Chiton

Because of this, the shell provides protection at the same time as permitting the chiton to flex upward when needed for locomotion over uneven surfaces, and even allows the animal to curl up into a ball when dislodged from rocks.

Compared with the single or two-piece shells of other molluscs, this arrangement allows chitons to roll into a protective ball when dislodged and to cling tightly to irregular surfaces.

[12] After a chiton dies, the individual valves which make up the eight-part shell come apart because the girdle is no longer holding them together, and then the plates sometimes wash up in beach drift.

[11] The protein component of the scales and sclerites is minuscule in comparison with other biomineralized structures, whereas the total proportion of matrix is 'higher' than in mollusc shells.

[11] The wide form of girdle ornament suggests it serves a secondary role; chitons can survive perfectly well without them.

The spicules are sharp, and if carelessly handled, easily penetrate the human skin, where they detach and remain as a painful irritant.

[17] Multiple gills hang down into the mantle cavity along part or all of the lateral pallial groove, each consisting of a central axis with a number of flattened filaments through which oxygen can be absorbed.

Two sacs open from the back of the mouth, one containing the radula, and the other containing a protrusible sensory subradular organ that is pressed against the substratum to taste for food.

[18] Cilia pull the food through the mouth in a stream of mucus and through the oesophagus, where it is partially digested by enzymes from a pair of large pharyngeal glands.

The intestine is divided in two by a sphincter, with the latter part being highly coiled and functioning to compact the waste matter into faecal pellets.

In some cases, however, they are modified to form ocelli, with a cluster of individual photoreceptor cells lying beneath a small aragonite-based lens.

[21] Each lens can form clear images, and is composed of relatively large, highly crystallographically aligned grains to minimize light scattering.

[19] Although chitons lack osphradia, statocysts, and other sensory organs common to other molluscs, they do have numerous tactile nerve endings, especially on the girdle and within the mantle cavity.

One theory has the chitons remembering the topographic profile of the region, thus being able to guide themselves back to their home scar by a physical knowledge of the rocks and visual input from their numerous primitive eyespots.

[30] The radular teeth of chitons are made of magnetite, and the iron crystals within these may be involved in magnetoreception,[32] the ability to sense the polarity and the inclination of the Earth's magnetic field.

This includes islands in the Caribbean, such as Trinidad, Tobago, The Bahamas, St. Maarten, Aruba, Bonaire, Anguilla and Barbados, as well as in Bermuda.

Some islanders living in South Korea also eat chiton, slightly boiled and mixed with vegetables and hot sauce.

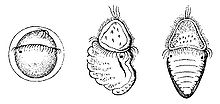

The egg has a tough spiny coat, and usually hatches to release a free-swimming trochophore larva, typical of many other mollusc groups.

In a few cases, the trochophore remains within the egg (and is then called lecithotrophic – deriving nutrition from yolk), which hatches to produce a miniature adult.

However, the exact phylogenetic position of supposed Cambrian chitons is highly controversial, and some authors have instead argued that the earliest confirmed polyplacophorans date back to the Early Ordovician.

Matthevia is a Late Cambrian polyplacophoran preserved as individual pointed valves, and sometimes considered to be a chiton,[1] although at the closest, it can only be a stem-group member of the group.

[38] Based on this and co-occurring fossils, one plausible hypothesis for the origin of polyplacophora has that they formed when an aberrant monoplacophoran was born with multiple centres of calcification, rather than the usual one.

Selection quickly acted on the resultant conical shells to form them to overlap into protective armour; their original cones are homologous to the tips of the plates of modern chitons.

[citation needed] The Greek-derived name Polyplacophora comes from the words poly- (many), plako- (tablet), and -phoros (bearing), a reference to the chiton's eight shell plates.

Most classification schemes in use today are based, at least in part, on Pilsbry's Manual of Conchology (1892–1894), extended and revised by Kaas and Van Belle (1985–1990).

The most recent classification, by Sirenko (2006),[39] is based not only on shell morphology, as usual, but also other important features, including aesthetes, girdle, radula, gills, glands, egg hull projections, and spermatozoids.

Nierstraszellidae Hanleyidae Leptochitonidae Callochitonidae Plaxiphora Nuttallochiton Hemiarthridae Acanthochitonidae Lepidochitonidae Mopaliidae Schizochitonidae Chitonidae Chaetopleuridae Ischnochitonidae