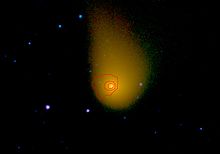

Comet nucleus

The nucleus is the solid, central part of a comet, formerly termed a dirty snowball or an icy dirtball.

[3][4] Further, the ALICE spectrograph on Rosetta determined that electrons (within 1 km (0.62 mi) above the comet nucleus) produced from photoionization of water molecules by solar radiation, and not photons from the Sun as thought earlier, are responsible for the degradation of water and carbon dioxide molecules released from the comet nucleus into its coma.

Even current giant telescopes would give just a few pixels on target, assuming nuclei were not obscured by comae when near Earth.

The "flying sandbank" model, first proposed in the late-1800s, posits a comet as a swarm of bodies, not a discrete object at all.

Whipple argued that a gentle thrust from asymmetric emissions (now "nongravitational forces") better explained comet timing.

[25] The Halley results exceeded even these—comets are not merely dark, but among the darkest objects in the Solar System [26] Furthermore, prior dust estimates were severe undercounts.

[35] Manx comets, Damocloids, and active asteroids demonstrate that there may be no bright line separating the two categories of objects.

Comets, or their precursors, formed in the outer Solar System, possibly millions of years before planet formation.

[38] How and when comets formed is debated, with distinct implications for Solar System formation, dynamics, and geology.

Three-dimensional computer simulations indicate the major structural features observed on cometary nuclei can be explained by pairwise low velocity accretion of weak cometesimals.

[39][40] The currently favored creation mechanism is that of the nebular hypothesis, which states that comets are probably a remnant of the original planetesimal "building blocks" from which the planets grew.

[41][42][43] Astronomers think that comets originate in the Oort cloud, the scattered disk,[44] and the outer Main Belt.

[51] Hale-Bopp appeared bright to the unaided eye because its unusually large nucleus gave off a great deal of dust and gas.

These comets release gas only when holes in this crust rotate toward the Sun, exposing the interior ice to the warming sunlight.

[68] The composition of water vapor from Churyumov–Gerasimenko comet, as determined by the Rosetta mission, is substantially different from that found on Earth.

[69][70] "Missing Carbon"[71][72] On 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko comet, some of the resulting water vapour may escape from the nucleus, but 80% of it recondenses in layers beneath the surface.

[85] Comets are suspected of splitting due to thermal stress, internal gas pressure, or impact.

Numerical integrations have shown that both comets had a rather close approach to Jupiter in January 1850, and that, before 1850, the two orbits were nearly identical.

Solar heating drives off volatile compounds leaving behind heavy long-chain organics that tend to be very dark, like tar or crude oil.

[90][91] During its flyby, Giotto was hit at least 12,000 times by particles, including a 1-gram fragment that caused a temporary loss of communication with Darmstadt.

[90] Halley was calculated to be ejecting three tonnes of material per second[92] from seven jets, causing it to wobble over long time periods.

[3][4] Further, the ALICE spectrograph on Rosetta determined that electrons (within 1 km (0.62 mi) above the comet nucleus) produced from photoionization of water molecules by solar radiation, and not photons from the Sun as thought earlier, are responsible for the degradation of water and carbon dioxide molecules released from the comet nucleus into its coma.