Cocoliztli epidemics

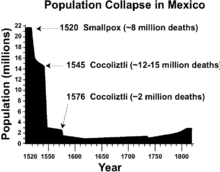

The Cocoliztli Epidemic or the Great Pestilence[1] was an outbreak of a mysterious illness characterized by high fevers and bleeding which caused 5–15 million deaths in New Spain during the 16th century.

[7] Soto et al. have hypothesized that a sizeable hemorrhagic fever outbreak could have contributed to the earlier collapse of the Classic Mayan civilization (AD 750–950).

[12] Accounts by Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, an early Spanish missionary, seem to contradict Ortiz’s sentiment by suggesting that 60–90% of New Spain's total population decreased, regardless of ethnicity.

[13] One noteworthy European casualty of cocoliztli was Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish clergyman and author of the Florentine Codex, who contracted the disease in 1546.

Following the conquest, the Spanish colonists forced the Aztecs and other Indigenous peoples onto easily governable reducciones (congregations) that focused on agricultural production and conversion to Christianity.

The outbreak seemed to be limited to higher elevations, as it was nearly absent from coastal regions at sea level, e.g., the plains along the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific coast.

[5][19][25] According to Francisco Hernández de Toledo, a physician who witnessed the outbreak in 1576, symptoms included high fever, severe headache, vertigo, black tongue, dark urine, dysentery, severe abdominal and chest pain, head and neck nodules, neurological disorders, jaundice, and profuse bleeding from the nose, eyes, and mouth.

This is because cocoliztli, and other diseases that work rapidly, usually do not leave impacts (lesions) on the decedent's bones, despite causing significant damage to the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and other bodily systems.

[19] In 1970, a historian named Germaine Somolinos d'Ardois looked systematically at the proposed explanations, including hemorrhagic influenza, leptospirosis, malaria, typhus, typhoid, and yellow fever.

[25] According to Somolinos d'Ardois, none of these quite matched the 16th-century accounts of cocoliztli, leading him to conclude the disease was a result of a "viral process of hemorrhagic influence."

[30] Marr and Kiracofe attempted to build off this work by reexamining Hernandez's account of cocoliztli and comparing them with various clinical descriptions of other diseases.

[27] In 2018, Johannes Krause, an evolutionary geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, and colleagues discovered new evidence for an Old World culprit.

DNA samples from the teeth of 29 sixteenth-century skeletons in the Oaxaca region of Mexico were identified as belonging to a rare strain of the bacterium Salmonella enterica (subsp.

The researchers recognized nonlocal microbial infections using the MEGAN alignment tool (MALT), a program that attempts to match fragments of extracted DNA with a database of bacterial genomes.

[35] Infections are primarily limited to developing nations in Africa and Asia, although enteric fevers, in general, are still a health threat worldwide.

Generations of contact with the strain likely aided those who unknowingly carried the bacteria, as it is believed that S. Paratyphi C may have first transferred over to humans from swine in the Old World during or shortly after the Neolithic period.

[26] Estimates for the entire number of human lives lost during this epidemic have ranged from 5 to 15 million people,[2] making it one of the most deadly disease outbreaks of all time.

[43] Starting around the end of the outbreak in 1549, the encomederos, impacted by the loss in profits resulting and unable to meet the demands of New Spain, were forced to comply with the new tasaciones (regulations).

[42] The new ordinances, known as Leyes Nuevas, aimed to limit the amount of tribute encomenderos could demand while also prohibiting them from exercising absolute control over the labor force.

This developed into implementing the repartimiento system, which sought to institute a higher level of oversight within the Spanish colonies and maximize the overall tribute extracted for public and crown use.