Scattering

In physics, scattering is a wide range of physical processes where moving particles or radiation of some form, such as light or sound, are forced to deviate from a straight trajectory by localized non-uniformities (including particles and radiation) in the medium through which they pass.

[3] Near the end of the 19th century, the scattering of cathode rays (electron beams)[4] and X-rays[5] was observed and discussed.

With the discovery of subatomic particles (e.g. Ernest Rutherford in 1911[6]) and the development of quantum theory in the 20th century, the sense of the term became broader as it was recognized that the same mathematical frameworks used in light scattering could be applied to many other phenomena.

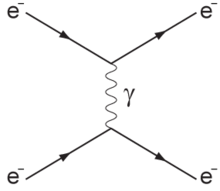

Scattering can refer to the consequences of particle-particle collisions between molecules, atoms, electrons, photons and other particles.

The effects of such features on the path of almost any type of propagating wave or moving particle can be described in the framework of scattering theory.

[12] Because the location of a single scattering center is not usually well known relative to the path of the radiation, the outcome, which tends to depend strongly on the exact incoming trajectory, appears random to an observer.

A well-controlled laser beam can be exactly positioned to scatter off a microscopic particle with a deterministic outcome, for instance.

Such situations are encountered in radar scattering as well, where the targets tend to be macroscopic objects such as people or aircraft.

In certain rare circumstances, multiple scattering may only involve a small number of interactions such that the randomness is not completely averaged out.

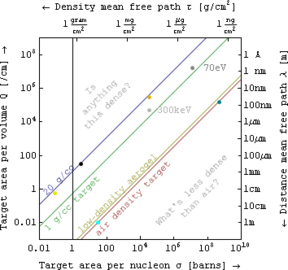

The above ordinary first-order differential equation has solutions of the form: where Io is the initial flux, path length Δx ≡ x − xo, the second equality defines an interaction mean free path λ, the third uses the number of targets per unit volume η to define an area cross-section σ, and the last uses the target mass density ρ to define a density mean free path τ.

In nuclear physics, area cross-sections (e.g. σ in barns or units of 10−24 cm2), density mean free path (e.g. τ in grams/cm2), and its reciprocal the mass attenuation coefficient (e.g. in cm2/gram) or area per nucleon are all popular, while in electron microscopy the inelastic mean free path[14] (e.g. λ in nanometers) is often discussed[15] instead.

The example of scattering in quantum chemistry is particularly instructive, as the theory is reasonably complex while still having a good foundation on which to build an intuitive understanding.

Thus, for example, the hydrogen atom corresponds to a solution to the Schrödinger equation with a negative inverse-power (i.e., attractive Coulombic) central potential.

An important, notable development is the inverse scattering transform, central to the solution of many exactly solvable models.

The solutions of interest describe the long-term motion of free atoms, molecules, photons, electrons, and protons.

There are two predominant techniques of finding solutions to scattering problems: partial wave analysis, and the Born approximation.

Light scattering is one of the two major physical processes that contribute to the visible appearance of most objects, the other being absorption.

[17][18] Models of light scattering can be divided into three domains based on a dimensionless size parameter, α which is defined as:

In this size regime, the exact shape of the scattering center is usually not very significant and can often be treated as a sphere of equivalent volume.

[19] The degree of scattering varies as a function of the ratio of the particle diameter to the wavelength of the radiation, along with many other factors including polarization, angle, and coherence.

In the Mie regime, the shape of the scattering center becomes much more significant and the theory only applies well to spheres and, with some modification, spheroids and ellipsoids.

The most common are finite-element methods which solve Maxwell's equations to find the distribution of the scattered electromagnetic field.

Sophisticated software packages exist which allow the user to specify the refractive index or indices of the scattering feature in space, creating a 2- or sometimes 3-dimensional model of the structure.

For relatively large and complex structures, these models usually require substantial execution times on a computer.

[21] Electrophoretic light scattering involves passing an electric field through a liquid which makes particles move.