Clostridioides difficile infection

[1] Antibiotics can contribute to detrimental changes in gut microbiota; specifically, they decrease short-chain fatty acid absorption which results in osmotic, or watery, diarrhea.

[1] Risk factors for infection include antibiotic or proton pump inhibitor use, hospitalization, hypoalbuminemia,[8] other health problems, and older age.

[14] The majority of infections are acquired outside of hospitals, where medications and a recent history of diarrheal illnesses (e.g. laxative abuse or food poisoning due to salmonellosis) are thought to drive the risk of colonization.

[16] In adults, a clinical prediction rule found the best signs to be significant diarrhea ("new onset of more than three partially formed or watery stools per 24-hour period"), recent antibiotic exposure, abdominal pain, fever (up to 40.5 °C or 105 °F), and a distinctive foul odor to the stool resembling horse manure.

Under gram staining, C. difficile cells are gram-positive and show optimum growth on blood agar at human body temperatures in the absence of oxygen.

[20] The risk of colonization has been linked to a history of unrelated diarrheal illnesses (e.g. laxative abuse and food poisoning due to Salmonellosis or Vibrio cholerae infection).

Toxin B (cytotoxin) induces actin depolymerization by a mechanism correlated with a decrease in the ADP-ribosylation of the low molecular mass GTP-binding Rho proteins.

[20] The emergence of a new and highly toxic strain of C. difficile that is resistant to fluoroquinolone antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, said to be causing geographically dispersed outbreaks in North America, was reported in 2005.

[24] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta warned of the emergence of an epidemic strain with increased virulence, antibiotic resistance, or both.

The organism forms heat-resistant spores that are not killed by alcohol-based hand cleansers or routine surface cleaning.

[15] In 2005, molecular analysis led to the identification of the C. difficile strain type characterized as group BI by restriction endonuclease analysis, as North American pulse-field-type NAP1 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and as ribotype 027; the differing terminology reflects the predominant techniques used for epidemiological typing.

[32] Long-term hospitalization or residence in a nursing home within the previous year are independent risk factors for increased colonization.

[36] People with a recent history of diarrheal illness are at increased risk of becoming colonized by C. difficile when exposed to spores, including laxative abuse and gastrointestinal pathogens.

[15] Disturbances that increase intestinal motility are thought to transiently elevate the concentration of available dietary sugars, allowing C. difficile to proliferate and gain a foothold in the gut.

[15] During this time, the abundance of C. difficile varies considerably day-to-day, causing periods of increased shedding that could substantially contribute to community-acquired infection rates.

[15] As a result of suppression of healthy bacteria, via a loss of bacterial food source, prolonged use of an elemental diet increases the risk of developing C. difficile infection.

[44] The use of systemic antibiotics, including broad-spectrum penicillins/cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin, causes the normal microbiota of the bowel to be altered.

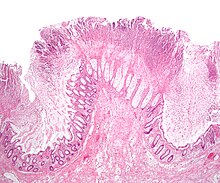

Although colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy are still employed, now stool testing for the presence of C. difficile toxins is frequently the first-line diagnostic approach.

[51][52] Not testing for both may contribute to a delay in obtaining laboratory results, which is often the cause of prolonged illness and poor outcomes.

[55] The screening specificity is relatively low because of the high number of false positive cases from asymptomatic infection.

Further, reactions to medication may be severe: CDI infections were the most common contributor to adverse drug events seen in U.S. hospitals in 2011.

[64] One study in particular found that there does appear to be a "protective effect" of probiotics, specifically reducing the risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) by 51% in 3,631 outpatients, but it is important to note that the types of infections in the subjects were not specified.

[66] Infection control measures, such as wearing gloves and noncritical medical devices used for a single person with CDI, are effective at prevention.

Ultraviolet cleaning devices, and housekeeping staff especially dedicated to disinfecting the rooms of people with C. difficile after discharge may be effective.

[48] Cholestyramine, an ion-exchange resin, is effective in binding both toxin A and B, slowing bowel motility, and helping prevent dehydration.

[88][89][90] It involves infusion of the microbiota acquired from the feces of a healthy donor to reverse the bacterial imbalance responsible for the recurring nature of the infection.

[citation needed] However, in laboratory settings paired isolates can be differentiated using Whole-Genome Sequencing or Multilocus Variable-Number Tandem-Repeat Analysis.

[81] For patients with C. diff infections that fail to be resolved with traditional antibiotic regimens, fecal microbiome transplants boasts an average cure rate of >90%.

Fecal microbiota transplant may expedite this recovery by directly replacing the missing microbial community members.

"[107] Ivan C. Hall and Elizabeth O'Toole first named the bacterium Bacillus difficilis in 1935, choosing its specific epithet because it was resistant to early attempts at isolation and grew very slowly in culture.