Classification of the Indigenous languages of the Americas

The article is divided into North, Central, and South America sections; however, the classifications do not correspond to these divisions.

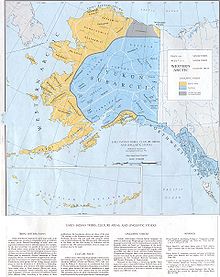

Glottolog 4.1 (2019) recognizes 42 independent families and 31 isolates in North America (73 total).

[1] The vast majority are (or were) spoken in the United States, with 26 families and 26 isolates (52 total).

(Gallatin supported the assimilation of indigenous peoples to Euro-American culture.)

Yuchi John Wesley Powell, an explorer who served as director of the Bureau of American Ethnology, published a classification of 58 "stocks" that is the "cornerstone" of genetic classifications in North America.

John Wesley Powell was in a race with Daniel G. Brinton to publish the first comprehensive classification of North America languages (although Brinton's classification also covered South and Central America).

As a result of this competition, Brinton was not allowed access to the linguistic data collected by Powell's fieldworkers.

Zuñian (=Zuni) Paul Rivet (1924) lists a total of 46 independent language families in North and Central America.

Olive and Janambre are extinct languages of Tamaulipas, Mexico.

Note that Sapir's classification was controversial at the time and it additionally was an original proposal (unusual for general encyclopedias).

Sapir was part of a "lumper" movement in Native American language classification.

Sapir's classifies all the languages in North America into only 6 families: Eskimo–Aleut, Algonkin–Wakashan, Na-Dene, Penutian, Hokan–Siouan, and Aztec–Tanoan.

Sapir's classification (or something derivative) is still commonly used in general languages-of-the-world type surveys.

(Note that the question marks that appear in Sapir's list below are present in the original article.)

Timucua Chumashan, Comecrudan, and Coahuiltecan are included in Hokan with "reservations".

Campbell & Mithun's 1979 classification is more conservative, since it insists on more rigorous demonstration of genetic relationship before grouping.

(preliminary) Families Isolates Stocks The unity of Penutian languages outside Mexico is considered probable by many linguists: Siouan–Yuchi "probable"; Macro-Siouan likely: Natchez–Muskogean most likely of the Gulf hypothesis Hokan: most promising proposals "Unlikely" to be Hokan: Subtiaba–Tlapanec is likely part of Otomanguean (Rensch 1977, Oltrogge 1977).

(Consensus conservative classification) Families Isolates Proposed stocks Notable early classifications of classifications of indigenous South American language families include those by Filippo Salvatore Gilii (1780–84),[4] Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro (1784–87),[5][6] Daniel Garrison Brinton (1891),[7] Paul Rivet (1924),[2] John Alden Mason (1950),[8] and Čestmír Loukotka (1968).

[9] Other classifications include those of Jacinto Jijón y Caamaño (1940–45),[10] Antonio Tovar (1961; 1984),[11][12] and Jorge A. Suárez (1974).

[13][14] Glottolog 4.1 (2019) recognizes 44 independent families and 64 isolates in South America.

Paul Rivet (1924) lists 77 independent language families of South America.

[2] Classification of South American languages by J. Alden Mason (1950):[8] Čestmír Loukotka (1968) proposed a total of 117 indigenous language families (called stocks by Loukotka) and isolates of South America.

Kaufman believes for these 118 units "that there is little likelihood that any of the groups recognized here will be broken apart".

Kaufman puts question marks by Kechumara and Mosetén-Chon stocks.

Kaufman views all of these larger groupings to be hypothetical and his list is to be used as a means to identify which hypotheses most need testing.

Lyle Campbell (2012) proposed the following list of 53 uncontroversial indigenous language families and 55 isolates of South America – a total of 108 independent families and isolates.

Morris Swadesh further consolidated Sapir's North American classification and expanded it to group all indigenous languages of the Americas in just 6 families, 5 of which were entirely based in the Americas.

[17] Joseph Greenberg's classification[18] in his 1987 book Language in the Americas is best known for the highly controversial assertion that all North, Central and South American language families other than Eskimo–Aleut and Na-Dene including Haida, are part of an Amerind macrofamily.

This assertion of only three major American language macrofamilies is supported by DNA evidence,[19] although the DNA evidence does not provide support for the details of his classification.

In American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America, Lyle Campbell describes various pidgins and trade languages spoken by the indigenous peoples of the Americas.