Château de Chenonceau

[4] An architectural mixture of late Gothic and early Renaissance, Château de Chenonceau and its gardens are open to the public.

The work was overseen by his wife Katherine Briçonnet,[7] who delighted in hosting French nobility, including King Francis I on two occasions.

Diane de Poitiers was the unquestioned mistress of the castle, but ownership remained with the crown until 1555 when years of delicate legal manoeuvres finally yielded possession to her.

After King Henry II died in 1559, his strong-willed widow and regent Catherine de' Medici forced Diane to exchange it for the Château Chaumont.

In 1560, the first-ever fireworks display seen in France took place during the celebrations marking the ascension to the throne of Catherine's son Francis II.

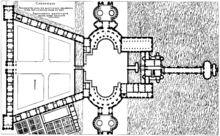

[10] Catherine considered an even greater expansion of the château, shown in an engraving published by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau in the second (1579) volume of his book Les plus excellents bastiments de France.

Louise spent the next 11 years, until her death in January 1601, wandering aimlessly along the château's corridors dressed in mourning clothes, amidst sombre black tapestries stitched with skulls and crossbones.

Henry IV obtained Chenonceau for his mistress Gabrielle d'Estrées by paying the debts of Catherine de' Medici, which had been inherited by Louise and were threatening to ruin her.

In return, Louise left the château to her niece Françoise de Lorraine, at that time six years old and betrothed to the four-year-old César, Duke of Vendôme, the natural son of Gabrielle d'Estrées and Henry IV.

"[16] The widowed Louise Dupin saved the château from destruction during the French Revolution, preserving it from being destroyed by the Revolutionaries because "it was essential to travel and commerce, being the only bridge across the river for many miles.

He almost completely renewed the interior and removed several of Catherine de' Medici's additions, including the rooms between the library and the chapel and her alterations to the north façade, among which were figures of Hercules, Pallas, Apollo, and Cybele that were moved to the park.

In 1951, the Menier family entrusted the château's restoration to Bernard Voisin, who brought the dilapidated structure and the gardens (ravaged in the Cher flood in 1940) back to a reflection of its former glory.