Natural satellite

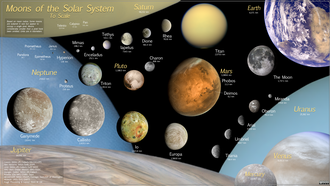

Seven objects commonly considered dwarf planets by astronomers are also known to have natural satellites: Orcus, Pluto, Haumea, Quaoar, Makemake, Gonggong, and Eris.

The first known natural satellite was the Moon, but it was considered a "planet" until Copernicus' introduction of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543.

[citation needed] The first to use the term satellite to describe orbiting bodies was the German astronomer Johannes Kepler in his pamphlet Narratio de Observatis a se quatuor Iouis satellitibus erronibus ("Narration About Four Satellites of Jupiter Observed") in 1610.

He derived the term from the Latin word satelles, meaning "guard", "attendant", or "companion", because the satellites accompanied their primary planet in their journey through the heavens.

[5] The term satellite thus became the normal one for referring to an object orbiting a planet, as it avoided the ambiguity of "moon".

Because of this shift in meaning, the term moon, which had continued to be used in a generic sense in works of popular science and fiction, has regained respectability and is now used interchangeably with natural satellite, even in scientific articles.

Every natural celestial body with an identified orbit around a planet of the Solar System, some as small as a kilometer across, has been considered a moon, though objects a tenth that size within Saturn's rings, which have not been directly observed, have been called moonlets.

The most common[citation needed] dividing line on what is considered a moon rests upon whether the barycentre is below the surface of the larger body, though this is somewhat arbitrary because it depends on distance as well as relative mass.

Triton is another exception; although large and in a close, circular orbit, its motion is retrograde and it is thought to be a captured dwarf planet.

[20][21] Most regular moons (natural satellites following relatively close and prograde orbits with small orbital inclination and eccentricity) in the Solar System are tidally locked to their respective primaries, meaning that the same side of the natural satellite always faces its planet.

This phenomenon comes about through a loss of energy due to tidal forces raised by the planet, slowing the rotation of the satellite until it is negligible.

[26] It has also been proposed that Saturn's moon Iapetus had a satellite in the past; this is one of several hypotheses that have been put forward to account for its equatorial ridge.

[28] Two natural satellites are known to have small companions at both their L4 and L5 Lagrangian points, sixty degrees ahead and behind the body in its orbit.

Of the nineteen known natural satellites in the Solar System that are large enough to be gravitationally rounded, several remain geologically active today.

In the first three cases, the geological activity is powered by the tidal heating resulting from having eccentric orbits close to their giant-planet primaries.

[2] Some 150 additional small bodies have been observed within the rings of Saturn, but only a few were tracked long enough to establish orbits.

Saturn has an additional six mid-sized natural satellites massive enough to have achieved hydrostatic equilibrium, and Uranus has five.

[32] Among the objects generally agreed by astronomers to be dwarf planets, Ceres and Sedna have no known natural satellites.

Similarly in the next size group of nine mid-sized natural satellites, between 1,000 km and 1,600 km across, Titania, Oberon, Rhea, Iapetus, Charon, Ariel, Umbriel, Dione, and Tethys, the smallest, Tethys, has more mass than all smaller natural satellites together.

These are predominantly Greek, except for the Uranian natural satellites, which are named after Shakespearean characters.