Chromosome

This is an accepted version of this page A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism.

Aided by chaperone proteins, the histones bind to and condense the DNA molecule to maintain its integrity.

[1][2] These eukaryotic chromosomes display a complex three-dimensional structure that has a significant role in transcriptional regulation.

[4] Before this stage occurs, each chromosome is duplicated (S phase), and the two copies are joined by a centromere—resulting in either an X-shaped structure if the centromere is located equatorially, or a two-armed structure if the centromere is located distally; the joined copies are called 'sister chromatids'.

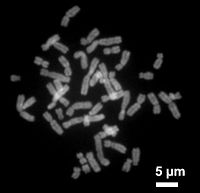

During metaphase, the duplicated structure (called a 'metaphase chromosome') is highly condensed and thus easiest to distinguish and study.

[6] Chromosomal recombination during meiosis and subsequent sexual reproduction plays a crucial role in genetic diversity.

If these structures are manipulated incorrectly, through processes known as chromosomal instability and translocation, the cell may undergo mitotic catastrophe.

The term 'chromosome' is sometimes used in a wider sense to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin in cells, which may or may not be visible under light microscopy.

In a narrower sense, 'chromosome' can be used to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin during cell division, which are visible under light microscopy due to high condensation.

[14] In a series of experiments beginning in the mid-1880s, Theodor Boveri gave definitive contributions to elucidating that chromosomes are the vectors of heredity, with two notions that became known as 'chromosome continuity' and 'chromosome individuality'.

[15] Wilhelm Roux suggested that every chromosome carries a different genetic configuration, and Boveri was able to test and confirm this hypothesis.

Aided by the rediscovery at the start of the 1900s of Gregor Mendel's earlier experimental work, Boveri identified the connection between the rules of inheritance and the behaviour of the chromosomes.

[17] Ernst Mayr remarks that the theory was hotly contested by some famous geneticists, including William Bateson, Wilhelm Johannsen, Richard Goldschmidt and T.H.

His error was copied by others, and it was not until 1956 that the true number (46) was determined by Indonesian-born cytogeneticist Joe Hin Tjio.

[20] The chromosomes of most bacteria (also called genophores), can range in size from only 130,000 base pairs in the endosymbiotic bacteria Candidatus Hodgkinia cicadicola[21] and Candidatus Tremblaya princeps,[22] to more than 14,000,000 base pairs in the soil-dwelling bacterium Sorangium cellulosum.

For instance, Spirochaetes such as Borrelia burgdorferi (causing Lyme disease), contain a single linear chromosome.

This structure is, however, dynamic and is maintained and remodeled by the actions of a range of histone-like proteins, which associate with the bacterial chromosome.

These are circular structures in the cytoplasm that contain cellular DNA and play a role in horizontal gene transfer.

Chromatin contains the vast majority of the DNA in an organism, but a small amount inherited maternally can be found in the mitochondria.

They cease to function as accessible genetic material (transcription stops) and become a compact transportable form.

The loops of thirty-nanometer chromatin fibers are thought to fold upon themselves further to form the compact metaphase chromosomes of mitotic cells.

Mitotic metaphase chromosomes are best described by a linearly organized longitudinally compressed array of consecutive chromatin loops.

[37] During mitosis, microtubules grow from centrosomes located at opposite ends of the cell and also attach to the centromere at specialized structures called kinetochores, one of which is present on each sister chromatid.

Like many sexually reproducing species, humans have special gonosomes (sex chromosomes, in contrast to autosomes).

In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia and 48 in oogonia, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism.

[52] Human examples include: Exposure of males to certain lifestyle, environmental and/or occupational hazards may increase the risk of aneuploid spermatozoa.

[57] In particular, risk of aneuploidy is increased by tobacco smoking,[58][59] and occupational exposure to benzene,[60] insecticides,[61][62] and perfluorinated compounds.

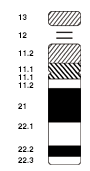

- Chromatid

- Centromere

- Short arm

- Long arm