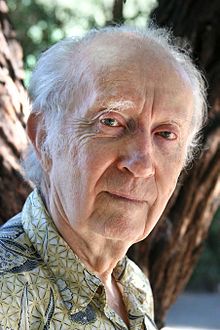

Clare Palmer

Clare Palmer (born 1967) is a British philosopher, theologian and scholar of environmental and religious studies.

She is a former editor of the religious studies journal Worldviews: Environment, Culture, Religion, and a former president of the International Society for Environmental Ethics.

In Environmental Ethics and Process Thinking, which was based on her doctoral research, Palmer explores the possibility of a process philosophy-inspired account of environmental ethics, focussing on the work of Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne.

She ultimately concludes that a process ethic is not a desirable approach to environmental questions, in disagreement with some environmentalist thinkers.

She defends a contextual, relational ethic according to which humans will typically have duties to assist only domestic, and not wild, animals in need.

[2] She graduated from Oxford in 1993 with a doctorate from The Queen's College;[3] her thesis focussed on process philosophy and environmental ethics.

[16] Palmer remained at Stirling for several years before taking up the post of senior lecturer in philosophy at Lancaster University in 2001.

In 2005, she moved to Washington University in St. Louis, where she took up the role of associate professor, jointly appointed in departments of philosophy and environmental studies.

[1] The same year, the five-volume encyclopaedia Environmental Ethics, co-edited by Palmer and J. Baird Callicott, was published by Routledge,[17] and, in the subsequent year, she was part of "The Animal Studies Group" which published the collection Killing Animals with the University of Illinois Press.

[18] While at Washington, she was also the editor of both Teaching Environmental Ethics (Brill, 2007)[19] and Animal Rights (Ashgate Publishing, 2008).

[32] While at Texas A&M, Palmer co-edited the 2011 Veterinary Science: Humans, Animals and Health with Erica Fudge[33] and the 2014 Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World: Values, Philosophy, and Action with Calliott, Ricardo Rozzi, Steward Pickett, and Juan Armesto.

[8] Process thought, Clark notes, has frequently appealed more to theologically inclined environmental ethicists than classical theism; in particular, the views of Hartshorne and Cobb have been influential.

In considering collectivist environmental ethics, Palmer asks how process thinkers could approach natural collectives, such as ecosystems.

All are lacking, she argues, as they are fundamentally capacity-oriented, and thus unable to properly take account of human relationships to animals.

She next identifies different kinds of relations humans may have with animals: affective, contractual and, most significantly, causal.

She then deploys this philosophy in a number of imagined cases in which humans have varying relations to particular animals in need.

She closes the book by considering possible objections, including the idea that her approach would not require someone to save a drowning child at little cost to themselves.

[1] Editorial duties have included acting as an associate editor for Callicott and Robert Frodeman's two-volume encyclopaedia Environmental Philosophy and Ethics and editing the journal Worldviews.