Oriented matroid

An oriented matroid is a mathematical structure that abstracts the properties of directed graphs, vector arrangements over ordered fields, and hyperplane arrangements over ordered fields.

[1] In comparison, an ordinary (i.e., non-oriented) matroid abstracts the dependence properties that are common both to graphs, which are not necessarily directed, and to arrangements of vectors over fields, which are not necessarily ordered.

Matroids are often useful in areas such as dimension theory and algorithms.

[5] Subsequently R.T. Rockefellar (1969) suggested the problem of generalizing Minty's concept to real vector spaces.

His proposal helped lead to the development of the general theory.

This will make sense as a "direction" only when we consider orientations of larger structures.

Then the sign of each element will encode its direction relative to this orientation.

Like ordinary matroids, several equivalent systems of axioms exist.

(Such structures that possess multiple equivalent axiomatizations are called cryptomorphic.)

that satisfies the following axioms: The term chirotope is derived from the mathematical notion of chirality, which is a concept abstracted from chemistry, where it is used to distinguish molecules that have the same structure except for a reflection.

In this sense, (B0) is the nonempty axiom for bases and (B2) is the basis exchange property.

Oriented matroids are often introduced (e.g., Bachem and Kern) as an abstraction for directed graphs or systems of linear inequalities.

and those edges whose orientation disagrees with the direction to the negative elements

Then there are only four possible signed circuits corresponding to clockwise and anticlockwise orientations, namely

A half-space arrangement breaks down the ambient space into a finite collection of cells, each defined by which side of each hyperplane it lands on.

[7] Günter M. Ziegler introduces oriented matroids via convex polytopes.

What this means is that the underlying matroids are dual and that the cocircuits are signed so that they are "orthogonal" to every circuit.

[10] Not all oriented matroids are representable—that is, not all have realizations as point configurations, or, equivalently, hyperplane arrangements.

However, in some sense, all oriented matroids come close to having realizations as hyperplane arrangements.

In particular, the Folkman–Lawrence topological representation theorem states that any oriented matroid has a realization as an arrangement of pseudospheres.

Finally, the Folkman–Lawrence topological representation theorem states that every oriented matroid of rank

[11] It is named after Jon Folkman and Jim Lawrence, who published it in 1978.

The theory of oriented matroids has influenced the development of combinatorial geometry, especially the theory of convex polytopes, zonotopes, and configurations of vectors (equivalently, arrangements of hyperplanes).

[13] The development of an axiom system for oriented matroids was initiated by R. Tyrrell Rockafellar to describe the sign patterns of the matrices arising through the pivoting operations of Dantzig's simplex algorithm; Rockafellar was inspired by Albert W. Tucker's studies of such sign patterns in "Tucker tableaux".

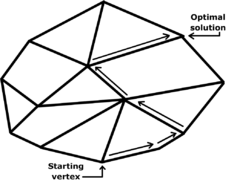

[14] The theory of oriented matroids has led to breakthroughs in combinatorial optimization.

In linear programming, it was the language in which Robert G. Bland formulated his pivoting rule, by which the simplex algorithm avoids cycles.

Similarly, it was used by Terlaky and Zhang to prove that their criss-cross algorithms have finite termination for linear programming problems.

Similar results were made in convex quadratic programming by Todd and Terlaky.

[17][18][19] Outside of combinatorial optimization, oriented matroid theory also appears in convex minimization in Rockafellar's theory of "monotropic programming" and related notions of "fortified descent".

[21] More generally, a greedoid is useful for studying the finite termination of algorithms.