Circuit rider (religious)

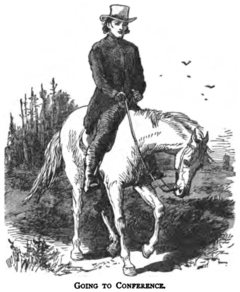

Circuit riders, also known as horse preachers, were clergy assigned to travel around specific geographic territories to minister to settlers and organize congregations.

In sparsely populated areas of the United States it always has been common for clergy in many denominations to serve more than one congregation at a time, a form of church organization sometimes called a "preaching circuit".

In the rough frontier days of the early United States, the pattern of organization in the Methodist Episcopal denomination and its successors worked especially well in the service of rural villages and unorganized settlements.

Early leaders such as Francis Asbury and Richard Whatcoat exercised near total discretion on the selection, training, ordaining, and stationing of circuit riders.

Carrying only what could fit in their saddlebags, they traveled through wilderness and villages, preaching every day at any place available (peoples' cabins, courthouses, fields, meeting houses, even basements and street corners).

Together with his driver and partner "Black Harry" Hosier, he traveled 270,000 miles and preached 16,000 sermons as he made his way up and down early America supervising clergy.

Although John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, covered enormous distances on horseback during his career, and early British Methodist preachers also rode around their circuits, in general they had far less formidable traveling commitments than their American counterparts.

[2] As the United States prospered, there came to be more Methodists living in settled cities with enough population for a proper church building, and less need for the frontier-style camp revivals invoking the Holy Spirit and circuit riders.

Nathan Bangs, a former circuit rider himself in Upper Canada and Quebec, became an influential advocate within Methodism for mature style that eschewed rowdy camp meetings and had educated and middle-class clergy.

While some groups sought to restore the older frontier style, in general Methodism moved beyond circuit riders as their main tool for evangelism.

Brownlow gained wide notoriety for his wild clashes --- both in person and in print --- with rival Baptist and Presbyterian missionaries and Christian sectarian authors across the Southern Appalachian region of the United States.

[11] Brownlow's books detailing the Confederate States of America military occupation of his hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee, and his own time briefly spent in a Confederate prison during the American Civil War gained Brownlow a greatly expanded audience across the northern United States who were eager to purchase both his books and admission tickets for his northern U.S. speaking tour during the later years of the American Civil War.

More than 47 volumes of his personal and business documents are among the Lyman Draper collection at the Wisconsin Historical Society, since they were donated after his death by his son-in-law, Charles H. Constable.

[16] Inspired by the story of Catholic circuit rider Pierre Yves Kéralum, author Paul Horgan wrote a fictionalized account of the priest's last days titled The Devil in the Desert (1952).

[17] The first-person accounts of pioneer circuit riders give insight to the culture of the early United States as well as the theology and sociology of religion (and especially Methodism) in the young nation.