Georges Clemenceau

After a failed love affair, Clemenceau left France for the United States as the imperial agents began cracking down on dissidents and sending most of them to the bagne de Cayennes (Devil's Island Penal System) in French Guiana.

As part of his journalistic activity, Clemenceau covered the country's recovery following the Civil War, the workings of American democracy, and the racial questions related to the end of slavery.

[13][12] From 1876 to 1880, Clemenceau was one of the main defenders of the general amnesty of thousands of Communards, members of the revolutionary government of the 1871 Paris Commune who had been deported to New Caledonia.

From this time, throughout the presidency of Jules Grévy (1879–1887), he became widely known as a political critic and destroyer of ministries (le Tombeur de ministères) who avoided taking office himself.

Leading the far left in the Chamber of Deputies, he was an active opponent of the colonial policy of Prime Minister Jules Ferry, which he opposed on moral grounds and also as a form of diversion from the more important goal of "Revenge against Germany" for the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine after the Franco-Prussian War.

[12] By his exposure of the Wilson scandal, and by his personal plain speaking, Clemenceau contributed largely to the resignation of Jules Grévy from the presidency of France in 1887.

A further misfortune occurred in the Panama affair, as Clemenceau's relations with the businessman and politician Cornelius Herz led to his being included in the general suspicion.

He decided to run the controversial article that would become a famous part of the Dreyfus Affair in the form of an open letter to Félix Faure, the president of France.

Clemenceau sat with the Independent Radicals in the Senate and moderated his positions, although he still vigorously supported the Radical-Socialist ministry of Prime Minister Émile Combes, who spearheaded the anti-clericalist republican struggle.

When French authorities elected to shutter Ahmet Rıza's Meşveret, many journalists, principally Clemenceau, choose to support his efforts against Yıldız's lawsuit.

[16] In March 1906, the ministry of Maurice Rouvier fell as a result of civil disturbances provoked by the implementation of the law on the separation of church and state and the victory of radicals in the French legislative elections of 1906.

[13] The miners strike in the Pas de Calais after the Courrières mine disaster, which resulted in the death of more than one thousand persons, threatened widespread disorder on 1 May 1906.

In response, Clemenceau changed the newspaper's name to L'Homme enchaîné ("The Chained Man") and criticized the government for its lack of transparency and its ineffectiveness, while defending the patriotic union sacrée against the German Empire.

In spite of the censorship imposed by the French government on Clemenceau's journalism at the beginning of World War I, he still wielded considerable political influence.

This forced Alexandre Ribot and Aristide Briand (both the previous two prime ministers, of whom the latter was by far the more powerful politician who had been approached by a German diplomat) to agree in public that there would be no separate peace.

For many years, Clemenceau was blamed for having blocked a possible compromise peace, but it is now clear from examination of German documents that Germany had no serious intention of handing over Alsace-Lorraine.

At home, the government had to deal with increasing demonstrations against the war, a scarcity of resources, and air raids that were causing huge physical damage to Paris as well as undermining the morale of its citizens.

After years of criticism against the French army for its conservatism and Catholicism, Clemenceau would need help to get along with the military leaders to achieve a sound strategic plan.

Clemenceau's war policy encompassed the promise of victory with justice, loyalty to the fighting men, and immediate and severe punishment of crimes against France.

[citation needed] To settle the international political issues left over from the conclusion of World War I, it was decided that a peace conference would be held in Paris, France.

[citation needed] France's leverage was jeopardized repeatedly by Clemenceau's mistrust of Wilson and David Lloyd George, as well as his intense dislike of President Poincaré.

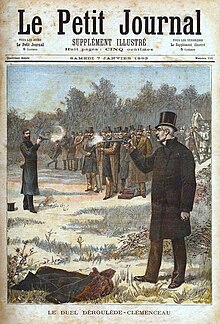

[citation needed] Clemenceau often joked about the "assassin's" bad marksmanship – "We have just won the most terrible war in history, yet here is a Frenchman who misses his target six out of seven times at point-blank range.

Clemenceau replied that the alliance with America and Britain was of more value than an isolated France that held onto the Rhineland: "In fifteen years I will be dead, but if you do me the honour of visiting my tomb, you will be able to say that the Germans have not fulfilled all the clauses of the treaty, and that we are still on the Rhine.

"[42][43] There was increasing discontent among Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Woodrow Wilson about slow progress and information leaks surrounding the Council of Ten.

Lloyd George came to a compromise; the coal mines were given to France and the territory placed under French administration for 15 years, after which a vote would determine whether the region would rejoin Germany.

[44] Although Clemenceau had little knowledge of the defunct Austrian-Hungarian empire, he supported the causes of its smaller ethnic groups and his adamant stance led to the stringent terms in the Treaty of Trianon that dismantled Hungary.

Rather than recognizing territories of the Austrian-Hungarian empire solely within the principles of self-determination, Clemenceau sought to weaken Hungary, just as Germany was, and to remove the threat of such a large power within Central Europe.

Clemenceau was not experienced in the fields of economics or finance, and as John Maynard Keynes pointed out, "he did not trouble his head to understand either the Indemnity or [France's] overwhelming financial difficulties",[45] but he was under strong public and parliamentary pressure to make Germany's reparations bill as large as possible.

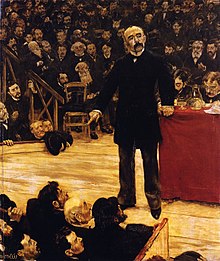

Clemenceau only intervened once in the election campaign, delivering a speech on 4 November at Strasbourg, praising the manifesto and men of the National Bloc and he urged that the victory in the war needed to be safeguarded by vigilance.

For more than a decade, Clemenceau encouraged Monet to complete his donation to the French state of the large Les Nymphéas (Water Lilies) paintings that now are on display in the Paris Musée de l'Orangerie.