Fasciola hepatica

[2] Fasciolosis is currently classified as a plant/food-borne trematode infection, often acquired through eating the parasite's metacercariae encysted on plants.

[3] F. hepatica, which is distributed worldwide, has been known as an important parasite of sheep and cattle for decades and causes significant economic losses in these livestock species, up to £23 million in the UK alone.

[4] Because of its relatively large size and economic importance, it has been the subject of many scientific investigations and may be the best-known of any trematode species.

[5] Fasciola hepatica occurs in the liver and bile ducts of a definitive host and its lifecycle is indirect.

[6] Wild ruminants, such as African buffalo,[7] and other mammals, including humans, can act as definitive hosts as well.

Galba truncatula is the main snail host in Europe, partly in Asia, Africa, and South America.

Lymnaea viator, L. neotropica, Pseudosuccinea columella, and L. cubensis are most common intermediate hosts in Central and South America.

[5][11][8] Several other lymnaeid snails may be naturally or experimentally infected with F. hepatica, but their role in transmission of the fluke is low.

Humans can often acquire these infections through drinking contaminated water and eating freshwater plants such as watercress.

Once in freshwater, the eggs become embryonated, allowing them to hatch as miracidia, which then find a suitable intermediate snail host of the Lymnaeidae family.

This is composed of scleroprotein, and its primary function is to protect the fluke from the destructive digestive system of the host.

The tegument renews its plasma membrane as a protection against compromise and is modified to actively or passively uptake nutrients.

[18][19] The uptake of some compounds (e.g. taurine) makes flukes even more resistant to being killed by the digestive system of the host.

The tegumental cells contain the usual cytoplasmic organelles (mitochondria, Golgi bodies, and endoplasmic reticulum).

Studies have shown that certain parts of the tegument (in this case, the antigen named Teg) can actually suppress the immune response of the mammalian host.

The male and female reproductive organs open up into the same chamber within the body, which is called the genital atrium.

[32] The mitochondrial genome consists of 14462 bp, containing 12 protein-encoding, 2 ribosomal and 22 transfer RNA genes.

[36] In contrast, F. gigantica is generally considered more geographically restricted to the tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, with some overlap between the two species.

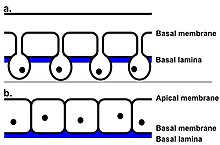

[36] F. hepatica has a tegument that protects it from the enzymes of the host's digestive system, whilst still allowing water to pass through.

[20] Free-swimming larvae have cilia and the cercariae have a muscular tail to help them swim through the aquatic environment and also allow them to reach the plants on which they form a cyst.

The genome contains many polymorphisms, and this represents the potential for the fluke to evolve and rapidly adapt to changes in the environment, such as host availability and drug or vaccine interventions.

In the United Kingdom, F. hepatica frequently causes disease in ruminants, most commonly between March and December.

[41] Therefore, an infection from F. hepatica can make it difficult to detect bovine tuberculosis; this is, of course, a major problem in the farming industry.

[43] The chronic phase occurs when the worms mature in the bile duct, and can cause symptoms of intermittent pain, jaundice, and anemia.

[43] In cattle and sheep, classic signs of fasciolosis include persistent diarrhea, chronic weight loss, anemia, and reduced milk production.

F. hepatica can cause sudden death in both sheep and cattle, due to internal hemorrhaging and liver damage.

[45] Livestock are often treated with flukicides, chemicals toxic to flukes, including bromofenofos,[46][page needed][47] triclabendazole, and bithionol.

One important method is through the strict control over the growth and sales of edible water plants such as watercress.

If a patient has eaten infected liver, and the eggs pass through the body and out via the faeces, a false positive result to the test can occur.

ELISA is available commercially and can detect antihepatica antibodies in serum and milk; new tests intended for use on faecal samples are being developed.