Chicano

[59] In Mexico, Chicano may still be associated with a Mexican American person of low importance, class, and poor morals (similar to the terms Cholo, Chulo and Majo), indicating a difference in cultural views.

"[78] Carlos Muñoz argues that the desire to separate themselves from Blackness and political struggle was rooted in an attempt to minimize "the existence of racism toward their own people, [believing] they could "deflect" anti-Mexican sentiment in society" through affiliating with the mainstream American culture.

[105] Alienation from public institutions made some Chicano youth susceptible to gang channels, who became drawn to their rigid hierarchical structure and assigned social roles in a world of government-sanctioned disorder.

[108] Chicano zoot suiters developed a unique cultural identity, as noted by Charles "Chaz" Bojórquez, "with their hair done in big pompadours, and "draped" in tailor-made suits, they were swinging to their own styles.

In Wretched, Fanon stated: "the past existence of an Aztec civilization does not change anything very much in the diet of the Mexican peasant today", elaborating that "this passionate search for a national culture which existed before the colonial era finds its legitimate reason in the anxiety shared by native intellectuals to shrink away from that of Western culture in which they all risk being swamped ... the native intellectuals, since they could not stand wonderstruck before the history of today's barbarity, decided to go back further and to delve deeper down; and, let us make no mistake, it was with the greatest delight that they discovered that there was nothing to be ashamed of in the past, but rather dignity, glory, and solemnity.

"[87] While acknowledging its romanticized and exclusionary foundations, Chicano scholars like Rafael Pérez-Torres state that Aztlán opened a subjectivity which stressed a connection to Indigenous peoples and cultures at a critical historical moment in which Mexican-Americans and Mexicans were "under pressure to assimilate particular standards—of beauty, of identity, of aspiration.

"[117] Roberto Cintli Rodríguez describes Chicanos as "de-Indigenized," which he remarks occurred "in part due to religious indoctrination and a violent uprooting from the land", detaching millions of people from maíz-based cultures throughout the greater Mesoamerican region.

[118][119] Rodríguez asks how and why "peoples who are clearly red or brown and undeniably Indigenous to this continent have allowed ourselves, historically, to be framed by bureaucrats and the courts, by politicians, scholars, and the media as alien, illegal, and less than human.

Historian Mario T. García reflects that "these anti-colonial and anti-Western movements for national liberation and self-awareness touched a historical nerve among Chicanos as they began to learn that they shared some similarities with these Third World struggles.

Specifically, I accuse the draft, the entire social, political, and economic system of the United States of America, of creating a funnel which shoots Mexican youth into Vietnam to be killed and to kill innocent men, women, and children...."[134] Rodolfo Corky Gonzales expressed a similar stance: "My feelings and emotions are aroused by the complete disregard of our present society for the rights, dignity, and lives of not only people of other nations but of our own unfortunate young men who die for an abstract cause in a war that cannot be honestly justified by any of our present leaders.

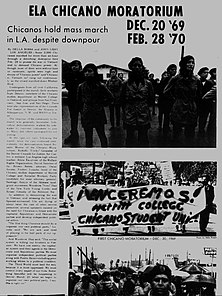

[139] In 1994, one of the largest demonstrations of Mexican Americans in the history of the United States occurred when 70,000 people, largely Chicanos and Latinos, marched in Los Angeles and other cities to protest Proposition 187, which aimed to cut educational and welfare benefits for undocumented immigrants.

The day prior, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover sent out a memo to law enforcement to place top priority on "political intelligence work to prevent the development of nationalist movements in minority communities".

Similarly, the General Brotherhood of Workers (CASA), important to the development of young Chicano intellectuals and activists, identified that, as "victims of oppression, Mexicanos could achieve liberation and self-determination only by engaging in a borderless struggle to defeat American international capitalism.

"[173][174] Anzaldúa writes that la frontera signals "the coming together of two self-consistent but habitually incompatible frames of reference [which] cause un choque, a cultural collision" because "the U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.

"[182] Sociologist José S. Plascencia-Castillo refers to the barrio as a panopticon that leads to intense self-regulation, as Cholo youth are both scrutinized by law enforcement to "stay in their side of town" and by the community who in some cases "call the police to have the youngsters removed from the premises".

Some youth feel they "can either comply with the demands of authority figures, and become obedient and compliant, and suffer the accompanying loss of identity and self-esteem, or, adopt a resistant stance and contest social invisibility to command respect in the public sphere.

According to a Pew Research Center report in 2015, "the primary role of Catholicism as a conduit to spirituality has declined and some Chicanos have changed their affiliation to other Christian religions and many more have stopped attending church altogether."

[209] Poet Alurista wrote that Chicano literature served an important role to push back against narratives by white Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture that sought to "keep Mexicans in their place.

[214] Characters in books such as Victuum (1976) by Isabella Ríos, The House on Mango Street (1983) by Sandra Cisneros, Loving in the War Years: lo que nunca pasó por sus labios (1983) by Cherríe Moraga, The Last of the Menu Girls (1986) by Denise Chávez, Margins (1992) by Terri de la Peña, and Gulf Dreams (1996) by Emma Pérez have also been read regarding how they intersect with themes of gender and sexuality.

[216] Other characters in the Chicano canon may also be read as queer, including the unnamed protagonist of Tomás Rivera's ...y no se lo tragó la tierra (1971), and "Antonio Márez" in Rudolfo Anaya's Bless Me, Ultima (1972).

Other notable musicians include Selena, who sang a mixture of Mexican, Tejano, and American popular music, and died in 1995 at the age of 23; Zack de la Rocha, social activist and lead vocalist of Rage Against the Machine; and Los Lonely Boys, a Texas-style country rock band.

Some of the most prominent Chicano artists include A.L.T., Lil Rob, Psycho Realm, Baby Bash, Serio, Proper Dos, Conejo,[231] A Lighter Shade of Brown, and Funky Aztecs.

Chicano rap artists with less mainstream exposure, yet with popular underground followings include Cali Life Style, Ese 40'z, Sleepy Loka, Ms. Sancha, Mac Rockelle, Sir Dyno.

Although Latin jazz is most popularly associated with artists from the Caribbean (particularly Cuba) and Brazil, young Mexican Americans have played a role in its development over the years, going back to the 1930s and early 1940s, the era of the zoot suit, when young Mexican-American musicians in Los Angeles and San Jose, such as Jenni Rivera, began to experiment with banda, a jazz-like fusion genre that has grown recently in popularity among Mexican Americans In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, a wave of Chicano pop music surfaced through innovative musicians Carlos Santana, Johnny Rodriguez, Ritchie Valens and Linda Ronstadt.

[235] El Teatro Campesino (The Farmworkers' Theater) was founded by Luis Valdez and Agustin Lira in 1965 as the cultural wing of the United Farm Workers (UFW) as a result of the Great Delano Grape Strike in 1965.

[236] In the 1990s, San Diego–based artist cooperative of David Avalos, Louis Hock, and Elizabeth Sisco used their National Endowment for the Arts $5,000 fellowship subversively, deciding to circulate money back to the community: "handing 10-dollar bills to undocumented workers to spend as they please."

[242][243] Prior to the introduction of spray cans, paint brushes were used by Chicano "shoeshine boys [who] marked their names on the walls with their daubers to stake out their spots on the sidewalk" in the early 20th century.

Marcos Sanchez-Tranquilino states that "rather than vandalism, the tagging of one's own murals points toward a complex sense of wall ownership and a social tension created by the uncomfortable yet approving attentions of official cultural authority.

"[251] Chicano poster art became prominent in the 1970s as a way to challenge political authority, with pieces such as Rupert García's Save Our Sister (1972), depicting Angela Davis, and Yolanda M. López's Who's the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?

[259] Manuel Paul's mural "Por Vida" (2015) at Galeria de la Raza in Mission District, San Francisco, which depicted queer and trans Chicanos, was targeted multiple times after its unveiling.