Coal ball

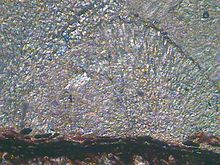

Coal balls often preserve a remarkable record of the microscopic tissue structure of Carboniferous swamp and mire plants, which would otherwise have been completely destroyed.

Their unique preservation of Carboniferous plants makes them valuable to scientists, who cut and peel the coal balls to research the geological past.

The oldest known coal balls date from the Namurian stage of the Carboniferous; they were found in Germany and on the territory of former Czechoslovakia.

[2] Noé's work renewed interest in coal balls, and by the 1930s had drawn paleobotanists from Europe to the Illinois Basin in search of them.

[13] Some supporters of the in situ theory believe that Stopes' and Watson's discovery of a plant stem extending through multiple coal balls shows that coal balls formed in situ, stating that the drift theory fails to explain Stopes' and Watson's observation.

Coal balls are calcium-rich permineralised life forms,[21] mostly containing calcium and magnesium carbonates, pyrite, and quartz.

[22][23] Other minerals, including gypsum, illite, kaolinite, and lepidocrocite also appear in coal balls, albeit in lesser quantities.

[20] Coal balls commonly contain dolomites, aragonite, and masses of organic matter at various stages of decomposition.

[38] They have been used to analyse the geographical distribution of vegetation: for example, providing evidence that Ukrainian and Oklahoman plants of the tropical belt were once the same.

[1] Three main factors determine the quality of preserved material in a coal ball: the mineral constituents, the speed of the burial process, and the degree of compression before undergoing permineralisation.

[32] Coal balls were first found in England,[43] and later in other parts of the world, including Australia,[16][44] Belgium, the Netherlands, the former Czechoslovakia, Germany, Ukraine,[45] China,[46] and Spain.

[47] They were also encountered in North America, where they are geographically widespread compared to Europe;[1] in the United States, coal balls have been found from Kansas to the Illinois Basin to the Appalachian region.

[51] The process required cutting a coal ball with a diamond saw, then flattening and polishing the thin section with an abrasive.

[53] Although the process could be done with a machine, the large amount of time needed and the poor quality of samples produced by thin sectioning gave way to a more convenient method.

Shya Chitaley addressed this problem by revising the liquid-peel technique to separate the organic material preserved by the coal ball from the inorganic minerals, including iron sulfide.

Her process essentially entails heating and then making multiple applications of solutions of paraffin in xylene to the coal ball.