Cimoliopterus

The specific name cuvieri honoured the palaeontologist George Cuvier, and the genus Pterodactylus was then used for many pterosaurs of species that are no longer thought to be closely related.

While long considered an ornithocheiran, the affinities of C. cuvieri were unclear due to the fragmentary nature of it and other English pterosaurs, until more complete relatives were reported from Brazil in the 1980s.

[4] In 1851, the British naturalist James Scott Bowerbank described a large pterosaur snout he had obtained, which was found in the Lower Culand Pit in what is now called the Grey Chalk Subgroup at Burham, Kent, in South East England.

Pterosaur fossils had been discovered earlier in the same pit, including the front part of some jaws Bowerbank had used as the basis for the species Pterodactylus giganteus in 1846, as well as other bones.

[11][12] In the 1850s the British artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins created full-sized sculptures of prehistoric animals for Crystal Palace Park in London, under the supervision of Owen.

Witton and the British biologist Ellinor Michel said in 2023 that while it was the largest known pterosaur at the time, its historical significance was overshadowed by the 1870 discovery of the larger Pteranodon, a genus that was widely featured in text and artwork, while the Crystal Palace sculptures remained the only major publicity of P.

[9] In 1869, the British palaeontologist Harry Govier Seeley placed P. cuvieri in the new genus Ptenodactylus along with other English pterosaurs known mainly from upper jaws, in an index of specimens in the Woodwardian Museum.

[20] In 1922, the Austrian naturalist Gustav von Arthaber lamented that the scientific literature had accepted the many Ornithocheirus names that had only been mentioned in Seeley's catalogue for students.

[24] In 1991, Wellnhofer stated that the genus Ornithocheirus had become a "wastebin" of species from different countries, assigned to it on the basis of insufficient characters, and needed clearer definition, and perhaps included several distinct genera.

[25] The British palaeontologist S. Christopher Bennett stated in 1993 that the holotype specimen of O. cuvieri was the right first wing-phalanx bone mentioned by Owen in 1851, and cited him for the name without further explanation.

Rodrigues and Kellner also found that while the species P. fittoni, O. brachyrhinus, and O. enchorhynchus had various features in common with C. cuvieri, and could therefore not be excluded from that genus, they were too fragmentary to be assigned to it definitively and were considered nomina dubia (dubious names).

[31][9] In 2013, the American amateur fossil collector Brent Dunn discovered a pterosaur snout fragment in the Britton Formation near Lewisville Lake, northwest of Dallas, Texas, US.

[35] Rodrigues and Kellner provided a single diagnosis (a list of features distinguishing a taxon from its relatives) for the genus Cimoliopterus and species C. cuvieri in 2013, which Myers amended in 2015 when including C. dunni.

The right of the two frontmost sockets contained a newly erupted (emerged through the gums) tooth, which protruded about one-third of an inch downwards and forwards at an oblique angle.

The height of P. fittoni's snout can be differentiated from that of C. cuvieri, whose tip is also wider than high; the latter difference is possibly due to fracture, though, and the species cannot be unquestionably assigned.

While crest-related features should be used with caution when identifying species, since they can be linked to growth stage or sexual dimorphism, the difference in crest-shape between C. dunni and C. cuvieri is probably unrelated to age, since the holotypes represent similarly sized individuals.

[7] Although Myers found Aetodactylus to be closely related to Cimoliopterus, differences in jaw morphology and orientation and spacing of the tooth sockets indicate they are distinct from each other.

Due to the similarities in the jaw form as well as the dentition of both C. dunni and C. cuvieri, and clear differences from Aetodactylus in these features, Cimoliopterus is unlikely to be a paraphyletic (unnatural) group according to Myers.

[42] In 2019, the British palaeontologist Megan Jacobs and colleagues performed a phylogenetic analysis where they placed both C. cuvieri and C. dunni within the family Ornithocheiridae, as the sister taxon of Camposipterus nasutus.

The cladogram of the phylogenetic analysis by Pêgas and colleagues is presented below on the right, showing the position of Cimoliopterus within Cimoliopteridae, while the other targaryendraconians, Aussiedraco, Barbosania and Targaryendraco, were grouped in Targaryendraconidae.

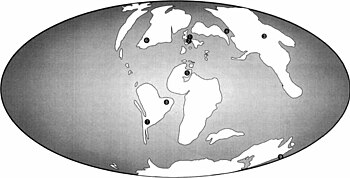

[7] Myers elaborated in a press release that the population ancestral to C. dunni and C. cuvieri was able to move between North America and England until about 94 million years ago, as the similarity between the two species indicated that there had been little time between their divergence.

As the Atlantic opened up the supercontinent Pangaea, populations of animals became isolated from each other, and diverged evolutionarily, but this pattern would have been more complicated with pterosaurs because they could fly across water bodies.

[45] André J. Veldmeijer and colleagues pointed out in 2006 that apart from ornithocheirids usually being found in deposits associated with water, their interlocking teeth also supported piscivory (fish-eating), being built for spearing slippery prey rather than cutting or slashing.

They also pointed out that the differences in crest position, size of the palatinal ridge, and the presence or absence of a front expansion of the jaw, made it hard to believe they all obtained food in the same way, but that this did not rule out some overlap.

They may have hunted small fish or pre-digested them before swallowing (since their teeth were not adapted for chewing), but the second option would have required cheeks or throat pouches to keep prey inside the mouth; the latter has been reported in some pterosaurs.

[47] In 2013, Witton noted the skim-feeding hypothesis for ornithocheirids had been questioned, but that dip-feeding (as seen among terns and frigatebirds) was supported by various features, like their elongated snouts, well-suited for reaching swimming animals, as well as their "fish-grab" tooth arrangement.

[32][50][51] Other animals known from the Grey Chalk Subgroup include pterosaurs such as Lonchodraco and many dubious species, and dinosaurs like the indeterminate nodosaurid Acanthopholis and the hadrosauroid "Iguanodon" hilli.

The formation is part of the Upper Cretaceous Eagle Ford Group, which dates to the middle Cenomanian to late Turonian ages (96–90 million years ago).

The specimen was preserved in a layer of grey marine shale with iron-oxide concretions, and found in the Sciponoceras gracile ammonite zone, situated in the upper–middle part of the Britton Formation, which dates to the late Cenomanian, approximately 94 million years ago.

Abundant fossil remains of ammonites and crustaceans are contained in the dark grey shales in which C. dunni was found, which is consistent with having been deposited in marine shelf environments that were low in energy and poorly oxygenated.