Placenta

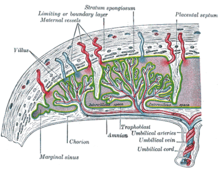

[1] The placenta connects to the fetus via the umbilical cord, and on the opposite aspect to the maternal uterus in a species-dependent manner.

Placentas are a defining characteristic of placental mammals, but are also found in marsupials and some non-mammals with varying levels of development.

The protein syncytin, found in the outer barrier of the placenta (the syncytiotrophoblast) between mother and fetus, has a certain RNA signature in its genome that has led to the hypothesis that it originated from an ancient retrovirus: essentially a virus that helped pave the transition from egg-laying to live-birth.

[9] The mammalian placenta evolved more than 100 million years ago and was a critical factor in the explosive diversification of placental mammals.

Vessels branch out over the surface of the placenta and further divide to form a network covered by a thin layer of cells.

Placental expulsion can be managed actively, for example by giving oxytocin via intramuscular injection followed by cord traction to assist in delivering the placenta.

Blood loss and the risk of postpartum bleeding may be reduced in women offered active management of the third stage of labour, however there may be adverse effects and more research is necessary.

[25] The placenta is traditionally thought to be sterile, but recent research suggests that a resident, non-pathogenic, and diverse population of microorganisms may be present in healthy tissue.

[31] Adverse pregnancy situations, such as those involving maternal diabetes or obesity, can increase or decrease levels of nutrient transporters in the placenta potentially resulting in overgrowth or restricted growth of the fetus.

[32] Waste products excreted from the fetus such as urea, uric acid, and creatinine are transferred to the maternal blood by diffusion across the placenta.

[33][35][36][37] Beginning as early as 13 weeks of gestation, and increasing linearly, with the largest transfer occurring in the third trimester, IgG antibodies can pass through the human placenta, providing protection to the fetus in utero.

IgM antibodies, because of their larger size, cannot cross the placenta,[40] one reason why infections acquired during pregnancy can be particularly hazardous for the fetus.

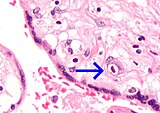

[46] The trophoblast is the outer layer of cells of the blastocyst (see day 9 in Figure, above, showing the initial stages of human embryogenesis).

Placental trophoblast cells have a unique genome-wide DNA methylation pattern determined by de novo methyltransferases during embryogenesis.

[47] This methylation pattern is principally required to regulate placental development and function, which in turn is critical for embryo survival.

[citation needed] The placenta often plays an important role in various cultures, with many societies conducting rituals regarding its disposal.

The Māori of New Zealand traditionally bury the placenta from a newborn child to emphasize the relationship between humans and the earth.

[50] Likewise, the Navajo bury the placenta and umbilical cord at a specially chosen site,[51] particularly if the baby dies during birth.

[52] In Cambodia and Costa Rica, burial of the placenta is believed to protect and ensure the health of the baby and the mother.

In Turkey, the proper disposal of the placenta and umbilical cord is believed to promote devoutness in the child later in life.

[53][55] Native Hawaiians believe that the placenta is a part of the baby, and traditionally plant it with a tree that can then grow alongside the child.

[49] Various cultures in Indonesia, such as Javanese and Malay, believe that the placenta has a spirit and needs to be buried outside the family house.