Trichinosis

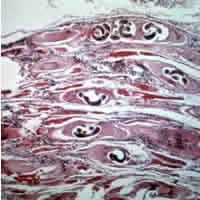

[1] The diagnosis is usually based on symptoms and confirmed by finding specific antibodies in the blood, or larvae on tissue biopsy.

The symptoms vary depending on the phase, species of Trichinella, the quantity of encysted larvae ingested, age, sex, and host immunity.

As the larvae migrate through tissue and vessels, the body's inflammatory response results in edema, muscle pain, fever, and weakness.

[14] They may very rarely cause enough damage to produce serious neurological deficits (such as ataxia or respiratory paralysis) from worms entering the central nervous system (CNS), which is compromised by trichinosis in 10–24% of reported cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, a very rare form of stroke (three or four cases per million annual incidence in adults).

[17] The classical agent is T. spiralis (found worldwide in many carnivorous and omnivorous animals, both domestic and sylvatic (wild),[citation needed] but seven primarily sylvatic species of Trichinella also are now recognized: The typical lifecycle for T. spiralis involves humans, pigs, and rodents.

A pig becomes infected when it eats infectious cysts in raw meat, often porcine carrion or a rat (sylvatic cycle).

[12] Adult worms can only reproduce for a limited time because the immune system eventually expels them from the small intestine.

[16] The case definition for trichinosis at the European Center for Disease Control states, "at least three of the following six: fever, muscle soreness and pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, facial edema, eosinophilia, and subconjunctival, subungual, and retinal hemorrhages.

[16] A similar protocol exists in the United States, in the USDA guidelines for farms and slaughterhouse responsibilities in inspecting pork.

[25] Public education about the dangers of consuming raw and undercooked meat, especially pork, may reduce infection rates.

[33] The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is responsible for the regulations concerning the importation of swine from foreign countries.

[16] Early administration of anthelmintics, such as mebendazole or albendazole,[35] decreases the likelihood of larval encystation, particularly if given within three days of infection.

[36] These drugs prevent newly hatched larvae from developing, but should not be given to pregnant women or children under two years of age.

[12] Medical references from the 1940s described no specific treatment for trichinosis at the time, but intravenous injection of calcium salts was found to be useful in managing symptoms related to severe toxemia from the infection.

[43][44] The second outbreak in France was associated with pork sausages from Corsica, which were eaten raw, affecting 14 people in total.

However, a trichinosis surveillance conducted between 1997 and 2001 showed a higher percentage of cases caused by consumption of wild game (the sylvatic transmission cycle).

This is thought to be due to the Federal Swine Health Protection Act (Public Law 96-468) that was passed by Congress in 1980.

Additionally, other requirements were put in place, such as rodent control, limiting commercial swine contact with wildlife, maintaining good hygiene, and removing dead pigs from pens immediately.

[citation needed] The kashrut and halal dietary laws of Judaism and Islam prohibit eating pork.

[49] The disappearance of the pathogen from domestic pigs has led to a relaxation of legislation and control efforts by veterinary public health systems.

[50] Major sociopolitical changes can produce conditions that favor the resurgence of Trichinella infections in swine and, consequently, in humans.

For instance, "the overthrow of the social and political structures in the 1990s" in Romania led to an increase in the incidence rate of trichinosis.

In 1835, James Paget, a first-year medical student, first observed the larval form of T. spiralis, while witnessing an autopsy at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London.

Although Paget is most likely the first person to have noticed and recorded these findings, the parasite was named and published in a report by his professor, Richard Owen, who is now credited for the discovery of the T. spiralis larval form.

Its mission is to exchange information on the epidemiology, biology, pathophysiology, immunology, and clinical aspects of trichinosis in humans and animals.

Since the creation of the ICT, its members (more than 110 from 46 countries) have regularly gathered and worked together during meetings held every four years: the International Conference on Trichinellosis.