Phobos (moon)

Phobos is named after the Greek god of fear and panic, who is the son of Ares (Mars) and twin brother of Deimos.

It orbits 6,000 km (3,700 mi) from the Martian surface, closer to its primary body than any other known natural satellite to a planet.

As a result, from the surface of Mars it appears to rise in the west, move across the sky in 4 hours and 15 minutes or less, and set in the east, twice each Martian day.

Images and models indicate that Phobos may be a rubble pile held together by a thin crust that is being torn apart by tidal interactions.

Phobos was discovered by the American astronomer Asaph Hall on 18 August 1877 at the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., at about 09:14 Greenwich Mean Time.

[16] The names, originally spelled Phobus and Deimus respectively, were suggested by the British academic Henry Madan, a science master at Eton College, who based them on Greek mythology, in which Phobos is a companion to the god, Ares.

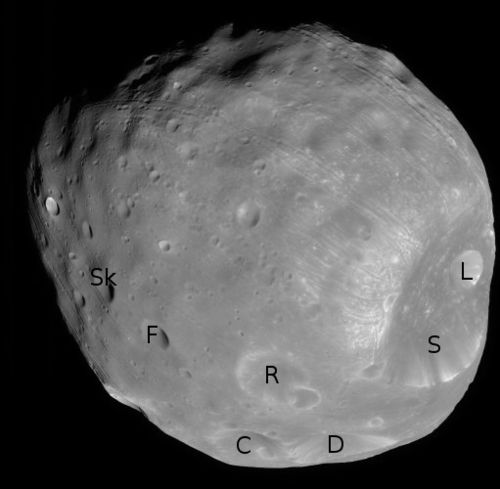

[33] However, in November 2018, following further computational probability analysis, astronomers concluded that the many grooves on Phobos were caused by boulders, ejected from the asteroid impact that created Stickney crater.

[36] Recent images from Mars Global Surveyor indicate that Phobos is covered with a layer of fine-grained regolith at least 100 meters thick; it is hypothesized to have been created by impacts from other bodies, but it is not known how the material stuck to an object with almost no gravity.

[41] Shklovsky based his analysis on estimates of the upper Martian atmosphere's density, and deduced that for the weak braking effect to be able to account for the secular acceleration, Phobos had to be very light—one calculation yielded a hollow iron sphere 16 kilometers (9.9 mi) across but less than 6 centimetres (2.4 in) thick.

[41][42] In a February 1960 letter to the journal Astronautics,[43] Fred Singer, then science advisor to U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, said of Shklovsky's theory: If the satellite is indeed spiraling inward as deduced from astronomical observation, then there is little alternative to the hypothesis that it is hollow and therefore Martian made.

Nevertheless, mapping by the Mars Express probe and subsequent volume calculations do suggest the presence of voids and indicate that it is not a solid chunk of rock but a porous body.

Other modelling suggested since the 1970s support the idea that the grooves are more like "stretch marks" that occur when Phobos gets deformed by tidal forces, but in 2015 when the tidal forces were calculated and used in a new model, the stresses were too weak to fracture a solid moon of that size, unless Phobos is a rubble pile surrounded by a layer of powdery regolith about 100 m (330 ft) thick.

[57][59][inconsistent] Given Phobos' irregular shape and assuming that it is a pile of rubble (specifically a Mohr–Coulomb body), it will eventually break up due to tidal forces when it reaches approximately 2.1 Mars radii.

[65][66] Both moons have very circular orbits which lie almost exactly in Mars' equatorial plane, and hence a capture origin requires a mechanism for circularizing the initially highly eccentric orbit, and adjusting its inclination into the equatorial plane, most probably by a combination of atmospheric drag and tidal forces,[67] although it is not clear that sufficient time is available for this to occur for Deimos.

[63] Geoffrey A. Landis has pointed out that the capture could have occurred if the original body was a binary asteroid that separated under tidal forces.

[69] Another hypothesis is that Mars was once surrounded by many Phobos- and Deimos-sized bodies, perhaps ejected into orbit around it by a collision with a large planetesimal.

Phobos 1 was accidentally shut down by an erroneous command from ground control issued in September 1988 and lost while the craft was still en route.

Phobos 2 arrived at the Mars system in January 1989 and, after transmitting a small amount of data and imagery shortly before beginning its detailed examination of Phobos' surface, the probe abruptly ceased transmission due either to failure of the onboard computer or of the radio transmitter, already operating on backup power.

The Russian Space Agency launched a sample return mission to Phobos in November 2011, called Fobos-Grunt.

[78] A second contributor to this mission was the China National Space Administration, which supplied a surveying satellite called "Yinghuo-1", which would have been released in the orbit of Mars, and a soil-grinding and sieving system for the scientific payload of the Phobos lander.

[79][80] However, after achieving Earth orbit, the Fobos-Grunt probe failed to initiate subsequent burns that would have sent it to Mars.

[81] On 1 July 2020, the Mars orbiter of the Indian Space Research Organisation was able to capture photos of the body from 4,200 km away.

[87] In 2007, the European aerospace subsidiary EADS Astrium was reported to have been developing a mission to Phobos as a technology demonstrator.

A proposed landing site for the PRIME spacecraft is at the "Phobos monolith", a prominent object near Stickney crater.

[89][90][91] The PRIME mission would be composed of an orbiter and lander, and each would carry 4 instruments designed to study various aspects of Phobos' geology.

[92] In 2008, NASA Glenn Research Center began studying a Phobos and Deimos sample return mission that would use solar electric propulsion.

[94] As of January 2013, a new Phobos Surveyor mission is currently under development by a collaboration of Stanford University, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

[100] MMX will land and collect samples from Phobos multiple times, along with conducting Deimos flyby observations and monitoring Mars' climate.

[101][105] Although the mission has been selected for implementation[106][107] and is now beyond proposal stage, formal project approval by JAXA has been postponed following the Hitomi mishap.

The great mass of Phobos means that any forces from space elevator operation would have minimal effect on its orbit.