Classical Ottoman architecture

The start of the period also coincided with the long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, which is recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.

[4] The 17th century still produced major works such as the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, but the social and political changes of the Tulip Period eventually led to a shift towards Ottoman Baroque architecture.

[15][16][17] The Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul, built between 1500 and 1505, was the culmination of the period of architectural exploration in the late 15th century and was the last step towards the classical Ottoman style.

[2][3] During this period the bureaucracy of the Ottoman state, whose foundations were laid in Istanbul by Mehmet II, became increasingly elaborate and the profession of the architect became further institutionalized.

[22] The long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent is also recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.

[33] The classical period is also notable for the development of Iznik tile decoration in Ottoman monuments, with the artistic peak of this medium beginning in the second half of the 16th century.

He instead experimented with other designs that seemed to aim for a completely unified interior space and for ways to emphasize the visitor's perception of the main dome upon entering a mosque.

The other buildings of the Şehzade Mosque complex include a madrasa, a tabhane, a caravanserai, an imaret, a cemetery with several mausoleums (of varying dates), and a small mektep.

The interior walls of the tomb are entirely covered in extravagant cuerda seca tiles of predominantly green and yellow colours on a dark blue ground, featuring arabesque motifs and inscriptions.

[70][71][72][73] The Sulaymaniyya complex in Damascus is also an important example of a Sinan-designed mosque far from Istanbul, and has local Syrian influences such as the use of ablaq masonry, reused in part from an earlier Mamluk palace.

[71][74] Sinan did not visit Damascus for the project – though he had been there previously with Sultan Selim's army – and the architect in charge of construction work was Mimar Todoros, who most likely used local masons and craftsmen.

[a][77] The Damascus complex is roughly contemporary with the other constructions and renovations that Suleyman ordered further south at the holy sites of Jerusalem, Medina, and Mecca, in which Sinan was generally not involved.

Due to the restricted space, the use of local craftsmen, and its incorporation of the earlier Mamluk-era Palace of Lady Tunshuq, the complex had little resemblance to the classical Ottoman style.

Parts of the complex, including a madrasa and a mosque, are no longer extant today, but the Haseki Sultan Imaret (hospice or soup kitchen) has been preserved.

[86] Inside the city he built the Haseki Hürrem Hamam near Hagia Sophia in 1556–1557, one of the most famous hammams he designed, which includes two equally-sized sections for men and women.

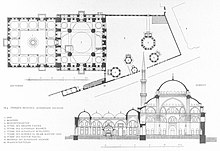

Following the example of the earlier Fatih complex, it consists of many buildings arranged around the main mosque in the center, on a planned site occupying the summit of a hill in Istanbul.

[94] Nonetheless, Sinan employed innovations similar to those he used previously in the Şehzade Mosque: he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of columns and pillars, which allowed for more windows in the walls and minimized the physical separations within the interior of the prayer hall.

[104] Sinan usually kept decoration limited and subordinate to the overall architecture, so this exception is possibly the result of a request by the wealthy patron, grand vizier Rüstem Pasha.

[112] In this mosque Sinan completely integrated the supporting columns of the hexagonal baldaquin into the outer walls for the first time, thus creating a unified interior space.

[115] The mosque's interior is notable for the revetment of Iznik tiles on the wall around the mihrab and on the pendentives of the main dome, creating one of the best compositions of tilework decoration in this period.

The mihrab, carved in marble, is set within a recessed and slightly elevated apse projecting outward from the rest of the mosque, allowing it to be illuminated by windows on three sides.

[155] Across the street from the mosque and madrasa is a structure composed of many courtyards and domed chambers across a large area, which include the tabhane, the imaret, the darüşşifa, and the caravanserai.

[200] One of the most beautiful and famous Ottoman monuments in the Balkans is the single-span bridge known as Stari Most in Mostar (present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina), which was designed or completed by Hayreddin, one of Sinan's assistants.

In addition to the mosque, the complex includes a tabhane, an imaret, a madrasa, a zaviye or khanqah (Sufi lodge), a library, an arasta (market), a caravanserai, and a hammam.

[228] In Razgrad, the Ibrahim Pasha Mosque, constructed in 1616, is interesting for the presence of pointed turrets at the corners of the dome which serve no structural purpose.

The few surviving mosques are often wooden structures with a flat or sloped roof, a single minaret, and sometimes a portico with pointed arches, which seem to mark a local style.

[230][231][232] The relatively small proportion of Muslim inhabitants in Hungary made the commission of extensive religious complexes less necessary, but some madrasas, Sufi tekkes, and hammams are known to have been built.

[253] The most important monument heralding the new Ottoman Baroque style is the Nuruosmaniye Mosque complex, begun by Mahmud I in October 1748 and completed by his successor, Osman III (to whom it is dedicated), in December 1755.

For example, a sense of historicism in Ottoman architecture of the 18th century is evident in Mustafa III's reconstruction of the Fatih Mosque after the 1766 earthquake that partially destroyed it.

[262][263] This mosque is located next to the tomb of Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, an important Islamic religious site in the area of Istanbul originally built by Mehmed II.