Chinese Buddhist canon

[8][9] The Chinese Buddhist Canon also contains many texts which were composed outside of the Indian subcontinent, including numerous texts composed in China, such as philosophical treatises, commentaries, histories, philological works, catalogs, biographies, geographies, travelogues, genealogies of famous monks, encyclopedias and dictionaries.

Most canons contained sūtras (discourses of the Buddha, 經 jīng), monastic rule texts (vinaya; 律 lǜ); and scholastic treatises (abhidharma; 阿毘曇 āpítán or 阿毗達磨 āpídámó).

[16][17] The first Chinese translations of Buddhist texts appeared during the later Han Dynasty during the reign of Emperor Ming (r. 58–75 ce).

[18] According to a Yuan dynasty catalogue (the Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu 至元法寶堪同總錄), there were about 194 known translators who worked on about 1,440 texts in 5,580 fascicles (juans).

[4][19] Jiang Wu writes that "for about a thousand years, translating, cataloging, and digesting these texts became a paramount task for Chinese Buddhists.

[22][23] Alongside the study, translation and copying of these numerous texts, Chinese Buddhists spent much time organizing, classifying and cataloguing them.

As such, according to Jiang Wu "for centuries, despite the fact that the canon has continued to grow, this core body has remained stable, without much alteration.

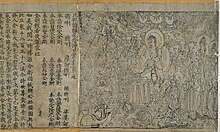

[25][17] Printing technology brought about a revolution in how the canon was reproduced, as well as in its layout, style and the various social elements associated with its production.

Sutra copying was also retained as an elite art form that made use of ink mixed with gold and silver powder and produced richly decorated manuscripts.

Some were built into the walls of a library, others were revolving repositories (lunzang 輪藏) that could be turned to easily access different texts.

[4] Many Chinese elites, including the imperial family and also even common people all aspired to support the copying and distribution of the Buddhist canon.

[5] Thus, one of the reasons for the copying of the Korean canon was the belief that the merit produced by this act could protect the nation from foreign invasion.

[33] Aside from copying and reading, another textual practice which was popular in Asia was the ceremony called "sunning the scriptures" (shaijing 曬經), which developed out of the need to regularly take out texts to prevent dampness.

[4] Another popular ritual was the ceremonial reading of the entire canon, a rite called "turning the scriptures" (zhuanjing 轉經).

[37] For example, in his Vimalakirti Sutra translation, the translator Zhi Qian sometimes follows the Sanskrit word order: 時 我 世尊 聞 是 法 默 而 止 不 能 加 報 (At that moment, I, Oh Lord, heard this law, [was] silent and stopped [speaking]; Skt.

The various canons also contain texts composed in China, Korea and Japan, including apocryphal sutras and Chinese Buddhist treatises.

[44] The blocks used to print the Kaibao Canon were lost in the fall of the Northern Song capital Kaifeng in 1127 and there are only about twelve fascicles worth of surviving material.

[44] After the Song government lost their war with the Jin dynasty and moved to the south in 1127, Buddhists in southern China worked to make new editions of the canon.

[45] The earliest edition of the Korean canon or Tripiṭaka Koreana (Koryŏ Taejanggyōng 高麗大藏經), also known as the Palman Daejanggyeong (80,000 Tripitaka), was first carved in the 11th century during the Goryeo period (918–1392).

A very hard and durable wood from the Betula schmidtii regal tree (known as Paktal in Korean), gathered on the islands off the coast, was used.

"[10] These woodblocks were kept in good condition until the modern era, and are seen as accurate sources for the classic Chinese Buddhist Canon.

[49] In the following eras, the canon was widely copied and maintained at various temple libraries and repositories, often with support from the government or important nobles.

This practice was called tendoku (転読) and is discussed by Nihon shoki 日本書紀, an important 8th century history book.

[51] The practice of copying Buddhist scriptures led to a new class of scribes, the standardization of textual production as well as the rise of manuscript art.

The Yongle canons however merged all these texts into a single collection of Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma (which sub-divisions for Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna).

[53] This canon was also influential outside of China, as it was re-printed in Japan under the auspices of Tetsugen Doko (1630–1682), a renowned master of the Ōbaku school.

The edition of the Buddhist canon, based on the Yongle, contains 1,675 titles in 7,240 fascicles and survives in a complete set of woodblocks (79,036 blocks).

It is the last canon printed in the traditional style (without any punctuation or modern typography) and the best preserved of the classic Chinese Tripitakas in China.

[75] The Mi Tripitaka (蕃大藏經) is a full Buddhist canon translated into the Tangut language from Chinese sources.

In 1965, Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism, BDK) was founded by Dr Yehan Numata with the express goal of translating the entire canon into English.