Cold fusion

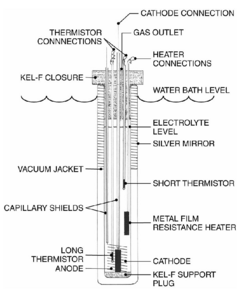

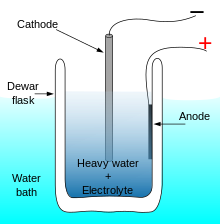

[30] To investigate, they conducted electrolysis experiments using a palladium cathode and heavy water within a calorimeter, an insulated vessel designed to measure process heat.

[33] In mid-March 1989, both research teams were ready to publish their findings, and Fleischmann and Jones had agreed to meet at an airport on 24 March to send their papers to Nature via FedEx.

The 1986 discovery of high-temperature superconductivity had made scientists more open to revelations of unexpected but potentially momentous scientific results that could be replicated reliably even if they could not be explained by established theories.

[39] In the press conference, Chase N. Peterson, Fleischmann and Pons, backed by the solidity of their scientific credentials, repeatedly assured the journalists that cold fusion would solve environmental problems, and would provide a limitless inexhaustible source of clean energy, using only seawater as fuel.

[41] In the accompanying press release Fleischmann was quoted saying: "What we have done is to open the door of a new research area, our indications are that the discovery will be relatively easy to make into a usable technology for generating heat and power, but continued work is needed, first, to further understand the science and secondly, to determine its value to energy economics.

Nathan Lewis, professor of chemistry at the California Institute of Technology, led one of the most ambitious validation efforts, trying many variations on the experiment without success,[44] while CERN physicist Douglas R. O. Morrison said that "essentially all" attempts in Western Europe had failed.

[46][47] Another attempt at independent replication, headed by Robert Huggins at Stanford University, which also reported early success with a light water control,[48] became the only scientific support for cold fusion in 26 April US Congress hearings.

[6] The University of Utah asked Congress to provide $25 million to pursue the research, and Pons was scheduled to meet with representatives of President Bush in early May.

[64] The panel noted the large number of failures to replicate excess heat and the greater inconsistency of reports of nuclear reaction byproducts expected by established conjecture.

Nuclear fusion of the type postulated would be inconsistent with current understanding and, if verified, would require established conjecture, perhaps even theory itself, to be extended in an unexpected way.

[73] An A&M cold fusion review panel found that the tritium evidence was not convincing and that, while they couldn't rule out spiking, contamination and measurements problems were more likely explanations,[text 4] and Bockris never got support from his faculty to resume his research.

On 30 June 1991, the National Cold Fusion Institute closed after it ran out of funds;[74] it found no excess heat, and its reports of tritium production were met with indifference.

[81] After 1991, cold fusion research only continued in relative obscurity, conducted by groups that had increasing difficulty securing public funding and keeping programs open.

These small but committed groups of cold fusion researchers have continued to conduct experiments using Fleischmann and Pons electrolysis setups in spite of the rejection by the mainstream community.

[87] The researchers who continue their investigations acknowledge that the flaws in the original announcement are the main cause of the subject's marginalization, and they complain of a chronic lack of funding[88] and no possibilities of getting their work published in the highest impact journals.

[90] In 1994, David Goodstein, a professor of physics at Caltech, advocated increased attention from mainstream researchers and described cold fusion as: A pariah field, cast out by the scientific establishment.

Cold fusion papers are almost never published in refereed scientific journals, with the result that those works don't receive the normal critical scrutiny that science requires.

[38]United States Navy researchers at the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center (SPAWAR) in San Diego have been studying cold fusion since 1989.

[93] This was thanks to an April 2003 letter sent by MIT's Peter L. Hagelstein,[94]: 3 and the publication of many new papers, including the Italian ENEA and other researchers in the 2003 International Cold Fusion Conference,[95] and a two-volume book by U.S. SPAWAR in 2002.

[104][105] Since the Fleischmann and Pons announcement, the Italian national agency for new technologies, energy and sustainable economic development (ENEA) has funded Franco Scaramuzzi's research into whether excess heat can be measured from metals loaded with deuterium gas.

The Fleischmann and Pons early findings regarding helium, neutron radiation and tritium were never replicated satisfactorily, and its levels were too low for the claimed heat production and inconsistent with each other.

The classical branching ratio for previously known fusion reactions that produce tritium would predict, with 1 watt of power, the production of 1012 neutrons per second, levels that would have been fatal to the researchers.

[124][125] Several medium and heavy elements like calcium, titanium, chromium, manganese, iron, cobalt, copper and zinc have been reported as detected by several researchers, like Tadahiko Mizuno or George Miley.

[130] The 2004 DOE panel expressed concerns about the poor quality of the theoretical framework cold fusion proponents presented to account for the lack of gamma rays.

[139] This was also the belief of geologist Palmer, who convinced Steven Jones that the helium-3 occurring naturally in Earth perhaps came from fusion involving hydrogen isotopes inside catalysts like nickel and palladium.

[140] This led their team in 1986 to independently make the same experimental setup as Fleischmann and Pons (a palladium cathode submerged in heavy water, absorbing deuterium via electrolysis).

[text 12][notes 6] The lack of a shared set of unifying concepts and techniques has prevented the creation of a dense network of collaboration in the field; researchers perform efforts in their own and in disparate directions, making the transition to "normal" science more difficult.

[179] An ACS program chair, Gopal Coimbatore, said that without a proper forum the matter would never be discussed and, "with the world facing an energy crisis, it is worth exploring all possibilities.

Researchers working at the U.S. Navy's Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center (SPAWAR) reported detection of energetic neutrons using a heavy water electrolysis setup and a CR-39 detector,[16][115] a result previously published in Naturwissenschaften.

[124][125] Although details have not surfaced, it appears that the University of Utah forced the 23 March 1989 Fleischmann and Pons announcement to establish priority over the discovery and its patents before the joint publication with Jones.