Colonial Venezuela

Spain established its first permanent South American settlement in the present-day city of Cumaná in 1502, and in 1577 Caracas became the capital of the Province of Venezuela.

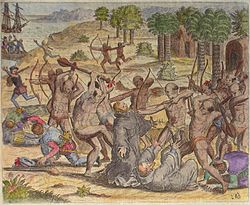

Spain's colonization of mainland Venezuela started in 1502 when it established its first permanent South American settlement in the present-day city of Cumaná (then called Nueva Toledo), which was founded officially in 1515 by Franciscan friars.

At the time of the Spanish arrival (Pre-Columbian period in Venezuela), indigenous people lived mainly in groups as agriculturists and hunters: along the coast, in the Andean mountain range, and along the Orinoco River.

Klein-Venedig (Little Venice) was the most significant part of the German colonization of the Americas, from 1528 to 1546, in which the Augsburg-based Welser banking family obtained colonial rights in Venezuela Province in return for debts owed by Charles I of Spain.

The Viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru (located on the sites formerly occupied by the capital cities of the Aztecs and Incas respectively) showed more interest in their nearby gold- and silver-mines than in the remote agricultural societies of Venezuela.

In the 18th century a second Venezuelan society formed along the coast with the establishment of cocoa plantations manned by much larger importations of African slaves.

Most of the Amerindians who still survived had perforce migrated to the plains and jungles to the south, where only Spanish friars took an interest in them — especially the Franciscans or Capucins, who compiled grammars and small lexicons for some of their languages.

The Guipuzcoana company stimulated the Venezuelan economy, especially in fostering the cultivation of cacao beans, which became Venezuela's principal export.

In Chacao, a town to the east of Caracas, there flourished a school of music whose director José Ángel Lamas (1775–1814) produced a few but impressive compositions according with the strictest 18th-century European canons.

[citation needed] The colony had more external sources of information than other more "important" Spanish dependencies, not excluding the viceroyalties, although one should not belabor this point, for only the mantuanos (a Venezuelan name for the white Creole elite) had access to a solid education.

The general Francisco de Miranda hero of French Revolution has long been associated with the struggle of the Spanish colonies in Latin America for independence.

Miranda envisioned an independent empire consisting of all the territories that had been under Spanish and Portuguese rule, stretching from the Mississippi River to Cape Horn.

In November 1805, Miranda travelled to New York, where privately began organizing a filibustering expedition to liberate Venezuela.

Miranda hired a ship of 20 guns, which he rebaptized Leander in honor of his oldest son, and set sail to Venezuela on 2 February 1806 but failed in an attempt of landing in Ocumare de la Costa.

The Napoleonic Wars in Europe not only weakened Spain's imperial power, but also put Britain (unofficially) on the side of the independence movement.

(At this battle Pablo Morillo, future commander of the army that invaded New Granada and Venezuela; Emeterio Ureña, an anti-independence officer in Venezuela; and José de San Martín, the future Liberator of Argentina and Chile, fought side by side against the French General Pierre Dupont.)

Here the Supreme Central Junta dissolved itself and set up a five-person regency to handle the affairs of state until the full Cortes of Cádiz could convene.

Word of these events soon reached Caracas, but only on 19 April 1810 did its "cabildo" (city council) decide to follow the example set by the Spanish provinces two years earlier, declaring the First Republic of Venezuela.