Chinese Exclusion Act

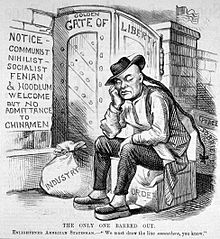

These laws attempted to stop all Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years, with exceptions for diplomats, teachers, students, merchants, and travelers.

While many of these legislative efforts were quickly overturned by the State Supreme Court,[13] many more anti-Chinese laws continued to be passed in both California and nationally.

[19] Before 1876, Californian legislators had made various attempts to restrict Chinese immigration by targeting Chinese businesses, living spaces[citation needed] and the ships immigrants arrived on by way of ordinances and resultant fines, but such legislation was deemed unconstitutional through its violation of either the Burlingame Treaty, the Fourteenth Amendment, or the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

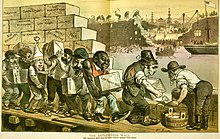

Furthering these measures was the sending of a delegation by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to cities in the east to express anti-Chinese sentiment to crowds (and later newspapers).

[19] It is for these reasons then that the election year of 1876 was instrumental in changing the question of Chinese immigration from a state to a national question; The competitive political atmosphere allowed a calculated political attempt to nationalize California's Immigration grievances,[2] as such leaders across the country (whose concerns with the benefits or ill of Chinese-labour were second to winning votes) were compelled to advocacy for anti-Chinese sentiment.

[2] This perfectly reflected the overall feeling of many Americans at the time, and how public officials were partly responsible in making this situation seem even more serious than it actually was.

[28] The bill passed the Senate and House by overwhelming margins, but this as well was vetoed by President Chester A. Arthur, who concluded the 20-year ban to be a breach of the renegotiated treaty of 1880.

[28][29] After the act was passed, most Chinese workers were faced with a dilemma: stay in the United States alone or return to China to reunite with their families.

[31][6] Although widespread dislike for the Chinese persisted well after the law itself was passed, of note is that some capitalists and entrepreneurs resisted their exclusion because they accepted lower wages.

This extension was then made permanent in 1902 which led to every Chinese American ordered to gain a certificate of residence from the US government or face deportation.

Diplomatic officials and other officers on business, along with their house servants, for the Chinese government were also allowed entry as long as they had the proper certification verifying their credentials.

[34] Amendments made in 1884 tightened the provisions that allowed previous immigrants to leave and return and clarified that the law applied to ethnic Chinese regardless of their country of origin.

[30] Constitutionality of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Scott Act was upheld by the Supreme Court in Chae Chan Ping v. United States (1889); the Supreme Court declared that "the power of exclusion of foreigners [is] an incident of sovereignty belonging to the government of the United States as a part of those sovereign powers delegated by the constitution".

In United States v. Ju Toy (1905), the US Supreme Court reaffirmed that the port inspectors and the Secretary of Commerce had final authority on who could be admitted.

In the 1900s the Office of the Superintendent of Immigration was established by the Department of the Treasury and given responsibility for implementing federal regulations mandated by the Chinese exclusion laws.

[53] The American Christian George F. Pentecost spoke out against Western imperialism in China, saying:[54] I personally feel convinced that it would be a good thing for America if the embargo on Chinese immigration were removed.

[55] The massacre was named for the town where it took place, Rock Springs, Wyoming, in Sweetwater County, where white miners were jealous of the Chinese for their employment.

The actual events are still unclear due to unreliable law enforcement at the time, biased news reporting, and lack of serious official investigations.

[59] Men and women would walk across the American border intending to be arrested, to demand to go to court and claim they were born in America through providing a witness of their birth.

[66] Furthermore, when the US extended the law to Hawaii and the Philippines in 1902, this was greatly objected by the Chinese government and people, who viewed America as a bullish and imperial power who undermined China.

As such, unique categories were created in the act to prevent their entry, so that the main way they immigrated was through marrying Chinese or native men.

International education programs allowed students to learn from the examples provided at elite universities and to bring their newfound skill sets back to their home countries.

[48] Laws and regulations that stemmed from the act made for less than ideal situations for Chinese students, leading to criticisms of American society.

In this way, it facilitated further restriction by both being the model by which future groups could be radicalized as unassimilable aliens, and by also marking a moment where such discrimination could be justifiable.

Public perceptions of many immigrant groups such as Southern and Eastern Europeans in the late 19th and early 20th century had become one of "undesirability" when compared to those with Anglo-Saxon heritage, this was due largely to popular nativity attitudes and accepted racialism.

[2][47] In this way, the restriction of these groups by 1924 compared to their Northwestern "desirable" counterparts could be seen to be carrying on the discrimination by perceived racial inferiority of immigrants that started with the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Magnuson Act permitted Chinese nationals already residing in the country to become naturalized citizens and stop hiding from the threat of deportation.

Currently (as of December 2024), although all its constituent sections have long been repealed, Chapter 7 of Title 8 of the United States Code is headed "Exclusion of Chinese".

683, a resolution introduced by Congresswoman Judy Chu which formally expresses the regret of the House of Representatives for the Chinese Exclusion Act.

In times of societal crisis—whether perceived or real—patterns of retractability of American identities have erupted to the forefront of America's political landscape, often generating institutional and civil society backlash against workers from other nations, a pattern documented by Fong's research into how crises drastically alter social relationships.