Chinese folk religion

[7] Feng shui, acupuncture, and traditional Chinese medicine reflect this world view, since features of the landscape as well as organs of the body are in correlation with the five powers and yin and yang.

[16] Contemporary academic study of traditional cults and the creation of a government agency that gave legal status to this religion [17] have created proposals to formalise names and deal more clearly with folk religious sects and help conceptualise research and administration.

[23] During the late Qing dynasty, scholars Yao Wendong and Chen Jialin used the term shenjiao not referring to Shinto as a definite religious system, but to local shin beliefs in Japan.

Many scholars, following the lead of sociologist C. K. Yang, see the ancient Chinese religion deeply embedded in family and civic life, rather than expressed in a separate organizational structure like a "church", as in the West.

[39] Neither initiation rituals nor official membership into a church organization separate from one person's native identity are mandatory in order to be involved in religious activities.

[48] From the 3rd century on by the Northern Wei, accompanying the spread of Buddhism in China, strong influences from the Indian subcontinent penetrated the ancient Chinese indigenous religion.

The Nationalist government of the Republic of China intensified the suppression of the ancient Chinese religion with the 1928 "Standards for retaining or abolishing gods and shrines"; the policy attempted to abolish the cults of all gods with the exception of ancient great human heroes and sages such as the Yellow Emperor, Yu the Great, Guan Yu, Sun Tzu, Nuwa, Mazu, Guanyin, Xuanzang, Kūkai, Buddha, Budai, Bodhidharma, Lao Tzu, and Confucius.

[61] Ancient Chinese religion draws from a vast heritage of sacred books, which according to the general worldview treat cosmology, history and mythology, mysticism and philosophy, as aspects of the same thing.

[95] As forces of growth the gods are regarded as yang, opposed to a yin class of entities called gui (鬼; guǐ; cognate of 歸; guī 'return', 'contraction'),[93] chaotic beings.

[101] Hun (mind) is the soul (shen) that gives a form to the vital breath (qi) of humans, and it develops through the po, stretching and moving intelligently in order to grasp things.

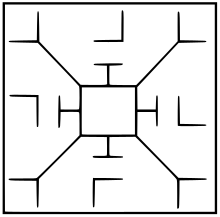

[108] Humans are considered one of the three aspects of a trinity (Chinese: 三才 Sāncái, "Three Powers"),[109] the three foundations of all being; specifically, men are the medium between Heaven that engenders order and forms and Earth which receives and nourishes them.

[109][note 6] The Chinese traditional concept of bao ying ("reciprocity", "retribution" or "judgement"), is inscribed in the cosmological view of an ordered world, in which all manifestations of being have an allotted span (shu) and destiny,[111] and are rewarded according to the moral-cosmic quality of their actions.

[113] The cosmic significance of bao ying is better understood by exploring other two traditional concepts of fate and meaning:[10] Ming yun and yuan fen are linked, because what appears on the surface to be chance (either positive or negative), is part of the deeper rhythm that shapes personal life based on how destiny is directed.

[112] Recognising this connection has the result of making a person responsible for his or her actions:[113] doing good for others spiritually improves oneself and contributes to the harmony between men and environmental gods and thus to the wealth of a human community.

[115] These three themes of the Chinese tradition—moral reciprocity, personal destiny, fateful coincidence—are completed by a fourth notion:[116] As part of the trinity of being (the Three Powers), humans are not totally submissive to spiritual force.

[120] She mentions the example of a Chenghuang Temple in Yulin, Shaanxi, that was turned into a granary during the Cultural Revolution; it was restored to its original function in the 1980s after seeds stored within were always found to have rotted.

[126] These societies organise gatherings and festivals (miaohui Chinese: 廟會) participated by members of the whole village or larger community on the occasions of what are believed to be the birthdays of the gods or other events,[59] or to seek protection from droughts, epidemics, and other disasters.

[59] Special devotional currents within this framework can be identified by specific names such as Mazuism (Chinese: 媽祖教 Māzǔjiào),[127] Wang Ye worship, or the cult of the Silkworm Mother.

[132] Kinship associations or churches (zōngzú xiéhuì Chinese: 宗族協會), congregating people with the same surname and belonging to the same kin, are the social expression of this religion: these lineage societies build temples where the deified ancestors of a certain group (for example the Chens or the Lins) are enshrined and worshiped.

[134] Scholar K. S. Yang has explored the ethno-political dynamism of this form of religion, through which people who become distinguished for their value and virtue are considered immortal and receive posthumous divine titles, and are believed to protect their descendants, inspiring a mythological lore for the collective memory of a family or kin.

Taoists of the Zhengyi school, who are called sǎnjū dàoshi (Chinese: 散居道士) or huǒjū dàoshi (Chinese: 火居道士), respectively meaning "scattered daoshi" and "daoshi living at home (hearth)", because they can get married and perform the profession of priests as a part-time occupation, may perform rituals of offering (jiao), thanks-giving, propitiation, exorcism and rites of passage for local communities' temples and private homes.

[149] China has a long history of sect traditions characterised by a soteriological and eschatological character, often called "salvationist religions" (Chinese: 救度宗教 jiùdù zōngjiào).

[155] They are characterised by several elements, including egalitarianism; foundation by a charismatic figure; direct divine revelation; a millenarian eschatology and voluntary path of salvation; an embodied experience of the numinous through healing and cultivation; and an expansive orientation through good deeds, evangelism and philanthropy.

It regards the other Luanism, a cluster of churches which focus on social morality through refined Confucian ritual to worship the gods, as the "Way of Later Heaven" (Chinese: 後天道 Hòutiāndào), that is the cosmological state of created things.

[87] The gods (shen Chinese: 神; "growth", "beings that give birth"[190]) are interwoven energies or principles that generate phenomena which reveal or reproduce the way of Heaven, that is to say the order (li) of the Greatnine(Tian).

[110] Among those worshipped as immortal heroes (xian, exalted beings) are historical individuals distinguished for their worth or bravery, those who taught crafts to others and formed societies establishing the order of Heaven, ancestors or progenitors (zu Chinese: 祖), and the creators of a spiritual tradition.

[218] A gathering or event may be encompassed with all of these aspects; in general, the commitment (belief) and the process or rite (practice) together form the internal and external dimensions of Chinese religious life.

[221] Virtue is believed to accumulate in one's heart, which is seen as energetic centre of the human body (zai jun xin zuo tian fu Chinese: 在君心作福田).

Classical Chinese has characters for different types of sacrifice, probably the oldest way to communicate with divine forces, today generally encompassed by the definition jìsì (祭祀).

In contrast to Weberian predictions, these phenomena suggest that drastic economic development in the Pearl River Delta may not lead to total disenchantment with beliefs concerning magic in the cosmos.

"Tian is dian Chinese : 顛 ('top'), the highest and unexceeded. It derives from the characters yi Chinese : 一 , 'one', and da Chinese : 大 , 'big'." [ note 1 ]