Geometry

[3] Originally developed to model the physical world, geometry has applications in almost all sciences, and also in art, architecture, and other activities that are related to graphics.

For example, methods of algebraic geometry are fundamental in Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, a problem that was stated in terms of elementary arithmetic, and remained unsolved for several centuries.

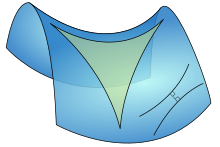

One of the oldest such discoveries is Carl Friedrich Gauss's Theorema Egregium ("remarkable theorem") that asserts roughly that the Gaussian curvature of a surface is independent from any specific embedding in a Euclidean space.

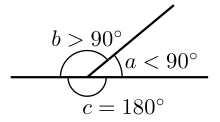

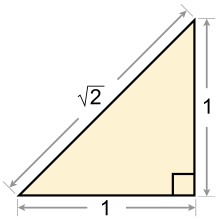

[5][6] Early geometry was a collection of empirically discovered principles concerning lengths, angles, areas, and volumes, which were developed to meet some practical need in surveying, construction, astronomy, and various crafts.

[7] Later clay tablets (350–50 BC) demonstrate that Babylonian astronomers implemented trapezoid procedures for computing Jupiter's position and motion within time-velocity space.

[8] South of Egypt the ancient Nubians established a system of geometry including early versions of sun clocks.

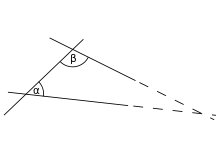

[9][10] In the 7th century BC, the Greek mathematician Thales of Miletus used geometry to solve problems such as calculating the height of pyramids and the distance of ships from the shore.

355 BC) developed the method of exhaustion, which allowed the calculation of areas and volumes of curvilinear figures,[15] as well as a theory of ratios that avoided the problem of incommensurable magnitudes, which enabled subsequent geometers to make significant advances.

[17] The Elements was known to all educated people in the West until the middle of the 20th century and its contents are still taught in geometry classes today.

[18] Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC) of Syracuse, Italy used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabola with the summation of an infinite series, and gave remarkably accurate approximations of pi.

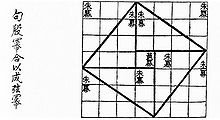

Chapter 12, containing 66 Sanskrit verses, was divided into two sections: "basic operations" (including cube roots, fractions, ratio and proportion, and barter) and "practical mathematics" (including mixture, mathematical series, plane figures, stacking bricks, sawing of timber, and piling of grain).

[26] Thābit ibn Qurra (known as Thebit in Latin) (836–901) dealt with arithmetic operations applied to ratios of geometrical quantities, and contributed to the development of analytic geometry.

[40] At the start of the 19th century, the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky (1792–1856), János Bolyai (1802–1860), Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) and others[41] led to a revival of interest in this discipline, and in the 20th century, David Hilbert (1862–1943) employed axiomatic reasoning in an attempt to provide a modern foundation of geometry.

[69] Hilbert, in his work on creating a more rigorous foundation for geometry, treated congruence as an undefined term whose properties are defined by axioms.

However, some problems turned out to be difficult or impossible to solve by these means alone, and ingenious constructions using neusis, parabolas and other curves, or mechanical devices, were found.

Traditional geometry allowed dimensions 1 (a line or curve), 2 (a plane or surface), and 3 (our ambient world conceived of as three-dimensional space).

[75] Symmetric shapes such as the circle, regular polygons and platonic solids held deep significance for many ancient philosophers[76] and were investigated in detail before the time of Euclid.

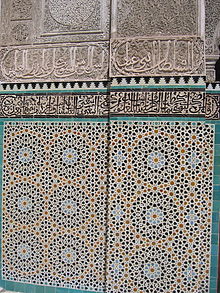

[39] Symmetric patterns occur in nature and were artistically rendered in a multitude of forms, including the graphics of Leonardo da Vinci, M. C. Escher, and others.

Felix Klein's Erlangen program proclaimed that, in a very precise sense, symmetry, expressed via the notion of a transformation group, determines what geometry is.

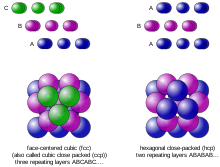

[87] As it models the space of the physical world, it is used in many scientific areas, such as mechanics, astronomy, crystallography,[88] and many technical fields, such as engineering,[89] architecture,[90] geodesy,[91] aerodynamics,[92] and navigation.

[93] The mandatory educational curriculum of the majority of nations includes the study of Euclidean concepts such as points, lines, planes, angles, triangles, congruence, similarity, solid figures, circles, and analytic geometry.

[94] Euclidean vectors are used for a myriad of applications in physics and engineering, such as position, displacement, deformation, velocity, acceleration, force, etc.

In particular, differential geometry is of importance to mathematical physics due to Albert Einstein's general relativity postulation that the universe is curved.

Often claimed to be the most aesthetically pleasing ratio of lengths, it is frequently stated to be incorporated into famous works of art, though the most reliable and unambiguous examples were made deliberately by artists aware of this legend.

[30] For instance, the introduction of coordinates by René Descartes and the concurrent developments of algebra marked a new stage for geometry, since geometric figures such as plane curves could now be represented analytically in the form of functions and equations.

[150] "Three scientists, Ibn al-Haytham, Khayyam, and al-Tusi, had made the most considerable contribution to this branch of geometry whose importance came to be completely recognized only in the 19th century.

In essence, their propositions concerning the properties of quadrangles which they considered, assuming that some of the angles of these figures were acute of obtuse, embodied the first few theorems of the hyperbolic and the elliptic geometries.

By their works on the theory of parallel lines Arab mathematicians directly influenced the relevant investigations of their European counterparts.

The first European attempt to prove the postulate on parallel lines—made by Witelo, the Polish scientists of the 13th century, while revising Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazir)—was undoubtedly prompted by Arabic sources.

The proofs put forward in the 14th century by the Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson, who lived in southern France, and by the above-mentioned Alfonso from Spain directly border on Ibn al-Haytham's demonstration.