Christendom

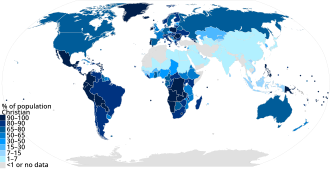

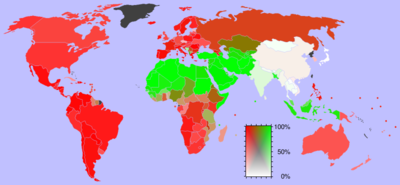

[2] Following the spread of Christianity from the Levant to Europe and North Africa during the early Roman Empire, Christendom has been divided in the pre-existing Greek East and Latin West.

The history of the Christian world spans about 2,000 years and includes a variety of socio-political developments, as well as advancements in the arts, architecture, literature, science, philosophy, politics and technology.

[8][9][10] The Anglo-Saxon term crīstendōm appears to have been coined in the 9th century by a scribe somewhere in southern England, possibly at the court of king Alfred the Great of Wessex.

The scribe was translating Paulus Orosius' book History Against the Pagans (c. 416) and in need for a term to express the concept of the universal culture focused on Jesus Christ.

[14] Canadian theology professor Douglas John Hall stated (1997) that "Christendom" [...] means literally the dominion or sovereignty of the Christian religion.

"[4] Thomas John Curry, Roman Catholic auxiliary bishop of Los Angeles, defined (2001) Christendom as "the system dating from the fourth century by which governments upheld and promoted Christianity.

[20] Early Christendom would close at the end of imperial persecution of Christians after the ascension of Constantine the Great and the Edict of Milan in AD 313 and the First Council of Nicaea in 325.

[26] Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 proclaiming toleration for the Christian religion, and convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325 whose Nicene Creed included belief in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church".

The clergy, like Plato's guardians, were placed in authority... by their talent as shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of state and church.

In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 AD onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as even Plato could desire [for such guardians]... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the one hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the flesh added to the awe in which lay sinners held them....[34]After the collapse of Charlemagne's empire, the southern remnants of the Holy Roman Empire became a collection of states loosely connected to the Holy See of Rome.

Tensions between Pope Innocent III and secular rulers ran high, as the pontiff exerted control over their temporal counterparts in the west and vice versa.

[48] Before the modern period, Christendom was in a general crisis at the time of the Renaissance Popes because of the moral laxity of these pontiffs and their willingness to seek and rely on temporal power as secular rulers did.

In the early 16th century, Baldassare Castiglione (The Book of the Courtier) laid out his vision of the ideal gentleman and lady, while Machiavelli cast a jaundiced eye on "la verità effetuale delle cose"—the actual truth of things—in The Prince, composed, humanist style, chiefly of parallel ancient and modern examples of Virtù.

During these intermediate times, popes strove to make Rome the capital of Christendom while projecting it through art, architecture, and literature as the center of a Golden Age of unity, order, and peace.

Rome in the Renaissance under the papacy not only acted as guardian and transmitter of these elements stemming from the Roman Empire but also assumed the role as artificer and interpreter of its myths and meanings for the peoples of Europe from the Middle Ages to modern times...

[52] The blossoming of renaissance humanism was made very much possible due to the universality of the institutions of Catholic Church and represented by personalities such as Pope Pius II, Nicolaus Copernicus, Leon Battista Alberti, Desiderius Erasmus, sir Thomas More, Bartolomé de Las Casas, Leonardo da Vinci and Teresa of Ávila.

[61] Instead, the focus of Western history shifts to the development of the nation-state, accompanied by increasing atheism and secularism, culminating with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars at the turn of the 19th century.

[24] American Catholic bishop Thomas John Curry stated in 2001 that the end of Christendom came about because modern governments refused to "uphold the teachings, customs, ethos, and practice of Christianity".

[15] He argued the First Amendment to the United States Constitution (1791) and the Second Vatican Council's Declaration on Religious Freedom (1965) are two of the most important documents setting the stage for its end.

The only surviving monarchy with an established church, Britain, was severely damaged by the war, lost most of Ireland due to Catholic–Protestant infighting, and was starting to lose grip on its colonies.

[18] Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the Catholic Church is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization.

[70] Christianity also had a strong impact on all other aspects of life: marriage and family, education, the humanities and sciences, the political and social order, the economy, and the arts.

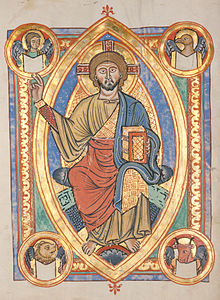

Religious images are used to some extent by the Abrahamic Christian faith, and often contain highly complex iconography, which reflects centuries of accumulated tradition.

A number of Christian saints are traditionally represented by a symbol or iconic motif associated with their life, termed an attribute or emblem, in order to identify them.

After the Renaissance of the 12th century, medieval Europe saw a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth.

[103] The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption of gunpowder and the astrolabe, the invention of spectacles, and greatly improved water mills, building techniques, agriculture in general, clocks, and ships.

The rediscovery of ancient scientific texts was accelerated after the Fall of Constantinople, and the invention of printing which would democratize learning and allow a faster propagation of new ideas.

The era is marked by such profound technical advancements like the printing press, linear perspectivity, patent law, double shell domes or Bastion fortresses.

In contrast, the term Holy Orders is used by many Christian churches to refer to ordination or to a group of individuals who are set apart for a special role or ministry.

Contemporary conservatives meanwhile have reasserted what has been termed a "complementarian" position, promoting the traditional belief that the Bible ordains different roles and responsibilities for women and men in the Church and family.