Clark v. Community for Creative Non-Violence

[1] The Community for Creative Non-Violence (CCNV)[2] group had planned to hold a demonstration on the National Mall and Lafayette Park where they would erect tent cities to raise awareness of the situation of the homeless.

[1] The Community for Creative Non-Violence is a group based in Washington D.C., with a mission "to ensure that the rights of the homeless and poor are not infringed upon and that every person has access to life's basic essentials—food, shelter, clothing and medical care".

The Opinion of the Court concluded with: For the foregoing reasons, we find it clear from the Record before us and from the National Park Service's Administrative Policy Statement that these protesters may lawfully sleep in their symbolic campsite.

[7]As a result of the court's decision, CCNV successfully staged its demonstration, including sleeping, for approximately seven weeks during the winter of that year.

They argued that part of the core message the demonstrators wished to convey was that homeless people have no permanent place to sleep.

The protestors choose to sleep, purposely across from the White House and Capitol grounds, in sparsely appointed tents which the Park Service has already designated as undeniably "symbolic."

Their permit application states that this conduct is intended to send the same message as this court recognized was sent in CCNV's 1981-82 demonstration: that the problems of the homeless will not simply disappear into the night.

[14][1][15][16] The Supreme Court issued its decision on June 29, 1984, and in a 7-2 majority vote in favor of the National Park Service, it held that the regulations did not violate the First Amendment.

The Court stressed that expression is subject to reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions, also that the means of the protest went against the government's interest in maintaining the condition of the national parks.

Moreover, the regulation narrowly focuses on the Government's substantial interest in maintaining the parks in the heart of the Capital in an attractive and intact condition, readily available to the millions of people who wish to see and enjoy them by their presence.

The validity of the regulation need not be judged solely by reference to the demonstration at hand, and none of its provisions are unrelated to the ends that it was designed to serve.

And as noted above, there is a substantial Government interest, unrelated to suppression of expression, in conserving park property that is served by the proscription of sleeping.

The courts below accepted that view, and it is not disputed here that the prohibition on camping, and on sleeping specifically, is content-neutral and is not being applied because of disagreement with the message presented.

The restrictions of time, place, and manner can be allowed if they are (a) narrowly tailored (b) serve a substantial governmental interest and (c) there are alternative channels to communicate the information.

Furthermore, although we have assumed for present purposes that the sleeping banned in this case would have an expressive element, it is evident that its major value to this demonstration would be facilitative.

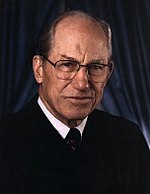

[1]Chief Justice Warren E. Burger delivered a short concurring opinion that he begins by discussing the language of the case "could hardly be plainer in informing the public that camping in Lafayette Park was prohibited.

[20] He took issue with the way in which the majority "misapplies the test for ascertaining whether a restraint on speech qualifies as a reasonable time, place, and manner regulation".

[20] Justice Marshall wrote a detailed case for saying that the sleeping aspect of the demonstration, while overlooked by the majority, was a central part for the homeless cause.

However, for Negroes to stand or sit in a "whites only" library in Louisiana in 1965 was powerfully expressive; in that particular context, those acts became "monuments of protest" against segregation.