Chuck (engineering)

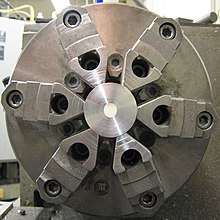

A chuck is a specialized type of clamp used to hold an object with radial symmetry, especially a cylinder.

Chucks on some lathes have jaws that move independently, allowing them to hold irregularly shaped objects.

Instead of jaws, a chuck may use magnetism, vacuum, or collets, which are flexible collars or sleeves that fit closely around the tool or workpiece and grip it when squeezed.

These chucks are best suited to grip circular or hexagonal cross-sections when very fast, reasonably accurate (±0.005 inch [0.125 mm] TIR) centering is desired.

[citation needed] There are hybrid self-centering chucks that have adjustment screws that can be used to further improve the concentricity after the workpiece has been gripped by the scroll jaws.

This feature is meant to combine the speed and ease of the scroll plate's self-centering with the run-out eliminating controllability of an independent-jaw chuck.

This type of chuck is used on tools ranging from professional equipment to inexpensive hand and power drills for domestic use.

Some high-precision chucks use ball thrust bearings to reduce friction in the closing mechanism and maximize drilling torque.

The independence of the jaws makes these chucks ideal for (a) gripping non-circular cross sections and (b) gripping circular cross sections with extreme precision (when the last few hundredths of a millimeter [or thousandths of an inch] of runout must be manually eliminated).

The non-self-centering action of the independent jaws makes centering highly controllable (for an experienced user), but at the expense of speed and ease.

The primary purpose of six- and eight-jawed chucks is to hold thin-walled tubing with minimum deformation.

Two-jaw chucks are available and can be used with soft jaws (typically an aluminium alloy) that can be machined to conform to a particular workpiece.

An alternative collet design is one that has several tapered steel blocks (essentially tapered gauge blocks) held in circular position (like the points of a star, or indeed the jaws of a jawed chuck) by a flexible binding medium (typically synthetic or natural rubber).

(The axial movement of cones is not mandatory, however; a split bushing squeezed radially with a linear force—e.g., set screw, solenoid, spring clamp, pneumatic or hydraulic cylinder—achieves the same principle without the cones; but concentricity can only be had to the extent that the bushing's diameters are perfect for the particular object being held.

One of the corollaries of the conical action is that collets may draw the work axially a slight amount as they close.

Two sprung balls fit into closed grooves, allowing movement whilst retaining the bit.

In essence, each jaw is one independent CNC axis, a machine slide with a leadscrew, and all four or six of them can act in concert with each other.

Electromagnets or permanent magnets are brought into contact with fixed ferrous plates, or pole pieces, contained within a housing.

[9] A vacuum chuck is primarily used on non-ferrous materials, such as copper, bronze, aluminium, titanium, plastics, and stone.

In a vacuum chuck, air is pumped from a cavity behind the workpiece, and atmospheric pressure provides the holding force.

The original forms of workholding on lathes were between-centers holding and ad hoc fastenings to the headstock spindle.

Ad hoc fastening methods in centuries past included anything from pinning with clenching or wedging; nailing; lashing with cords of leather or fiber; dogging down (again involving pinning/wedging/clenching); or other types.

[10] By 1807 the word had changed to the more familiar 'chuck: "On the end of the spindle ... is screwed ... a universal Chuck for holding any kind of work".

In late 1818 or early 1819 the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce awarded its silver medal and 10 guineas (£10.50 – equivalent to £1,006 in 2023[12]) to Mr. Alexander Bell for a three jaw lathe chuck:The instrument can be screwed into ... the mandrel of a lathe, and has three studs projecting from its flat surface, forming an equi-lateral triangle, and are capable of being moved equably to, or from, its centre.

[14] In the United States Simon Fairman (1792–1857) developed a recognisable modern scroll chuck as used on lathes.