Christianity in the 4th century

In April 311, Galerius, who had previously been one of the leading figures in the persecutions, issued an edict permitting the practice of the Christian religion under his rule.

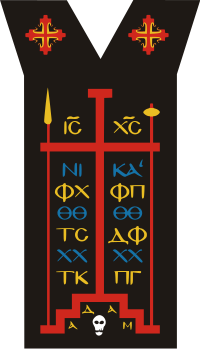

According to these sources, Constantine looked up to the sun before the battle and saw a cross of light above it, and with it the Greek words "ΕΝ ΤΟΥΤΩ ΝΙΚΑ" ("by this, conquer!

", often rendered in the Latin "in hoc signo vinces"); Constantine commanded his troops to adorn their shields with a Christian symbol (the Chi-Ro), and thereafter they were victorious.

Thereafter, he supported the Church financially, built various basilicas, granted privileges (e.g., exemption from certain taxes) to clergy, promoted Christians to high ranking offices, and returned property confiscated during the reign of Diocletian.

[11] Constantine utilized Christian symbols early in his reign but still encouraged traditional Roman religious practices including sun worship.

[14]: 317, 320 Bryant explains that, "once those within a sect determine that "the 'spirit' no longer resides in the parent body, 'the holy and the pure' typically find themselves compelled – either by conviction or coercion – to withdraw and establish their own counter-church, consisting of the 'gathered remnant' of God's elect".

[14]: 332 During the Melitian schism and the beginnings of the Donatist division, bishop Cyprian had felt compelled to "grant one laxist concession after another in the course of his desperate struggle to preserve the Catholic church".

Brown says Roman authorities had shown no hesitation in "taking out" the Christian church they had seen as a threat to empire, and Constantine and his successors did the same, for the same reasons.

He modified these practices to resemble Christian traditions such as the episcopal structure and public charity (hitherto unknown in Roman paganism).

His reforms attempted to create a form of religious heterogeneity by, among other things, reopening pagan temples, accepting Christian bishops previously exiled as heretics, promoting Judaism, and returning Church lands to their original owners.

By the early 4th century a group in North Africa, later called Donatists, who believed in a very rigid interpretation of Christianity that excluded many who had abandoned the faith during the Diocletian persecutions, created a crisis in the western Empire.

Emperor Constantine was of divided opinions, but he largely backed the Athanasian faction (though he was baptized on his death bed by the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia).

Emperor Julian favored a return the traditional Roman/Greek religion, but this trend was quickly quashed by his successor Jovian, a supporter of the Athanasian faction.

Another result of the council was an agreement on the date of the Christian Passover (Pascha in Greek; Easter in modern English), the most important feast of the ecclesiastical calendar.

[29] In 359, a double council of Eastern and Western bishops affirmed a formula stating that the Father and the Son were similar in accord with the scriptures, the crowning victory for Arianism.

[34] Late Antique Christianity produced a great many renowned Church Fathers who wrote volumes of theological texts, including Augustine of Hippo, Gregory Nazianzus, Cyril of Jerusalem, Ambrose of Milan, Jerome, and others.

After his death (or, according to some sources, during his life) he was given the Greek surname chrysostomos, meaning "golden mouthed", rendered in English as Chrysostom.

At Tabenna around 323, Saint Pachomius chose to mould his disciples into a more organized community in which the monks lived in individual huts or rooms (cellula in Latin) but worked, ate, and worshipped in shared space.

From there monasticism quickly spread out first to Palestine and the Judean Desert, Syria, North Africa and eventually the rest of the Roman Empire.

Orthodox monasticism does not have religious orders as in the West,[41] so there are no formal monastic rules; rather, each monk and nun is encouraged to read all of the Holy Fathers and emulate their virtues.

He was called to become Bishop of Tours in 372, where he established a monastery at Marmoutiers on the opposite bank of the Loire River, a few miles upstream from the city.

In Egypt he had been attracted to the isolated life of hermits, which he considered the highest form of monasticism, yet the monasteries he founded were all organized monastic communities.

Most significant for the future development of monasticism were Cassian's Institutes, which provided a guide for monastic life and his Conferences, a collection of spiritual reflections.

Honoratus of Marseilles was a wealthy Gallo-Roman aristocrat, who after a pilgrimage to Egypt, founded the Monastery of Lérins, on an island lying off the modern city of Cannes.

[43] Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, in his Easter letter of 367,[44] which was approved at the Quinisext Council, listed the same twenty-seven New Testament books as found in the Canon of Trent.

Emperor Diocletian divided the administration of the eastern and western portions of the empire in the early 4th century, though subsequent leaders (including Constantine) aspired to and sometimes gained control of both regions.

In the West, the collapse of civil government left the Church practically in charge in many areas, and bishops took to administering secular cities and domains.

He wrote to the young shah: It was enough to make any Persian ruler conditioned by 300 years of war with Rome suspicious of the emergence of a fifth column.

The outstanding key to understanding this expansion is the active participation of the laymen – the involvement of a large percentage of the church's believers in missionary evangelism.

Christians were found among the Hephthalite Huns from the 5th century, and the Mesopotamian patriarch assigned two bishops (John of Resh-aina and Thomas the Tanner) to both peoples[vague], with the result that many were baptized.