Church of Ireland

[4] As with other members of the global Anglican communion, individual parishes accommodate differing approaches to the level of ritual and formality, variously referred to as High and Low Church.

[7][incomplete short citation] This makes it both catholic, as the inheritor of a continuous tradition of faith and practice, and protestant, since it rejects the authority of Rome and accepts changes in doctrine and liturgy caused by the Reformation.

[13] Prior to the 12th century, the Irish church was independent[citation needed] of Papal control, and governed by powerful monasteries, rather than bishops.

[15] Under the Laudabiliter in 1155, English-born Pope Adrian IV granted Henry II of England the Lordship of Ireland in return for paying tithes to Rome.

His claim was based on the 4th-century Donation of Constantine, which allegedly gave the Papacy religious control over all Christian territories in the western Roman Empire.

[16] Since Ireland was now considered a papal fief, its bishops were appointed by Rome but generally adopted English liturgy and saints, such as Edward the Confessor, and Thomas Becket.

Largely restricted to Dublin, led by Archbishop George Browne, it expanded under Edward VI, until Catholicism was restored by his sister Mary I in 1553.

Continued by John Kearny and Nehemiah Donnellan, it was finally printed in 1602 by William Daniel, who also translated the Book of Common Prayer, or BCP, in 1606.

Largely confined to an English-speaking minority in The Pale, the most important figure of the Church's development was Dublin-born theologian and historian, James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh from 1625 to 1656.

Rinuccini's insistence on following Roman liturgy, and attempts to re-introduce ceremonies such as foot washing divided the Confederacy, and contributed to its rapid collapse in the 1649–1652 Cromwell's re-conquest of Ireland.

[29] In practice, the penal laws were loosely enforced and after 1666, Protestant Dissenters and Catholics were allowed to resume their seats in the Parliament of Ireland.

In 1685, the Catholic James II became king with considerable backing in all three kingdoms; this changed when his policies seemed to go beyond tolerance for Catholicism and into an attack on the established church.

His prosecution of the Seven Bishops in England for seditious libel in June 1688 destroyed his support base, while many felt James lost his right to govern by ignoring his coronation Oath to maintain the primacy of the Protestant religion.

[30] This made oaths a high-profile issue, since ministers of the national churches of England, Scotland and Ireland were required to swear allegiance to the ruling monarch.

When the 1688 Glorious Revolution replaced James with his Protestant daughter and son-in-law, Mary II and William III, a minority felt bound by their previous oath and refused to swear another.

[31] The Irish church was less affected by this controversy, although the Bishop of Kilmore and Ardagh became a Non-Juror, as did a handful of the clergy, including Jacobite propagandist Charles Leslie.

[34] It is estimated fewer than 15 – 20% of the Irish population were nominally members of the church, which remained a minority under pressure from both Catholics and Protestant Nonconformists.

However, in 1725 Parliament passed the first in a series of 'temporary' Indemnity Acts, which allowed office holders to 'postpone' taking the oaths; the bishops were willing to approve these, since they could be repealed at any point.

[37] After 1750, the government increasingly viewed Catholic emancipation as a way to reduce the power of Protestant nationalists like the United Irishmen; this had potential implications for the church since the requirement non-church members pay tithes was deeply resented.

Compensation was paid but in the immediate aftermath, parishes faced great difficulty in local financing after the loss of rent-generating lands and buildings.

Although he has relatively little absolute authority, the Archbishop of Armagh is respected as the church's general leader and spokesman, and is elected in a process different from those for all other bishops.

Each parish has a presiding member of the clergy, assisted by two churchwardens and often also two glebewardens, one of each type of warden being appointed by the clerical incumbent, and one by popular vote.

Teacher training now occurs within the Dublin City University Institute of Education, overseen by the Church of Ireland Centre, based at the former All Hallows College.

[55] The Church of Ireland was represented at GAFCON III, held on 17–22 June 2018 in Jerusalem, by a six-member delegation which included two bishops; Ferran Glenfield of Kilmore, Elphin and Ardagh and Harold Miller of Down and Dromore.

[59] GAFCON supporters refuted their critics claims, saying that they endorse Lambeth 1.10 resolution on human sexuality, which is still the official stance of the Church of Ireland, but has been rejected by the liberal provinces of the Anglican Communion.

While being clear that participation in its common life is based upon fidelity to the biblical gospel, not merely upon historic ties, the Jerusalem Statement and Declaration of 2008 says quite unequivocally that 'Our fellowship is not breaking away from the Anglican Communion'.

The basic teachings of the church include: The 16th-century apologist, Richard Hooker, posits that there are three sources of authority in Anglicanism: scripture, tradition and reason.

"[78] In 2004, then Archbishop John Neill said that the "Church would support the extension of legal rights on issues such as tax, welfare benefits, inheritance and hospital visits to cohabiting couples, both same gender and others.

[87] When asked about clergy entering into civil same-sex marriages, the letter stated that "all are free to exercise their democratic entitlements once they are enshrined in legislation.

[89] REFORM Ireland, a conservative lobby, has criticised the official letter as "a dangerous departure from confessing Anglicanism" and continues to oppose same-sex marriage recognition.

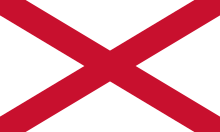

▉ ▉ ▉ Province of Armagh

▉ ▉ ▉ Province of Dublin