Chloroquine

[1] Certain types of malaria, resistant strains, and complicated cases typically require different or additional medication.

[3] Common side effects include muscle problems, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and skin rash.

[1] Serious side effects include problems with vision, muscle damage, seizures, and low blood cell levels.

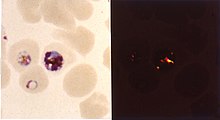

[1] As an antimalarial, it works against the asexual form of the malaria parasite in the stage of its life cycle within the red blood cell.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend against treatment of malaria with chloroquine alone due to more effective combinations.

[13] As it mildly suppresses the immune system, chloroquine is used in some autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and has an off-label indication for lupus erythematosus.

[1] Side effects include blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, headache, diarrhea, swelling legs/ankles, shortness of breath, pale lips/nails/skin, muscle weakness, easy bruising/bleeding, hearing and mental problems.

Studies with mice show that radioactively tagged chloroquine passed through the placenta rapidly and accumulated in the fetal eyes which remained present five months after the drug was cleared from the rest of the body.

[25] Symptoms of overdose may include sleepiness, vision changes, seizures, stopping of breathing, and heart problems such as ventricular fibrillation and low blood pressure.

[citation needed] Chloroquine is also a lysosomotropic agent, meaning it accumulates preferentially in the lysosomes of cells in the body.

[citation needed] The pKa for the quinoline nitrogen of chloroquine is 8.5, meaning it is about 10% deprotonated at physiological pH (per the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation).

[citation needed] The lysosomotropic character of chloroquine is believed to account for much of its antimalarial activity; the drug concentrates in the acidic food vacuole of the parasite and interferes with essential processes.

Its lysosomotropic properties further allow for its use for in vitro experiments pertaining to intracellular lipid related diseases,[31][32] autophagy, and apoptosis.

[38] Verapamil, a Ca2+ channel blocker, has been found to restore both the chloroquine concentration ability and sensitivity to this drug.

Other agents which have been shown to reverse chloroquine resistance in malaria are chlorpheniramine, gefitinib, imatinib, tariquidar and zosuquidar.

Chloroquine, a synthetic analogue with the same mechanism of action was discovered in 1934, by Hans Andersag and coworkers at the Bayer laboratories, who named it resochin.

After Allied forces arrived in Tunis, sontochin fell into the hands of Americans, who sent the material back to the United States for analysis, leading to renewed interest in chloroquine.

[58] Chloroquine, in various chemical forms, is used to treat and control surface growth of anemones and algae, and many protozoan infections in aquariums,[59] e.g. the fish parasite Amyloodinium ocellatum.

[40]: 1237 In biomedicinal science, chloroquine is used for in vitro experiments to inhibit lysosomal degradation of protein products.

Chloroquine was proposed as a treatment for SARS, with in vitro tests inhibiting the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV).

[61][62] In October 2004, a published report stated that chloroquine acts as an effective inhibitor of the replication of SARS-CoV in vitro.

[66][67][68][69][70][71] Administration of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine to COVID-19 patients, either as monotherapies or in conjunction with azithromycin, has been associated with deleterious outcomes, such as QT prolongation.

[75] Several countries initially used chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for treatment of persons hospitalized with COVID-19 (as of March 2020), though the drug was not formally approved through clinical trials.

[79] On 24 April 2020, citing the risk of "serious heart rhythm problems", the FDA posted a caution against using the drug for COVID-19 "outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial".

[81][82] On 15 June 2020, the FDA revoked its emergency use authorization, stating that it was "no longer reasonable to believe" that the drug was effective against COVID-19 or that its benefits outweighed "known and potential risks".

[83][84][85] In fall of 2020, the National Institutes of Health issued treatment guidelines recommending against the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 except as part of a clinical trial.

o Elevated occurrence of chloroquine- or multi-resistant malaria

o Occurrence of chloroquine-resistant malaria

o No Plasmodium falciparum or chloroquine-resistance

o No malaria