Christianity and Islam

[3][4] Muslims view Christians to be People of the Book, and also regard them as kafirs (unbelievers) committing shirk (polytheism) because of the Trinity, and thus, contend that they must be dhimmis (religious taxpayers) under Sharia law.

However, the rise of harsher criticism during the Enlightenment has led to a diversity of views concerning the authority and inerrancy of the Bible in different denominations.

[18] Muslims believe that Jesus was given the Injil (Greek evangel, or Gospel) by God, however that parts or the entirety of these teachings were lost or distorted (tahrif) to produce the Hebrew Bible and the Christian New Testament.

Christianity teaches that Jesus was condemned to death by the Sanhedrin and the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, crucified, and after three days, resurrected.

[28] Muslims revere Muhammad as the embodiment of the perfect believer and take his actions and sayings as a model of ideal conduct.

Unlike Jesus, who Christians believe was God's son, Muhammad was a mortal, albeit with extraordinary qualities.

The vast majority of the world's Christians adhere to the doctrine of the Trinity, which in creedal formulations states that God is three hypostases (the Father, the Son and the Spirit) in one ousia (substance).

[citation needed] Most Christians believe that the Paraclete referred to in the Gospel of John, who was manifested on the day of Pentecost, is the Holy Spirit.

"The plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator, in the first place amongst whom are the Muslims; these profess to hold the faith of Abraham, and together with us they adore the one, merciful God, mankind's judge on the last day.

All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23–25).

He emphasizes the need for what he considers a rational and coherent ethical framework, contrasting Christian concepts like peccatism (inherent human sinfulness) and saviorism (belief in Jesus as the redeemer) with Islamic views.

And we remark that Moses received the Law on Mount Sinai, with God appearing in the sight of all the people in cloud, and fire, and darkness, and storm.

And how is it that God did not in your presence present this man with the book to which you refer, even as He gave the Law to Moses, with the people looking on and the mountain smoking, so that you, too, might have certainty?'

[48]Theophanes the Confessor (died c.822) wrote a series of chronicles (284 onwards and 602–813 AD)[49][50][51] based initially on those of the better known George Syncellus.

He tried deceitfully to placate her by saying, 'I keep seeing a vision of a certain angel called Gabriel, and being unable to bear his sight, I faint and fall down.

'In the work A History of Christian-Muslim Relations,[52] Hugh Goddard mentions both John of Damascus and Theophanes and goes on to consider the relevance of Niketas Byzantios [clarification needed] who formulated replies to letters on behalf of Emperor Michael III (842-867).

Goddard sums up Niketas' view: In short, Muhammad was an ignorant charlatan who succeeded by imposture in seducing the ignorant barbarian Arabs into accepting a gross, blaspheming, idolatrous, demoniac religion, which is full of futile errors, intellectual enormities, doctrinal errors and moral aberrations.Goddard further argues that Niketas demonstrates in his work a knowledge of the entire Quran, including an extensive knowledge of Suras 2–18.

Niketas' account from behind the Byzantine frontier apparently set a strong precedent for later writing both in tone and points of argument.

This view, evidently confusing Islam with the pre-Christian Graeco-Roman Religion, appears to reflect misconceptions prevalent in Western Christian society at the time.

On the other hand, ecclesiastic writers such as Amatus of Montecassino or Geoffrey Malaterra in Norman Southern Italy, who occasionally lived among Muslims themselves, would depict at times Muslims in a negative way but would depict equally any other (ethnic) group that was opposed to the Norman rule such as Byzantine Greeks or Italian Lombards.

[53] Similarities were occasionally acknowledged such as by Pope Gregory VII wrote in a letter to the Hammadid emir an-Nasir that both Christians and Muslims "worship and confess the same God though in diverse forms and daily praise".

[54] In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Muhammad is in the ninth ditch of Malebolge, the eighth realm, designed for those who have caused schism; specifically, he was placed among the Sowers of Religious Discord.

Muhammad is represented in a 15th-century fresco Last Judgment by Giovanni da Modena and drawing on Dante, in the San Petronio Basilica in Bologna,[55] as well as in artwork by Salvador Dalí, Auguste Rodin, William Blake, and Gustave Doré.

[58] In Lumen gentium, the Second Vatican Council declares that the plan of salvation also includes Muslims, due to their professed monotheism.

As both were in conflict with the Catholic Holy Roman Empire, numerous exchanges occurred, exploring religious similarities and the possibility of trade and military alliances.

[62] For instance, Joseph Smith, the founding prophet of Mormonism, was referred to as "the modern Mahomet" by the New York Herald,[63] shortly after his murder in June 1844.

Comparison of the Mormon and Muslim prophets still occurs today, sometimes for derogatory or polemical reasons[65] but also for more scholarly and neutral purposes.

Mormon-Muslim relations have historically been cordial;[67] recent years have seen increasing dialogue between adherents of the two faiths, and cooperation in charitable endeavors, especially in the Middle and Far East.

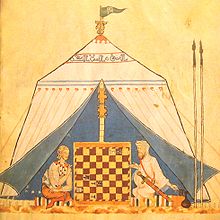

[79] During the High Middle Ages, the Islamic world was at its cultural peak, supplying information and ideas to Europe, via Al-Andalus, Sicily and the Crusader kingdoms in the Levant.

These included Latin translations of the Greek Classics and of Arabic texts in astronomy, mathematics, science, and medicine.