Chinese herbology

A Nature editorial described TCM as "fraught with pseudoscience", and said that the most obvious reason why it has not delivered many cures is that the majority of its treatments have no logical mechanism of action.

[1] The term herbology is misleading in the sense that, while plant elements are by far the most commonly used substances, animal, human, and mineral products are also used, some of which are poisonous.

His Shénnóng Běn Cǎo Jīng (神農本草經, Shennong's Materia Medica) is considered as the oldest book on Chinese herbal medicine.

It classifies 365 species of roots, grass, woods, furs, animals and stones into three categories of herbal medicine:[8] The original text of Shennong's Materia Medica has been lost; however, there are extant translations.

[11] This formulary was also the earliest Chinese medical text to group symptoms into clinically useful "patterns" (zheng, 證) that could serve as targets for therapy.

Having gone through numerous changes over time, it now circulates as two distinct books: the Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and the Essential Prescriptions of the Golden Casket, which were edited separately in the eleventh century, under the Song dynasty.

Arguably the most important of these later works is the Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu, 本草綱目) compiled during the Ming dynasty by Li Shizhen, which is still used today for consultation and reference.

[17] Furthermore, the classic materia medica Bencao Gangmu describes the use of 35 traditional Chinese medicines derived from the human body, including bones, fingernail, hairs, dandruff, earwax, impurities on the teeth, feces, urine, sweat, and organs, but most are no longer in use.

This dough is then machine cut into tiny pieces, a small amount of excipients are added for a smooth and consistent exterior, and they are spun into pills.

In China, all Chinese patent medicines of the same name will have the same proportions of ingredients, and manufactured in accordance with the PRC Pharmacopoeia, which is mandated by law.

[24][better source needed] There are several different methods to classify traditional Chinese medicinals: The Four Natures are: hot (熱; 热), warm (溫; 温), cool (涼), cold (寒) or neutral (平).

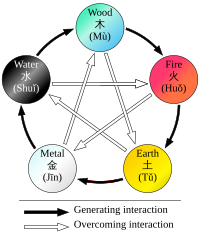

[25] Each of the Five Flavors corresponds to one of the zàng organs, which in turn corresponds to one of the Five Phases:[26] A flavor implies certain properties and presumed therapeutic "actions" of a substance: saltiness "drains downward and softens hard masses";[25] sweetness is "supplementing, harmonizing, and moistening";[25] pungent substances are thought to induce sweat and act on qi and blood; sourness tends to be astringent (澀; 涩) in nature; bitterness "drains heat, purges the bowels, and eliminates dampness".

Examples of such names include Niu Xi (Radix cyathulae seu achyranthis), 'cow's knees,' which has big joints that might look like cow knees; Bai Mu Er (Fructificatio tremellae fuciformis), 'white wood ear', which is white and resembles an ear; Gou Ji (Rhizoma cibotii), 'dog spine,' which resembles the spine of a dog.

Huang Bai (Cortex Phellodendri) means 'yellow fir," and Jin Yin Hua (Flos Lonicerae) has the label 'golden silver flower.

[31] Since TCM has become more popular in the Western world, there are increasing concerns about the potential toxicity of many traditional Chinese medicinals including plants, animal parts and minerals.

Edzard Ernst "concluded that adverse effects of herbal medicines are an important albeit neglected subject in dermatology, which deserves further systematic investigation.

"[37] Research suggests that the toxic heavy metals and undeclared drugs found in Chinese herbal medicines might be a serious health issue.

[38] Substances known to be potentially dangerous include aconite,[32] secretions from the Asiatic toad,[39] powdered centipede,[40] the Chinese beetle (Mylabris phalerata, Ban mao),[41] and certain fungi.

[6][clarification needed] Contrary to popular belief, Ganoderma lucidum mushroom extract, as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy, appears to have the potential for toxicity.

[43] Also, adulteration of some herbal medicine preparations with conventional drugs which may cause serious adverse effects, such as corticosteroids, phenylbutazone, phenytoin, and glibenclamide, has been reported.

[6] For example, the misuse of the dietary supplement Ephedra (containing ephedrine) can lead to adverse events including gastrointestinal problems as well as sudden death from cardiomyopathy.

[4] A 2016 Cochrane review found "insufficient evidence that Chinese Herbal Medicines were any more or less effective than placebo or hormonal therapy" for the relief of menopause related symptoms.

[49] A 2010 Cochrane review found there is not enough robust evidence to support the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine herbs to stop the bleeding from haemorrhoids.

[51] A 2012 Cochrane review found weak evidence suggesting that some Chinese medicinal herbs have a similar effect at preventing and treating influenza as antiviral medication.

[52] Due to the poor quality of these medical studies, there is insufficient evidence to support or dismiss the use of Chinese medicinal herbs for the treatment of influenza.

[52] There is a need for larger and higher quality randomized clinical trials to determine how effective Chinese herbal medicine is for treating people with influenza.

Modern Materia Medicas such as Bensky, Clavey and Stoger's comprehensive Chinese herbal text discuss substances derived from endangered species in an appendix, emphasizing alternatives.

Increased international attention has mostly stopped the use of bile outside of China; gallbladders from butchered cattle (牛胆; 牛膽; niú dǎn) are recommended as a substitute for this ingredient.

Some of the most commonly used herbs are Ginseng (人参; 人參; rénshēn), wolfberry (枸杞子; gǒuqǐzǐ), dong quai (Angelica sinensis, 当归; 當歸; dāngguī), astragalus (黄耆; 黃耆; huángqí), atractylodes (白术; 白朮; báizhú), bupleurum (柴胡; cháihú), cinnamon (cinnamon twigs (桂枝; guìzhī) and cinnamon bark (肉桂; ròuguì)), coptis (黄连; 黃連; huánglián), ginger (姜; 薑; jiāng), hoelen (茯苓; fúlíng), licorice (甘草; gāncǎo), ephedra sinica (麻黄; 麻黃; máhuáng), peony (white: 白芍; báisháo and reddish: 赤芍; chìsháo), rehmannia (地黄; 地黃; dìhuáng), rhubarb (大黄; 大黃; dàhuáng), and salvia (丹参; 丹參; dānshēn).

[100] Within TCM formulas, there are also strict rules about which herbs pair well together (Dui Yao), and which are either contradictory, incompatible, or may cause a reaction amongst themselves, or with Western Medicine Drugs.