Kanji

[5] The significant use of Chinese characters in Japan first began to take hold around the 5th century AD and has since had a profound influence in shaping Japanese culture, language, literature, history, and records.

[6] According to the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki, a semi-legendary scholar called Wani was dispatched to Japan by the Kingdom of Baekje during the reign of Emperor Ōjin in the early fifth century, bringing with him knowledge of Confucianism and Chinese characters.

[6] For example, the diplomatic correspondence from King Bu of Wa to Emperor Shun of Liu Song in 478 AD has been praised for its skillful use of allusion.

[11] In ancient times, paper was so rare that people wrote kanji onto thin, rectangular strips of wood, called mokkan (木簡).

Around 650 AD, a writing system called man'yōgana (used in the ancient poetry anthology Man'yōshū) evolved that used a number of Chinese characters for their sound, rather than for their meaning.

Katakana (literally "partial kana", in reference to the practice of using a part of a kanji character) emerged via a parallel path: monastery students simplified man'yōgana to a single constituent element.

[citation needed] Since ancient times, there has been a strong opinion in Japan that kanji is the orthodox form of writing, but there were also people who argued against it.

Some of the new characters were previously jinmeiyō kanji; some are used to write prefecture names: 阪, 熊, 奈, 岡, 鹿, 梨, 阜, 埼, 茨, 栃 and 媛.

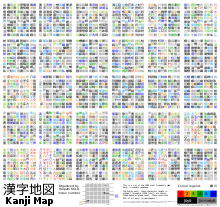

The Zhonghua Zihai, published in 1994 in China, contains about 85,000 characters, but the majority of them are not in common use in any country, and many are obscure variants or archaic forms.

However, some characters have only a single reading, such as kiku (菊, "chrysanthemum", an on-reading) or iwashi (鰯, "sardine", a kun-reading); kun-only are common for Japanese-coined kanji (kokuji).

There are many kanji compounds that use a mixture of on'yomi and kun'yomi, known as jūbako (重箱, multi-layered food box) or yutō (湯桶, hot liquid pail) words (depending on the order), which are themselves examples of this kind of compound (they are autological words): the first character of jūbako is read using on'yomi, the second kun'yomi (on-kun, Japanese: 重箱読み).

Gikun (義訓) and jukujikun (熟字訓) are readings of kanji combinations that have no direct correspondence to the characters' individual on'yomi or kun'yomi.

Aided with furigana, gikun could be used to convey complex literary or poetic effect (especially if the readings contradict the kanji), or clarification if the referent may not be obvious.

Sometimes, jukujikun can even have more kanji than there are syllables, examples being kera (啄木鳥, “woodpecker”), gumi (胡頽子, “silver berry, oleaster”),[31] and Hozumi (八月朔日, a surname).

For example, the word 相撲 (sumō, “sumo”) is originally from the verb 争う (sumau, “to vie, to compete”), while 今日 (kyō, “today”) is fusional (from older ke, “this” + fu, “day”).

The most common example of an inflectional jukujikun is the adjective 可愛い (kawai-i, “cute”), originally kawafayu-i; the word (可愛) is used in Chinese, but the corresponding on'yomi is not used in Japanese.

An extreme example is hototogisu (lesser cuckoo), which may be spelt in many ways, including 杜鵑, 時鳥, 子規, 不如帰, 霍公鳥, 蜀魂, 沓手鳥, 杜宇,田鵑, 沓直鳥, and 郭公—many of these variant spellings are particular to haiku poems.

In some rare cases, an individual kanji has a reading that is borrowed from a modern foreign language (gairaigo), though most often these words are written in katakana.

Though again, exceptions abound, for example, 情報 jōhō "information", 学校 gakkō "school", and 新幹線 shinkansen "bullet train" all follow this pattern.

北 "north" and 東 "east" use the kun'yomi kita and higashi, being stand-alone characters, but 北東 "northeast", as a compound, uses the on'yomi hokutō.

This is further complicated by the fact that many kanji have more than one on'yomi: 生 is read as sei in 先生 sensei "teacher" but as shō in 一生 isshō "one's whole life".

Examples include 手紙 tegami "letter", 日傘 higasa "parasol", and the famous 神風 kamikaze "divine wind".

Similarly, some on'yomi characters can also be used as words in isolation: 愛 ai "love", 禅 Zen, 点 ten "mark, dot".

Several famous place names, including those of Japan itself (日本 Nihon or sometimes Nippon), those of some cities such as Tokyo (東京 Tōkyō) and Kyoto (京都 Kyōto), and those of the main islands Honshu (本州 Honshū), Kyushu (九州 Kyūshū), Shikoku (四国 Shikoku), and Hokkaido (北海道 Hokkaidō) are read with on'yomi; however, the majority of Japanese place names are read with kun'yomi: 大阪 Ōsaka, 青森 Aomori, 箱根 Hakone.

The Osaka (大阪) and Kobe (神戸) baseball team, the Hanshin (阪神) Tigers, take their name from the on'yomi of the second kanji of Ōsaka and the first of Kōbe.

Although they are not typically considered jūbako or yutō, they often contain mixtures of kun'yomi, on'yomi and nanori, such as 大助 Daisuke [on-kun], 夏美 Natsumi [kun-on].

Parents can be quite creative, and rumours abound of children called 地球 Āsu ("Earth") and 天使 Enjeru ("Angel"); neither are common names, and have normal readings chikyū and tenshi respectively.

The corresponding phenomenon in Korea is called gukja (Korean: 국자; Hanja: 國字), a cognate name; there are however far fewer Korean-coined characters than Japanese-coined ones.

As a result, it is a common error in folk etymology to fail to recognize a phono-semantic compound, typically instead inventing a compound-indicative explanation.

Kanji, whose thousands of symbols defy ordering by conventions such as those used for the Latin script, are often collated using the traditional Chinese radical-and-stroke sorting method.