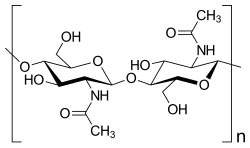

Chitin

[4] Commercially, chitin is extracted from the shells of crabs, shrimps, shellfish and lobsters, which are major by-products of the seafood industry.

In most arthropods, however, it is often modified, occurring largely as a component of composite materials, such as in sclerotin, a tanned proteinaceous matrix, which forms much of the exoskeleton of insects.

[10] Another difference between pure and composite forms can be seen by comparing the flexible body wall of a caterpillar (mainly chitin) to the stiff, light elytron of a beetle (containing a large proportion of sclerotin).

[12] The elaborate chitin gyroid construction in butterfly wings creates a model of optical devices having potential for innovations in biomimicry.

[12] Scarab beetles in the genus Cyphochilus also utilize chitin to form extremely thin scales (five to fifteen micrometres thick) that diffusely reflect white light.

[13][14] In addition, some social wasps, such as Protopolybia chartergoides, orally secrete material containing predominantly chitin to reinforce the outer nest envelopes, composed of paper.

Chitosan has a wide range of biomedical applications including wound healing, drug delivery and tissue engineering.

[32][23] Chitin is deacetylated chemically or enzymatically to produce chitosan, a highly biocompatible polymer which has found a wide range of applications in the biomedical industry.

[2][19] Chitin and chitosan are under development as scaffolds in studies of how tissue grows and how wounds heal, and in efforts to invent better bandages, surgical thread, and materials for allotransplantation.

[2][16][35] Sutures made of chitin have been experimentally developed, but their lack of elasticity and problems making thread have prevented commercial success so far.

[37] Chitin nanofibers are extracted from crustacean waste and mushrooms for possible development of products in tissue engineering, drug delivery and medicine.