Christianity and science

[8] Duhem concluded that "the mechanics and physics of which modern times are justifiably proud to proceed, by an uninterrupted series of scarcely perceptible improvements, from doctrines professed in the heart of the medieval schools".

For instance, among early Christian teachers, from Tertullian (c. 160–220) held a generally negative opinion of Greek philosophy, while Origen (c. 185–254) regarded it much more favourably and required his students to read nearly every work available to them.

[31][32] Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo (354–430) and Thomas Aquinas[33] held that scriptures can have multiple interpretations on certain areas where the matters were far beyond their reach, therefore one should leave room for future findings to shed light on the meanings.

Heilbron,[41] Alistair Cameron Crombie, David Lindberg,[42] Edward Grant, Thomas Goldstein,[43] and Ted Davis have reviewed the popular notion that medieval Christianity was a negative influence in the development of civilization and science.

In their views, not only did the monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but the medieval church promoted learnings and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

[50] Lindberg reports that "the late medieval scholar rarely experienced the coercive power of the church and would have regarded himself as free (particularly in the natural sciences) to follow reason and observation wherever they led.

For instance, when Georg Calixtus ventured, in interpreting the Psalms, to question the accepted belief that "the waters above the heavens" were contained in a vast receptacle upheld by a solid vault, he was bitterly denounced as heretical.

[76] Also, the claim that people of the Middle Ages widely believed that the Earth was flat was first propagated in the same period that originated the conflict thesis[77] and is still very common in popular culture.

"[77][78] From the fall of Rome to the time of Columbus, all major scholars and many vernacular writers interested in the physical shape of the earth held a spherical view with the exception of Lactantius and Cosmas.

[80] He presented Dutch historian R. Hooykaas' argument that a biblical world-view holds all the necessary antidotes for the hubris of Greek rationalism: a respect for manual labour, leading to more experimentation and empiricism, and a supreme God that left nature and open to emulation and manipulation.

Numbers has also argued, "Despite the manifest shortcomings of the claim that Christianity gave birth to science—most glaringly, it ignores or minimizes the contributions of ancient Greeks and medieval Muslims—it too, refuses to succumb to the death it deserves.

[94] Historian John Heilbron says that "The Roman Catholic Church gave more financial and social support to the study of astronomy for over six centuries, from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment, then any other, and probably all, other Institutions.

Heilbron,[104] A.C. Crombie, David Lindberg,[105] Edward Grant, Thomas Goldstein,[106] and Ted Davis, have argued that the Church had a significant, positive influence on the development of Western civilization.

They hold that, not only did monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but that the Church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

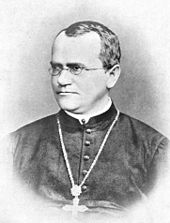

Other notable priest scientists have included Albertus Magnus, Robert Grosseteste, Nicholas Steno, Francesco Grimaldi, Giambattista Riccioli, Roger Boscovich, and Athanasius Kircher.

[112] The English science historian James Burke examines the impact of Cistercian waterpower, derived from Roman watermill technology such as that of Barbegal aqueduct and mill near Arles in the fourth of his ten-part Connections TV series, called "Faith in Numbers".

[113] Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the teaching of science in Jesuit schools, as laid down in the Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum Societatis Iesu ("The Official Plan of studies for the Society of Jesus") of 1599,[114] was almost entirely based on the works of Aristotle.

[116] According to Jonathan Wright in his book God's Soldiers, by the eighteenth century the Jesuits had "contributed to the development of pendulum clocks, pantographs, barometers, reflecting telescopes and microscopes, to scientific fields as various as magnetism, optics and electricity.

[118] The Society of Jesus introduced, according to Thomas Woods, "a substantial body of scientific knowledge and a vast array of mental tools for understanding the physical universe, including the Euclidean geometry that made planetary motion comprehensible".

Some of the first colleges and universities in America, including Harvard,[134] Yale,[135] Princeton,[136] Columbia,[137] Dartmouth,[138] Pennsylvania,[139][140] Duke,[141] Boston,[142] Williams, Bowdoin, Middlebury,[143] and Amherst, all were founded by mainline Protestant denominations.

[159] One of the greatest Assyrian achievements of the fourth century was the founding of one of the oldest universities in the world, the School of Nisibis, which had three departments, theology, philosophy and medicine, and which became a magnet and center of intellectual development in the Middle East.

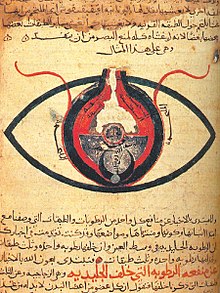

[161][162][163][164] In the field of Optics, Nestorian Christian Hunayn ibn-Ishaq's textbook on ophthalmology called the Ten Treatises on the Eye, which was written in 950 A.D., remained the authoritative source on the subject in the western world until the 1800s.

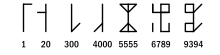

[165] It was a Christian scholar and Bishop from Nisibis named Severus Sebokht who was the first to describe and incorporate Indian mathematical symbols in the mid 7th century, which were then adopted into Islamic culture and are now known as the Arabic numerals.

[177][178] The common and persistent myth claiming that Islamic scholars "saved" the classical work of Aristotle and other Greek philosophers from destruction and then graciously passed it on to Europe is baseless.

[183] The Byzantines pioneered the concept of the hospital as an institution offering medical care and the possibility of a cure for the patients, as a reflection of the ideals of Christian charity, rather than merely a place to die.

Historian Maria Mavroudi recounts:[187] When asked how it was possible for him to know all that he did, he [Cyril] drew an analogy between the Muslim reaction to his erudition and the pride of someone who kept sea water in a wine skin and boasted of possessing a rare liquid.

Many well-known historical figures who influenced Western science considered themselves Christian such as Nicolaus Copernicus,[198] Galileo Galilei,[199] Johannes Kepler,[200] Isaac Newton[201] Robert Boyle,[202] Francis Bacon,[203] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,[204] Emanuel Swedenborg,[205] Alessandro Volta,[206] Carl Friedrich Gauss,[207] Antoine Lavoisier,[208] André-Marie Ampère, John Dalton,[209] James Clerk Maxwell,[210][211] William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin,[212] Louis Pasteur,[213] Michael Faraday,[214] and J. J.

In the concluding General Scholium to the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, he wrote: "This most beautiful System of the Sun, Planets and Comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being."

[235] More recently, Thomas E. Woods, Jr., asserts that, despite the widely held conception of the Catholic Church as being anti-science, this conventional wisdom has been the subject of "drastic revision" by historians of science over the last 50 years.

Since the creation of the Conflict thesis by Andrew Dickson White and John William Draper in the late nineteenth century, religion has been depicted as oppressive and oppositional to science.

France , early 15th century.