Classical Greece

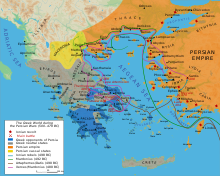

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in ancient Greece,[1] marked by much of the eastern Aegean and northern regions of Greek culture (such as Ionia and Macedonia) gaining increased autonomy from the Persian Empire; the peak flourishing of democratic Athens; the First and Second Peloponnesian Wars; the Spartan and then Theban hegemonies; and the expansion of Macedonia under Philip II.

Much of the early defining mathematics, science, artistic thought (architecture, sculpture), theatre, literature, philosophy, and politics of Western civilization derives from this period of Greek history, which had a powerful influence on the later Roman Empire.

This century is essentially studied from the Athenian outlook because Athens has left us more narratives, plays, and other written works than any of the other ancient Greek states.

Athens' successes caused several revolts among the allied cities, all of which were put down by force, but Athenian dynamism finally awoke Sparta and brought about the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC.

In Ionia (the modern Aegean coast of Turkey), the Greek cities, which included great centres such as Miletus and Halicarnassus, were unable to maintain their independence and came under the rule of the Persian Empire in the mid-6th century BC.

In 480 BC, Darius' successor Xerxes I sent a much more powerful force of 300,000 by land, with 1,207 ships in support, across a double pontoon bridge over the Hellespont.

This army took Thrace, before descending on Thessaly and Boeotia, whilst the Persian navy skirted the coast and resupplied the ground troops.

The subsequent Battle of Artemisium resulted in the capture of Euboea, bringing most of mainland Greece north of the Isthmus of Corinth under Persian control.

[2][3] However, the Athenians had evacuated the city of Athens by sea before Thermopylae, and under the command of Themistocles, they defeated the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis.

In 483 BC, during the period of peace between the two Persian invasions, a vein of silver ore had been discovered in the Laurion (a small mountain range near Athens), and the hundreds of talents mined there were used to build 200 warships to combat Aeginetan piracy.

With the signing of the Thirty Years Peace treaty, Archidamus II felt he had successfully prevented Sparta from entering into a war with its neighbours.

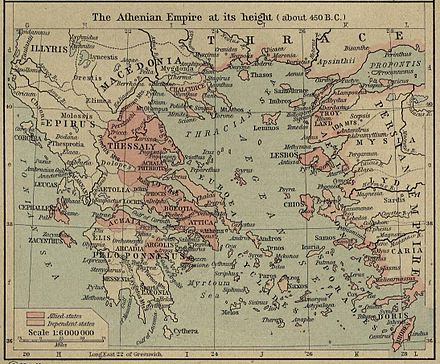

[25] The return of peace allowed Athens to be diverted from meddling in the affairs of the Peloponnesus and to concentrate on building up the empire and putting their finances in order.

[25] A strong "peace party" arose, which promoted avoidance of war and continued concentration on the economic growth of the Athenian Empire.

Enforcement of the economic obligations of the Delian League upon rebellious city-states and islands was a means by which continuing trade and prosperity of Athens could be assured.

Thus, in 415 BC, Alcibiades found support within the Athenian Assembly for his position when he urged that Athens launch a major expedition against Syracuse, a Peloponnesian ally in Sicily, Magna Graecia.

Alcibiades then pursued and met the combined Spartan and Persian fleets at the Battle of Cyzicus later in the spring of 410, achieving a significant victory.

[36] Upon the death of Agis II, Leotychidas attempted to claim the Eurypontid throne for himself, but this was met with an outcry, led by Lysander, who was at the height of his influence in Sparta.

[36] Lysander argued that Leotychidas was a bastard and could not inherit the Eurypontid throne;[36] instead he backed the hereditary claim of Agesilaus, son of Agis by another wife.

The end of the Peloponnesian War left Sparta the master of Greece, but the narrow outlook of the Spartan warrior elite did not suit them to this role.

Athens, Argos, Thebes, and Corinth, the latter two former Spartan allies, challenged Sparta's dominance in the Corinthian War, which ended inconclusively in 387 BC.

With the death of Epaminondas at Mantinea (362 BC) the city lost its greatest leader and his successors blundered into an ineffectual ten-year war with Phocis.

Without the Spartans' support, Lysander's innovations came into effect and brought a great deal of profit for him—on Samos, for example, festivals known as Lysandreia were organized in his honour.

Agesilaus employed a political dynamic that played on a feeling of pan-Hellenic sentiment and launched a successful campaign against the Persian empire.

The Athenians no longer had the means to fulfill their ambitions, and found it difficult merely to finance their own navy, let alone that of an entire alliance, and so could not properly defend their allies.

The confederacy was divided up into 11 districts, each providing a federal magistrate called a "boeotarch", a certain number of council members, 1,000 hoplites and 100 horsemen.

Pelopidas and Epaminondas endowed Thebes with democratic institutions similar to those of Athens, the Thebans revived the title of "Boeotarch" lost in the Persian King's Peace and—with victory at Leuctra and the destruction of Spartan power—the pair achieved their stated objective of renewing the confederacy.

Epaminondas rid the Peloponnesus of pro-Spartan oligarchies, replacing them with pro-Theban democracies, constructed cities, and rebuilt a number of those destroyed by Sparta.

The Spartans were greatly weakened; the Athenians were in no condition to operate their navy, and after 365 no longer had any allies; Thebes could only exert an ephemeral dominance, and had the means to defeat Sparta and Athens but not to be a major power in Asia Minor.

[72] Alexander managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the central Greek city-states, but also to the Persian empire, including Egypt and lands as far east as the fringes of India.

Will Durant wrote in 1939 that "excepting machinery, there is hardly anything secular in our culture that does not come from Greece," and conversely "there is nothing in Greek civilization that doesn't illuminate our own".