Karyotype

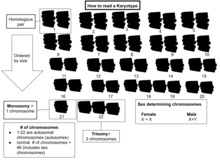

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes.

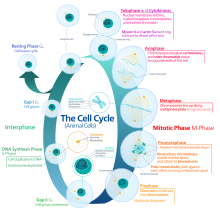

Karyotyping generally combines light microscopy and photography in the metaphase of the cell cycle, and results in a photomicrographic (or simply micrographic) karyogram.

Attention is paid to their length, the position of the centromeres, banding pattern, any differences between the sex chromosomes, and any other physical characteristics.

Karyotypes can be used for many purposes; such as to study chromosomal aberrations, cellular function, taxonomic relationships, medicine and to gather information about past evolutionary events (karyosystematics).

The sex of an unborn fetus can be predicted by observation of interphase cells (see amniotic centesis and Barr body).

A major exception to diploidy in humans is gametes (sperm and egg cells) which are haploid with 23 unpaired chromosomes, and this ploidy is not shown in these karyograms.

Such bands and sub-bands are used by the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature to describe locations of chromosome abnormalities.

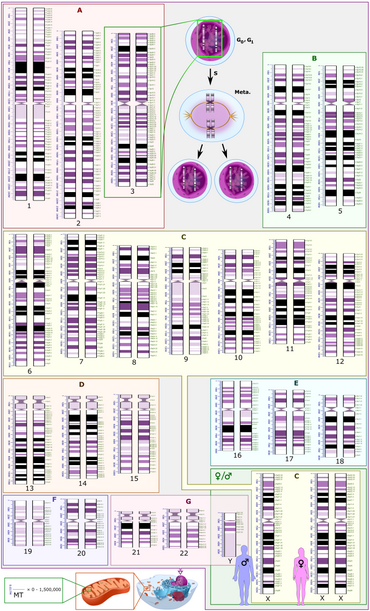

Based on the karyogram characteristics of size, position of the centromere and sometimes the presence of a chromosomal satellite (a segment distal to a secondary constriction), the human chromosomes are classified into the following groups:[15] Alternatively, the human genome can be classified as follows, based on pairing, sex differences, as well as location within the cell nucleus versus inside mitochondria: Schematic karyograms generally display a DNA copy number corresponding to the G0 phase of the cellular state (outside of the replicative cell cycle) which is the most common state of cells.

At top center in the schematic karyogram, it also shows the chromosome 3 pair after having undergone DNA synthesis, occurring in the S phase (annotated as S) of the cell cycle.

In reality, during the G0 and G1 phases, nuclear DNA is dispersed as chromatin and does not show visually distinguishable chromosomes even on micrography.

In a review, Godfrey and Masters conclude: In our view, it is unlikely that one process or the other can independently account for the wide range of karyotype structures that are observed ...

But, used in conjunction with other phylogenetic data, karyotypic fissioning may help to explain dramatic differences in diploid numbers between closely related species, which were previously inexplicable.

A spectacular example of variability between closely related species is the muntjac, which was investigated by Kurt Benirschke and Doris Wurster.

When they looked at the karyotype of the closely related Indian muntjac, Muntiacus muntjak, they were astonished to find it had female = 6, male = 7 chromosomes.

But when they obtained a couple more specimens they confirmed [their findings].The number of chromosomes in the karyotype between (relatively) unrelated species is hugely variable.

Polyploid series in related species which consist entirely of multiples of a single basic number are known as euploid.In many instances, endopolyploid nuclei contain tens of thousands of chromosomes (which cannot be exactly counted).

The cells do not always contain exact multiples (powers of two), which is why the simple definition 'an increase in the number of chromosome sets caused by replication without cell division' is not quite accurate.This process (especially studied in insects and some higher plants such as maize) may be a developmental strategy for increasing the productivity of tissues which are highly active in biosynthesis.

[46]The phenomenon occurs sporadically throughout the eukaryote kingdom from protozoa to humans; it is diverse and complex, and serves differentiation and morphogenesis in many ways.

[52] There is some evidence from the case of the mollusc Thais lapillus (the dog whelk) on the Brittany coast, that the two chromosome morphs are adapted to different habitats.

In about 6,500 sq mi (17,000 km2), the Hawaiian Islands have the most diverse collection of drosophilid flies in the world, living from rainforests to subalpine meadows.

The inversions, when plotted in tree form (and independent of all other information), show a clear "flow" of species from older to newer islands.

In addition, the differently stained regions and sub-regions are given numerical designations from proximal to distal on the chromosome arms.

[62] Multicolor FISH and the older spectral karyotyping are molecular cytogenetic techniques used to simultaneously visualize all the pairs of chromosomes in an organism in different colors.

Because there are a limited number of spectrally distinct fluorophores, a combinatorial labeling method is used to generate many different colors.

[64] Multicolor FISH is used to identify structural chromosome aberrations in cancer cells and other disease conditions when Giemsa banding or other techniques are not accurate enough.

It is Neo-Latin from Ancient Greek κάρυον karyon, "kernel", "seed", or "nucleus", and τύπος typos, "general form") The next stage took place after the development of genetics in the early 20th century, when it was appreciated that chromosomes (that can be observed by karyotype) were the carrier of genes.

The term karyotype as defined by the phenotypic appearance of the somatic chromosomes, in contrast to their genic contents was introduced by Grigory Levitsky who worked with Lev Delaunay, Sergei Navashin, and Nikolai Vavilov.

[72] In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia and 48 in oogonia, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism.