Chemical milling

[4] Most modern chemical milling methods involve alkaline etchants; these may have been used as early as the first century CE.

In 1782, the discovery was made by John Senebier that certain resins lost their solubility to turpentine when exposed to light; that is, they hardened.

This allowed the development of photochemical milling, where a liquid maskant is applied to the entire surface of a material, and the outline of the area to be masked created by exposing it to UV light.

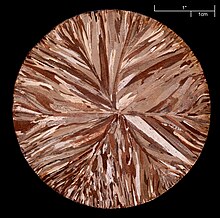

[7] Photo-chemical milling was extensively used in the development of photography methods, allowing light to create impressions on metal plates.

It is also used in the aerospace industry[10] to remove shallow layers of material from large aircraft components, missile skin panels, and extruded parts for airframes.

Chemical milling is normally performed in a series of five steps: cleaning, masking, scribing, etching, and demasking.

For most metals, this step can be performed by applying a solvent substance to the surface to be etched, washing away foreign contaminants.

It is common practice in modern industrial chemical etching facilities that the workpiece never be directly handled after this process, as oils from human skin could easily contaminate the surface.

The maskant must adhere to the surface of the material, and it must also be chemically inert enough with regard to the etchant to protect the workpiece.

For parts involving multiple stages of etching, complex templates using colour codes and similar devices may be used.

A de-oxidizing bath may also be required in the common case that the etching process left a film of oxide on the surface of the material.