Lotus Sutra

According to the British Buddhologist Paul Williams, "For many Buddhists in East Asia since early times, the Lotus Sūtra contains the final teaching of Shakyamuni Buddha—complete and sufficient for salvation.

"[24] Although the term buddha-nature (buddhadhatu) is not mentioned in the Lotus Sūtra, Japanese scholars Hajime Nakamura and Akira Hirakawa suggest that the concept is implicitly present in the text.

The text states that the Buddha actually achieved Buddhahood innumerable eons ago, but remains in the world to help teach beings the Dharma time and again.

"[34] According to Stone, the sūtra has also been interpreted as promoting the idea that the Buddha's realm (buddhakṣetra) "is in some sense immanent in the present world, although radically different from our ordinary experience of being free from decay, danger and suffering."

[35] According to British writer Sangharakshita, the Lotus uses the entire cosmos for its stage, employs a multitude of mythological beings as actors and "speaks almost exclusively in the language of images.

During a gathering at Vulture Peak, Shakyamuni Buddha goes into a state of deep meditative absorption (samadhi), the earth shakes in six ways, and he brings forth a ray of light from the tuft of hair in between his eyebrows (ūrṇākośa) which illuminates thousands of buddha-fields in the east.

[67] Zimmermann noted the similarity with the nine parables in the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra that illustrate how the indwelling Buddha in sentient beings is hidden by negative mental states.

"[113] According to Peter Alan Roberts, the Lotus Sūtra may have had its origin among the Mahāsāṃghika school and may have been written in a middle Indic language (a prakrit) that was subsequently Sanskritized.

[114] The Lotus Sūtra was frequently cited in Indian scholarly treatises and compendiums and several authors of the Madhyamaka and the Yogacara school discussed and debated its doctrine of the One Vehicle.

[note 5] Lopez and Seishi Karashima outline these phases as follows:[120][121][122] Stephen F. Teiser and Jacqueline Stone opines that there is consensus about the stages of composition but not about the dating of these strata.

"[133] For Yogācāra scholars, this sutra was taught as an expedient means for the benefit of those persons who have entered the lesser śrāvaka vehicle but have the capacity to embrace the Mahāyāna.

[9] Based on his analysis of chapter 5, Zhanran would develop a new theory which held that even insentient beings such as rocks, trees and dust particles, possess buddha-nature.

By the 8th century, the sūtra was important enough that the emperor had established a network of nunneries, the so-called "Temples for the Eradication of Sins through the Lotus" (Hokke metsuzai no tera), in each province, as a way to protect the royal family and the state.

[171][172] Saichō attempted to create a great synthesis of the various Chinese Buddhist traditions in his new Tendai school (including esoteric, Pure Land, Zen and other elements), all which would be united under the Lotus One Vehicle doctrine.

[176] According to Jacqueline Stone, in Tendai esotericism, "the cosmic buddha is identified with the primordially enlightened Sakyamuni of the "Life Span" chapter, and his realm—that is, the entire universe—is conceived in mandalic terms as an ever-present, ongoing Lotus Sūtra assembly.

They focused instead on practices based on the simple recitation, listening or reading of the Lotus Sūtra in solitary places (bessho), something which did not require temples and ritual paraphernalia.

[181] The Japanese monk Nichiren (1222–1282) founded a new Buddhist school based on his belief that the Lotus Sūtra is "the Buddha's ultimate teaching",[183] and that the title is the essence of the sutra, "the seed of Buddhahood".

He therefore tasked himself and his followers with informing as many people as possible by refuting the provisional teachings and encouraging them to abandon their misconceptions of Buddhism through personal engagement (shakubuku) and directing them to the one vehicle of the Lotus.

He found this ideal in chapters 10–22 as the "third realm" of the Lotus Sutra (daisan hōmon) which emphasizes the need for a bodhisattva to endure the trials of life in the defiled sahā world.

[199][200] According to scholar Jacqueline Stone, Soka Gakkai generally follows an exclusivist approach to the Lotus Sūtra, believing that only Nichiren Buddhism can bring world peace.

"[34] In a similar fashion, Etai Yamada (1900–1999), the 253rd head priest of the Tendai denomination conducted ecumenical dialogues with religious leaders around the world based on his inclusive interpretation of the Lotus Sūtra, which culminated in a 1987 summit.

"[210] He also understood the Lotus Sūtra (as well as other Mahayana works) to be later, more "developed" texts than the "simple" earlier sutras which contained more historical content and less metaphysical ideas.

[218][219] After the Second World War, scholarly attention to the Lotus Sūtra was inspired by renewed interest in Japanese Buddhism as well as archeological research in Dunhuang in Gansu, China.

The term derived from the Sanskrit root dhr, related to dharani and could refer to the memorization and retention of the teaching as well as to the more abstract "apprehension" of the Dharma in meditative states of samadhi.

James Shields of Bucknell University remarked that, with regard to cultural influence, the Lotus Sūtra "plays a role equivalent to the Bible in Europe or the Qur’an in the Middle East.

[239][240][241] Wang argues that the explosion of art inspired by the Lotus Sūtra, starting from the 7th and 8th centuries in China, was a confluence of text and the topography of the Chinese medieval mind in which the latter dominated.

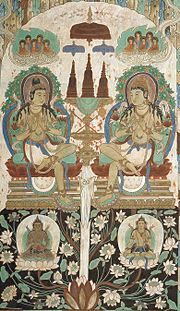

[243] In the fifth century, the scene of Shakyamuni and Prabhutaratna Buddhas seated together as depicted in the 11th chapter of the Lotus Sūtra became arguably the most popular theme in Chinese Buddhist art.

[251][252] According to Gene Reeves, "Japan's greatest twentieth-century storyteller and poet, Kenji Miyazawa, became devoted to the Lotus Sūtra, writing to his father on his own deathbed that all he ever wanted to do was share the teachings of this sutra with others."

[253] According to Jacqueline Stone and Stephen Teiser "the Noh drama and other forms of medieval Japanese literature interpreted Chapter 5, "Medicinal Herbs", as teaching the potential for buddhahood in grasses and trees (sōmoku jōbutsu).

The story of the Dragon King's daughter, who attained enlightenment in the 12th (Devadatta) chapter of the Lotus Sūtra, appears in the Complete Tale of Avalokiteśvara and the Southern Seas and the Precious Scroll of Sudhana and Longnü folkstories.