Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

As the Mongols conquered vast regions of Central Asia and the Middle East, Hethum and succeeding Hethumid rulers sought to create an Armeno-Mongol alliance against common Muslim foes, most notably the Mamluks.

[7] In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Crusader states and the Mongol Ilkhanate disintegrated, leaving the Armenian Kingdom without any regional allies.

After relentless attacks by the Mamluks in Egypt in the fourteenth century, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, then under the rule of the Lusignan dynasty and mired in an internal religious conflict, finally fell in 1375.

Many aspects of Western European life were adopted by the nobility including chivalry, fashions in clothing, and the use of French titles, names, and language.

[9] Armenian presence in Cilicia dates back to the first century BC, when under Tigranes the Great, the Kingdom of Armenia expanded and conquered a vast region in the Levant.

In 83 BC, the Greek aristocracy of Seleucid Syria, weakened by a bloody civil war, offered their allegiance to the ambitious Armenian king.

The Caliphate's occupation of Cilicia and of other areas in Asia Minor led many Armenians to seek refuge and protection further west in the Byzantine Empire, which created demographic imbalances in the region.

[12] In order to better protect their eastern territories after their reconquest, the Byzantines resorted largely to a policy of mass transfer and relocation of native populations within the Empire's borders.

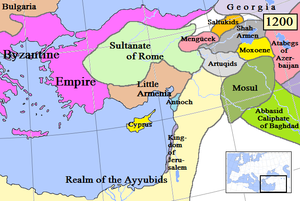

[14] The formal annexation of Greater Armenia to the Byzantine Empire in 1045 and its conquest by the Seljuk Turks 19 years later caused two new waves of Armenian migration to Cilicia.

Following its conquest in 1045, and in the midst of Byzantine efforts to further repopulate the Empire's east, Armenian immigration into Cilicia intensified and turned into a major socio-political movement.

Seven years later, they earned a decisive victory against Byzantium by defeating Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes' army at Manzikert, north of Lake Van.

After Catholicos Gregory II the Martyrophile's assistant and representative, Parsegh of Cilicia's solicitation, the Armenians obtained a partial reprieve, but Malik's succeeding governors continued levying taxes.

Often at the invitation of Armenian barons and kings the Crusaders maintained for varying periods castles in and along the borders of the Kingdom, including Bagras, Trapessac, T‛il Hamtun, Harunia, Selefkia, Amouda, and Sarvandikar.

During this period, there was continued hostility between Cilician Armenia and the Seljuk Turks, as well as occasional bickering between Armenians and the Principality of Antioch over forts located near southern Amanus.

[19] Ruben was blinded and killed while in prison, but Levon's second son and successor, Thoros II, escaped in 1141 and returned to Cilicia to lead the struggle with the Byzantines.

Cilician Armenia's prominence in the region is attested by letters sent in 1189 by Pope Clement III to Levon and to Catholicos Gregory IV, in which he asks Armenian military and financial assistance to the crusaders.

[25] The Rubenids consolidated their power by controlling strategic roads with fortifications that extended from the Taurus Mountains into the plain and along the borders, including the baronial and royal castles at Sis, Anavarza, Vahka, Vaner/Kovara, Sarvandikar, Kuklak, T‛il Hamtun, Hadjin, and Gaban (modern Geben).

[5] In 1219, after a failed attempt by Raymond-Roupen to claim the throne, Levon's daughter Zabel was proclaimed the new ruler of Cilician Armenia and placed under the regency of Adam of Baghras.

In order to enact revenge for his son's death, Bohemond sought an alliance with Seljuk sultan Kayqubad I, who captured regions west of Seleucia.

Despite his sometimes-burdensome military commitments to the Mongols, Het’um had the financial resources and political autonomy to build new and impressive fortifications, such as the castle at Tamrut.

[29] According to Arab historians, during Hulagu's conquest of Aleppo, Het'um and his forces were responsible for a massacre and arsons in the main mosque and in the neighboring quarters and souks.

[27] Cilician Armenia also expanded and recovered lands crossed by important trade routes on the Cappadocian, Mesopotamian, and Syrian borders, including Marash and Behesni, which further made the Armenian Kingdom a potential Mamluk target.

During the Disaster of Mari, the Mamluks under Sultan Al-Mansur Ali and the commander Qalawun overran the heavily outnumbered Armenians, killing T'oros and capturing Levon.

The city of Tarsus was taken, the royal palace and the church of Saint Sophia was burned, the state treasury was looted, 15,000 civilians were killed, and 10,000 were taken captive to Egypt.

In 1303, the Mongols tried to conquer Syria once again in larger numbers (approximately 80,000) along with the Armenians, but they were defeated at Homs on March 30, 1303, and during the decisive Battle of Shaqhab, south of Damascus, on April 21, 1303.

Guy de Lusignan and his younger brother John were considered pro-Latin and deeply committed to the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church in the Levant.

[48] Amidst failed Armenian pleas for help from Europe, the fall of Sis to the Mamluks, followed by the fortress of Gaban in 1375, where King Levon V, his daughter Marie, and her husband Shahan had taken refuge, put an end to the kingdom.

[52] The Cilician period also produced some important examples of Armenian art, notably the illuminated manuscripts of Toros Roslin, who was at work in Hromkla in the thirteenth century.

The three primary harbours of the Armenian Kingdom, which were vital to its economy and defense, were the fortified coastal sites at Ayas and Korikos, and the river emporium of Mopsuestia.

The latter, situated on two strategic caravan routes, was the last fully navigable port to the Mediterranean on the Pyramus River and the location of warehouses licensed by the Armenians to the Genoese.

) clearly visible.

[

42

]

[

43

]

[

44

]

) clearly visible.

[

42

]

[

43

]

[

44

]