Iron gall ink

Fermentation or hydrolysis of the extract releases glucose and gallic acid, which yields a darker purple-black ink, due to the formation of iron gallate.

After filtering, the resulting pale-grey solution had a binder added to it (most commonly gum arabic) and was used to write on paper or parchment.

The resulting marks would adhere firmly to the parchment or vellum, and (unlike india ink or other formulas) could not be erased by rubbing or washing.

[3] The darkening process of the ink is due to the oxidation of the iron ions from ferrous (Fe2+) to ferric (Fe3+) state by atmospheric oxygen.

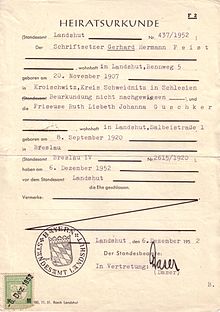

[8] Laws were enacted in Great Britain and France specifying the content of iron gall ink for all royal and legal records to ensure permanence in this time period as well.

The permanence and water-resistance of the iron and gall-nut formula made it the standard writing ink in Europe for over 1,400 years, and in America after European colonisation.

[citation needed] Today, iron gall ink is manufactured by a small number of companies and used by fountain pen enthusiasts and artists, but has fewer administrative applications.

While its use is waning globally, it is still required (along with Klaf) by Jewish Halakha for various religious documents, such as a Get, a Ketubah, Mezuzahs, and Torah Scrolls.

In general, the darkening process will progress more quickly and visibly on papers containing relatively high bleaching agent residues.

[15][16][17][18] In Germany the use of special blue or black urkunden- oder dokumentenechte Tinte or documentary use permanent inks is required in notariellen Urkunden (Civil law notary legal instruments).

In India, the IS 220 (1988): Fountain Pen Ink – Ferro-gallo Tannate (0.1 percent iron content) Third Revision standard, which was reaffirmed in 2010, is in use.

IS 220 prescribes the requirements and the methods of sampling and tests for ferrogallo tannate fountain pen inks containing not less than 0.1 percent of iron.