Nicotine marketing

This is done through an emphasis on informed choice and "anti-teen-smoking" campaigns,[3]: 198–201 although such ads have been criticized as counterproductive (causing more smoking) by independent groups.

Internal documents also show that the industry used its influence with the media to shape coverage of news, such as a decision not to mandate health warnings on cigarette packages or a debate over advertising restrictions.

[10] The most effective media are usually banned first, meaning advertisers need to spend more money to addict the same number of people.

[3]: 272 Comprehensive bans can make it impossible to effectively substitute other forms of advertising, leading to actual falls in consumption.

Its tagline read "NEVER let the goody two shoes get you down",[11] making use of reactance; it had also been described as urging smokers to disregard health warnings.

[12] The model's gesture in the advert echoed earlier ads which made more explicit claims of voice box benefits.

Some anti-smoking ads dramatise the statistics (e.g. by piling 1200 body bags in front of the New York headquarters of Philip Morris, now Altria, to illustrate the number of people dying daily from smoking);[24] others document individual experiences.

"Roachers", selected for good looks, style, charm,[3]: 110 and being slightly older than the targets,[26] are hired to offer samples of the product.

[3]: 110 "Hipsters" are also recruited clandestinely from the bar and nightclub scene to sell cigarettes, and ads are placed in alternative media publications with "hip credibility".

[3]: 108–110 Other strategies include sponsoring bands and seeking to give an impression of usage by scattering empty cigarette packages.

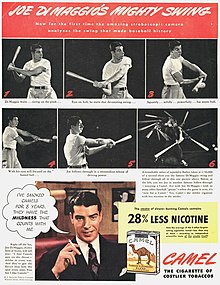

It seeks to associate nicotine use with positive traits, such as intelligence, fun, sexiness, sociability, high social status, wealth, health, athleticism, and pleasant outdoor pursuits.

[37] According to the CDC Tobacco Product Use Among Adults 2015 report, people who are American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic, less-educated (0–12 years education; no diploma, or General Educational Development), lower-income (annual household income <$35,000), the uninsured, and those under serious psychological distress have the highest reported percentage of any tobacco product use.

[41][42] The tobacco industry targeted young rural men by creating advertisements with images of cowboys, hunters, and race car drivers.

[43] The tobacco industry focusses marketing towards vulnerable groups, contributing to the large disparity in smoking and health problems.

[54] To imply that some nicotine products are healthier than others without making explicit claims, marketing has used descriptions like "light", "mild", "natural", "gentle", "calm", "soft", and "smooth".

[21]: 25–27 Historian Keith Wailoo argues the cigarette industry targeted a new market in the black audience starting in the 1960s.

They did this by developing menthol-flavored brands like Kool, which seemed to be more soothing to the throat, as well as advertised them as good for smokers' health.

Big Tobacco responded by investing heavily in the Civil Rights Movement, winning the gratitude of many national and local leaders.

[61] In the fifties, filters were added to cigarettes, and heavily marketed, until they faced regulatory action as false advertising.

[64] According to the US federal government's National Cancer Institute (NCI), light cigarettes provide no benefit to smokers' health.

[72] A 2014 review said, "the e-cigarette companies have been rapidly expanding using aggressive marketing messages similar to those used to promote cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s.

[76] "[A]dvertising for low delivery or traditional brands should be constructed in ways so as not to provoke anxiety about health, but to alleviate it, and enable the smoker to feel assured about the habit and confident in maintaining it over time."

On average, smokers start as adolescents and make over 30 quit attempts, at a rate of about 1 per year, before breaking a nicotine addiction in their 40s or 50s.

Class action plaintiffs and politicians described the Joe Camel images as a "cartoon" intended to advertise the product to people below the legal smoking age.

For instance, Dr. Suresh Kumar Arora, New Delhi's chief tobacco control officer, said: "We were wasting our time fining cigarette vendors and distributors.

Our teams would tear down posters and in no time, they would be up again because the real culprits were the big tobacco companies – ITC, Philip Morris (now Altria), Godfrey Phillip.

[82] Easily circumvented age verification at company websites enables minors to access and be exposed to marketing for e-cigarettes.

The Federal Trade Commission claimed that cigarette manufacturers spent $8.24 billion on advertising and promotion in 1999, the highest amount ever at that time.

[93] Marketing consultants ACNielsen announced that, during the period September 2001 to August 2002, tobacco companies advertising in the UK spent £25 million, excluding sponsorship and indirect advertising, broken down as follows: Figures from around that time also estimated that the companies spent £8m a year sponsoring sporting events and teams (excluding Formula One) and a further £70m on Formula One in the UK.

[73] A 2014 review said, "the e-cigarette companies have been rapidly expanding using aggressive marketing messages similar to those used to promote cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s.