The flanking option was deemed to be impracticable because Bragg's army was short on ammunition, they had no pontoons for river crossing, and Longstreet's corps from Virginia had arrived at Chickamauga without wagons.

Receiving intelligence that Rosecrans's men had only six days of rations, Bragg chose the siege option, while attempting to accumulate sufficient logistical capability to cross the Tennessee.

Only hours after the defeat at Chickamauga, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to Chattanooga with 20,000 men in two small corps from the Army of the Potomac in Virginia.

Even before the Union defeat, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had been ordered to send his available force to assist Rosecrans, and it departed under his chief subordinate, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, from Vicksburg, Mississippi.

If the Army of the Cumberland could seize Brown's Ferry and link up with Hooker's force arriving from Bridgeport, Alabama, through Lookout Valley, a reliable, efficient supply line—soon to become known as the "Cracker Line"—would be open.

Gen. William B. Hazen's) traveling stealthily downriver on pontoons and a raft at night to capture the gap and hills on the west bank of the Tennessee while a second brigade (Brig.

[19] Early on the morning of October 27, Hazen's men floated unnoticed past the Confederate position on Lookout Mountain, aided by low fog and no moonlight.

Gen. John W. Geary's division at Wauhatchie Station, a stop on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, to protect the line of communications to the south as well as the road west to Kelley's Ferry.

Responding to a suggestion from President Davis, Bragg announced in a council of war on November 3 that he was sending Longstreet and his two divisions into East Tennessee to deal with Burnside, replacing the Stevenson/Jackson force.

Campaign historian Steven E. Woodworth judged, however, that "even the flat loss of the number of good soldiers in Longstreet's divisions would have been a gain to the army in ridding it of their general's feuding and blundering.

Smith would assemble every available boat and pontoon to allow Sherman's corps to cross the Tennessee River near the mouth of the South Chickamauga Creek and attack Bragg's right flank on Missionary Ridge.

The plan also called for Hooker to assault and seize Lookout Mountain, Bragg's left flank, and continue on to Rossville, where he would be positioned to cut off a potential Confederate retreat to the south.

Jackson later wrote about the dissatisfaction of the commanders assigned to this area, "Indeed, it was agreed on all hands that the position was one extremely difficult to defense against a strong force of the enemy advancing under cover of a heavy fire.

[34] Dissatisfaction also prevailed in the Chattanooga Valley and on Missionary Ridge, where Breckinridge, commanding Bragg's center and right, had only 16,000 men to defend a line 5 miles long.

"[35] Bragg exacerbated the situation on November 22 by ordering Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne to withdraw his and Simon B. Buckner's divisions from the line and march to Chickamauga Station, for railroad transport to Knoxville, removing 11,000 more men from the defense of Chattanooga.

Wood's men assembled outside of their entrenchments and observed their objective approximately 2,000 yards to the east, a small knoll 100 feet high known as Orchard Knob (also known as Indian Hill).

Bragg began to reduce the strength on his left by withdrawing Maj. Gen. William H. T. Walker's division from the base of Lookout Mountain and placing them on the far right of Missionary Ridge, just south of Tunnel Hill.

After receiving assurances from Sherman that he could proceed with three divisions, Grant decided to revive the previously rejected plan for an attack on Lookout Mountain and reassigned Osterhaus to Hooker's command.

"[47] While the advance of Cruft and Osterhaus demonstrated at Lookout Creek, Geary crossed the stream unopposed further south and found that the defile between the mountain and the river had not been secured.

[57] As the morning progressed, Sherman launched multiple direct assaults against Cleburne's line on Tunnel Hill but, despite his significantly larger force, committed only four brigades to the attacks and made no headway.

Military historians Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones contend that the Battle of Missionary Ridge was "the war's most notable example of a frontal assault succeeding against intrenched defenders holding high ground.

By 4:30 p.m. the center of Bragg's line had broken completely and fled in panic, requiring the abandonment of Missionary Ridge and a headlong retreat eastward to South Chickamauga Creek.

Hooker decided to leave his guns and wagons behind so that all of his infantry could cross first, but his advance was delayed about three hours and he did not reach Rossville Gap until 3:30 p.m.[66] Breckinridge was absent while the Union attack wrecked his corps.

At 3:30 p.m., about the time Thomas launched his four-division attack on Missionary Ridge, Breckinridge visited Stewart's left flank brigade of Col. James T. Holtzclaw, whose commander pointed to the southwest where Hooker's men were busily bridging Chattanooga Creek.

[68] During the night, Bragg ordered his army to withdraw toward Chickamauga Station on the Western and Atlantic Railroad (currently the site of Lovell Air Field) and on November 26 began retreating toward Dalton, Georgia, in two columns taking two routes.