Climate of Hawaii

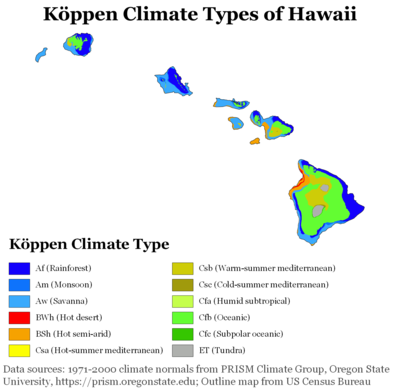

The U.S. state of Hawaiʻi, which covers the Hawaiian Islands, is tropical but it experiences many different climates, depending on altitude and surroundings.

[1] The islands receive most rainfall from the trade winds on their north and east flanks (the windward side) as a result of orographic precipitation.

On Maui, the summit of Haleakalā occasionally experiences snowfall, but snow had never been observed below 7,500 feet (2,300 m) before February 2019, when snow was observed at 6,200 feet (1,900 m) and fell at higher elevations in amounts large enough to force Haleakalā National Park to close for several days.

[6] The Pacific High, and with it the trade-wind zone, moves north and south with changing angle of the sun, so that it reaches its northernmost position in the summer.

Though the trade winds are fairly constant, their relatively uniform air flow is distorted and disrupted by mountains, hills, and valleys.

These are very localized, sometimes reaching speeds of 60 to 100 mph (100 to 160 km/h) and are best known in the settled areas of Kula and Lāhainā on Maui.

The break (a large-scale feature of the Pacific High) is caused by a temperature inversion embedded in the moving trade wind air.

In leeward areas well screened from the trade winds (such as the west coast of Maui), skies are clear 30 to 60 percent of the time.

Windward areas tend to be cloudier during the summer, when the trade winds and associated clouds are more prevalent, while leeward areas, which are less affected by cloudy conditions associated with trade wind cloudiness, tend to be cloudier during the winter, when storm fronts pass through more frequently.

On Maui, the cloudiest zones are at and just below the summits of the mountains, and at elevations of 2,000 to 4,000 ft (600 to 1,200 m) on the windward sides of Haleakalā.

The storms may be associated with the passage of a cold front, the leading edge of a mass of relatively cool air that is moving from west to east or from northwest to southeast.

Severe thunderstorms, as defined by the National Weather Service (NWS) as tornadoes, hail 1 in (25 mm) or larger, and/or convective winds of at least 58 mph (93 km/h) occur but are relatively uncommon.

These storms tend to originate off the coast of Mexico (particularly the Baja California peninsula) and track west or northwest towards the islands.

As storms cross the Pacific, they tend to lose strength if they bear northward and encounter cooler water.

Another hurricane, ʻIwa, caused significant damage in 1982 but its center passed nearby and did not directly make landfall.

In the Pliocene era, where CO2 levels were comparable to those we see today, the waters around Hawaiʻi were much warmer, resulting in frequent hurricane strikes in computer simulations.

[15] Aerodynamic theory indicates that an island wind wake effect should dissipate within a few hundred kilometers and not be felt in the western Pacific.

It is this active interaction between wind, ocean current, and temperature that creates this uniquely long wake west of Hawaiʻi.

The wind wake drives an eastward "counter current" that brings warm water 5,000 miles (8,000 km) from the Asian coast.

This warm water drives further changes in wind, allowing the island effect to extend far into the western Pacific.

The counter current had been observed by oceanographers near the Hawaiian Islands years before the long wake was discovered, but they did not know what caused it.