Traditional Chinese medicine

[1][2] Medicine in traditional China encompassed a range of sometimes competing health and healing practices, folk beliefs, literati theory and Confucian philosophy, herbal remedies, food, diet, exercise, medical specializations, and schools of thought.

"[19] TJ Hinrichs observes that people in modern Western societies divide healing practices into biomedicine for the body, psychology for the mind, and religion for the spirit, but these distinctions are inadequate to describe medical concepts among Chinese historically and to a considerable degree today.

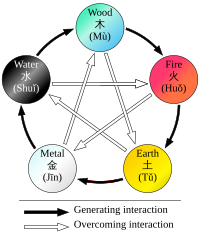

[20] The medical anthropologist Charles Leslie writes that Chinese, Greco-Arabic, and Indian traditional medicines were all grounded in systems of correspondence that aligned the organization of society, the universe, and the human body and other forms of life into an "all-embracing order of things".

They provided, Leslie continued, a "comprehensive way of conceiving patterns that ran through all of nature," and they "served as a classificatory and mnemonic device to observe health problems and to reflect upon, store, and recover empirical knowledge," but they were also "subject to stultifying theoretical elaboration, self-deception, and dogmatism.

[29] Unlike earlier texts like Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments, which was excavated in the 1970s from the Mawangdui tomb that had been sealed in 168 BCE, the Inner Canon rejected the influence of spirits and the use of magic.

Having gone through numerous changes over time, the formulary now circulates as two distinct books: the Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and the Essential Prescriptions of the Golden Casket, which were edited separately in the eleventh century, under the Song dynasty.

[33] Nanjing or "Classic of Difficult Issues", originally called "The Yellow Emperor Eighty-one Nan Jing", ascribed to Bian Que in the eastern Han dynasty.

[37] Prominent medical scholars of the post-Han period included Tao Hongjing (456–536), Sun Simiao of the Sui and Tang dynasties, Zhang Jiegu (c. 1151–1234), and Li Shizhen (1518–1593).

A majority of Chinese medical history written after the classical canons comes in the form of primary source case studies where academic physicians record the illness of a particular person and the healing techniques used, as well as their effectiveness.

[54] Historians have noted that Chinese scholars wrote these studies instead of "books of prescriptions or advice manuals;" in their historical and environmental understanding, no two illnesses were alike so the healing strategies of the practitioner was unique every time to the specific diagnosis of the patient.

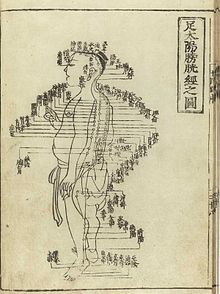

[2] One of the basic tenets of TCM is that the body's qi (sometimes translated as vital energy) is circulating through channels called meridians having branches connected to bodily organs and functions.

Concepts of the body and of disease used in TCM reflect its ancient origins and its emphasis on dynamic processes over material structure, similar to Classical humoral theory.

The former is called yingqi (营气; 營氣; yíngqì); its function is to complement xuè and its nature has a strong yin aspect (although qi in general is considered to be yang).

[96] The zangfu (脏腑; 臟腑; zàngfǔ) are the collective name of eleven entities (similar to organs) that constitute the centre piece of TCM's systematization of bodily functions.

[102] The meridians (经络, jīng-luò) are believed to be channels running from the zàng-fǔ in the interior (里, lǐ) of the body to the limbs and joints ("the surface" [表, biaǒ]), transporting qi and xuĕ.

[113] Yin and yang concepts were applied to the feminine and masculine aspects of all bodies, implying that the differences between men and women begin at the level of this energy flow.

According to Bequeathed Writings of Master Chu the male's yang pulse movement follows an ascending path in "compliance [with cosmic direction] so that the cycle of circulation in the body and the Vital Gate are felt...The female's yin pulse movement follows a defending path against the direction of cosmic influences, so that the nadir and the Gate of Life are felt at the inch position of the left hand".

[114] In sum, classical medicine marked yin and yang as high and low on bodies which in turn would be labeled normal or abnormal and gendered either male or female.

According to Charlotte Furth, "a pregnancy (in the seventeenth century) as a known bodily experience emerged [...] out of the liminality of menstrual irregularity, as uneasy digestion, and a sense of fullness".

The seventh-century scholar Sun Simiao is often quoted: "those who have prescriptions for women's distinctiveness take their differences of pregnancy, childbirth and [internal] bursting injuries as their basis.

[121] There are three fundamental categories of disease causes (三因; sān yīn) recognized:[76] In TCM, there are five major diagnostic methods: inspection, auscultation, olfaction, inquiry, and palpation.

[191] Tu says she was influenced by a traditional Chinese herbal medicine source, The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency Treatments, written in 340 by Ge Hong, which states that this herb should be steeped in cold water.

[193][194] Also in the 1970s Chinese researcher Zhang TingDong and colleagues investigated the potential use of the traditionally used substance arsenic trioxide to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).

[32] Traditional herbal medicines can contain extremely toxic chemicals and heavy metals, and naturally occurring toxins, which can cause illness, exacerbate pre-existing poor health or result in death.

[204] Traditional herbal medicines are sometimes contaminated with toxic heavy metals, including lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium, which inflict serious health risks to consumers.

[214] A 2013 review suggested that although the antimalarial herb Artemisia annua may not cause hepatotoxicity, haematotoxicity, or hyperlipidemia, it should be used cautiously during pregnancy due to a potential risk of embryotoxicity at a high dose.

[67] For example, the misuse of the dietary supplement Ephedra (containing ephedrine) can lead to adverse events including gastrointestinal problems as well as sudden death from cardiomyopathy.

Qìgōng (气功; 氣功) is a TCM system of exercise and meditation that combines regulated breathing, slow movement, and focused awareness, purportedly to cultivate and balance qi.

[253] During British rule, Chinese medicine practitioners in Hong Kong were not recognized as "medical doctors", which means they could not issue prescription drugs, give injections, etc.

This inclusion granted qualified and professionally registered acupuncturists to provide subsidised care and treatment to citizens, residents, and temporary visitors for work or sports related injuries that occurred within and upon the land of New Zealand.