Comet Kohoutek

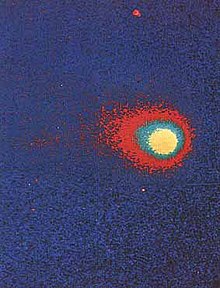

The significant presence of gasses and plasma expelled from Kohoutek supported the longstanding "dirty snowball" hypothesis concerning the composition of comet nuclei.

The object remained evident and was displaced slightly towards the west-northwest in the latter plate, confirming that it was moving against the background stars and not a transient or erroneous feature.

Using the Hamburg Observatory's Schmidt camera, the initial search in October and November 1971 found 52 minor planets in a roughly 180-square-degree region of the sky.

[25][26] Both the Minor Planet Center and the JPL Small-Body Database list Kohoutek as having a hyperbolic trajectory when it was near perihelion,[5][6] but the orbit became bound to the Sun by 1978.

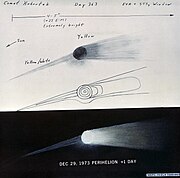

After being positioned in Hydra upon the time of discovery, Comet Kohoutek moved across the constellations of Sextans, Leo, Crater, Corvus, Virgo, Libra, Scorpius, and Sagittarius by the end of 1973.

The tail lacked color closer to the coma near perihelion, indicating a large distribution of particle sizes and resulting in a white appearance.

[37][46] Analyses of Kohoutek's coma and tail in the near-ultraviolet found the roughly equal presence of hydrogen atoms and hydroxide, suggesting that these chemical species were once constituents of water.

[57] The nucleus may also have been once covered by a roughly meter-thick layer of highly volatile substances that quickly outgassed when Kohoutek first approached the inner Solar System.

[58] Radio and microwave observations of the comet identified hydrogen cyanide, methylidyne radicals, and ethyl alcohol in addition to hydroxide and water.

[62][63] Unlike in previously observed comets, the cyano radicals and diatomic carbon in Kohoutek's coma were not distributed spherically but instead elongated significantly away from the sun to distances of up to 10,000,000 km (6,200,000 mi).

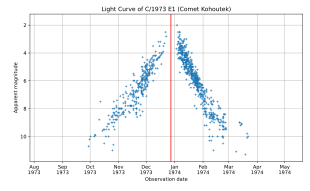

[74] British Astronomical Association (BAA) circular 548, published on 25 July 1973, provided an alternative prediction of magnitude –3 for Kohoutek's peak brightness.

An article in Nature published in the final week of September 1973 suggested that Kohoutek's peak brightness could have a greater than 50 percent chance of being within two magnitudes of –4.

[25] The National Newsletter accompanying the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada in October 1973 estimated that Kohoutek would remain visible to the naked eye for four months bracketing perihelion.

[75][84] The degree of outgassing may have been enhanced by extremely porous outer layers of the nucleus that readily allowed the most volatile ices to vaporize at great distances from the Sun.

The newly built Joint Observatory for Cometary Research near Socorro, New Mexico, was made operational in time to observe the comet.

[90] As a result, a substantial observation program targeting Kohoutek was appended to the original Skylab 4 mission, with the launch date selected due to scientific interest in the comet.

[96] Mariner 10, en route to Venus, also made ultraviolet measurements of Kohoutek at a distance of around 0.7 AU in January 1974,[55][97] making the comet the first to be observed by an interplanetary spacecraft.

[64] Although the comet's unexpected faintness prevented clear television images from being obtained by the spacecraft, Mariner 10's ultraviolet spectrometer nonetheless collected useful data concerning Kohoutek's hydrogen coma.

[99] The results of the observations conducted as part of Operation Kohoutek were presented in June 1974 at a workshop held at the Marshall Space Flight Center.

[15] The media attention was brought about by a combination of factors, including the early predictions of its brightness, its passage concurrent with the Christmas and holiday season, the involvement of many observatories and powerful telescopes, and the possible effort of a crewed spaceflight mission – Skylab 4 – to investigate the comet.

[16][108] NASA also pursued an extensive public relations campaign that led to widespread coverage of the comet's approach in American newspapers in the final six months of 1973.

[16] Dale D. Myers, the Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight at NASA, commented in July 1973 that "comets [of Kohoutek's] size come this close once in a century," further adding to the public interest.

[16][13] On the 30 July 1973 edition of the New York Times, columnist William Safire wrote that Kohoutek "may well be the biggest, brightest, most spectacular astral display that living man has ever seen".

NASA's decision to postpone the launch of Skylab 4 to support observations of the comet only further intensified public interest and added to the attention of the press towards Kohoutek after 16 August 1973.

Although a spokesman for the Goddard Space Flight Center later stated that Kohoutek was a "roaring success" for science, "from a public relations point of view, it [was] a disaster.

[109][112][113] In his final autobiography, Asimov later wrote that "even if it hadn't been [cloudy and rainy every night], Comet Kohoutek proved a colossal disappointment.

[122] In 1973, David Berg, founder of the Children of God, predicted that Comet Kohoutek foretold a colossal doomsday event in the United States by the end of January 1974 because of divine judgment and "America's wickedness".

[120] There were other circulated fringe claims predicting that the comet would cause mass hysteria or spell death for humanity by igniting the global oil supply.

For instance, the Chicago Tribune featured a satirical article linking the optimistic brightness predictions to an effort to distract the public from the Watergate scandal or to a conspiracy to boost telescope sales.

[119]: 7 References to Kohoutek permeated other forms of popular media, such as in the comic strip Peanuts over a week-long period,[119]: 7 in the sitcom El Chavo del Ocho, and a poem by Jaime Sabines.